Read Time 5 minutes

Looking back at The Black Audio Film Collective

As John Akomfrah prepares to represent the United Kingdom at the 2024 Venice Biennale, now is a pertinent time to revisit this experimental collective’s work, history and impact, and look for clues as to what we might expect.

The 1980s was a time of disparate polarities in the United Kingdom. Collective Labour movements across the country were losing steam whilst Margaret Thatcher’s right-wing coalition fervently worked at establishing their neoliberal project, the detritus of which can be witnessed across the U.K. today. Amid this socio-economic milieu, the ACCTT workshop declaration––an agreement between various arts organisations––provided funding and national broadcasting for some of the most progressive and challenging works to emerge from the British film industry. Through funds secured by way of the declaration, a group of seven artists and thinkers of disparate practices, under the moniker ‘The Black Audio Film Collective’ (BAFC), created over a dozen works focused on Africa and its diaspora, a segment of the population rarely depicted on our own terms.

BAFC formed at Portsmouth Polytechnic in 1982, later relocating to a warehouse in Dalston, London. Its members included John Akomfrah, Edward George, Avril Johnson, Reece Auguiste, Lina Gopaul, Claire Joseph and Trevor Mathison. Bound by a communal aptitude for cross-cultural referencing, they tinkered, programmed events, and created moving image experiments. The fingerprints of a multitude of artists from science-fiction writer Octavia Butler to French film essayist Chris Marker can be seen on their work, contouring the collective with a unique voice and style. Edward George’s 1998 Tupac documentary Gangsta Gangsta [un]surprisingly begins with a quote from 20th-century German philosopher Walter Benjamin: “The destructive character is always cheerful. The destructive character does not think of the future. He sees nothing permanent. He always positions himself at the crossroads because he sees ways everywhere”. The invocation of Benjamin’s work here, which often plunged into the ways in which mass media and technology shaped modern society, provides the audience with a critical lens to examine Tupac’s story. This ability to meld together pop culture and academia allowed the collective’s work to traverse new terrain and grapple with conceptions of truth, in the context of documentary work, history and the quotidian, whilst still remaining accessible.

Gangsta Gangsta was the final film produced by the BAFC before their dissolution in 1998. It’s unclear what led to the group’s end but the election of Tony Blair’s Labour government in ‘97 and the introduction of policies aimed at improving conditions for marginalised communities potentially pushed some members of the collective to feel their work was no longer as urgent. These changes to the political and cultural landscape in Britain compounded with issues around funding for their projects may have bred fertile grounds for disbandment.

In the years following, John Akomfrah and Lina Gopaul co-founded Smoking Dogs Films, producing award-winning documentaries and features. Edward George launched a multitude of projects as a solo artist, including an experimental radio show titled ‘The Strangeness of Dub’ and Trevor Mathison has continued to work as a composer for film and television. Prior to their disbandment, BAFC’s active confrontations with Blackness as cultural material played a crucial role in further legitimising Black-British identities. Their emphasis on maintaining a structure of collective authorship and active desire to challenge dominant narratives of British history through off-kilter formal and stylistic storytelling choices, as opposed to the prominent soap box style activist art of the time, set them apart in both the mainstream filmmaking and experimental art worlds.

Films you should know by the BAFC:

TWILIGHT CITY, Dir. Reece Auguiste, [1989]

Twilight City is a reflection on the effects of gentrification on 1980s London, told through a fictional letter by Olivia, a researcher based in the city, to her mother in Dominica. In typical BAFC form, the film features commentary from a stellar cast of thinkers and artists, most notably a young Paul Gilroy, author of ‘The Black Atlantic’. The commentators provide insights into the politics of the time through accounts of their own experiences while Olivia’s letter humanises the story, bestowing it with emotional gravitas. This powerful film still resonates today as we continue to witness the effects of gentrification on working-class communities in London.

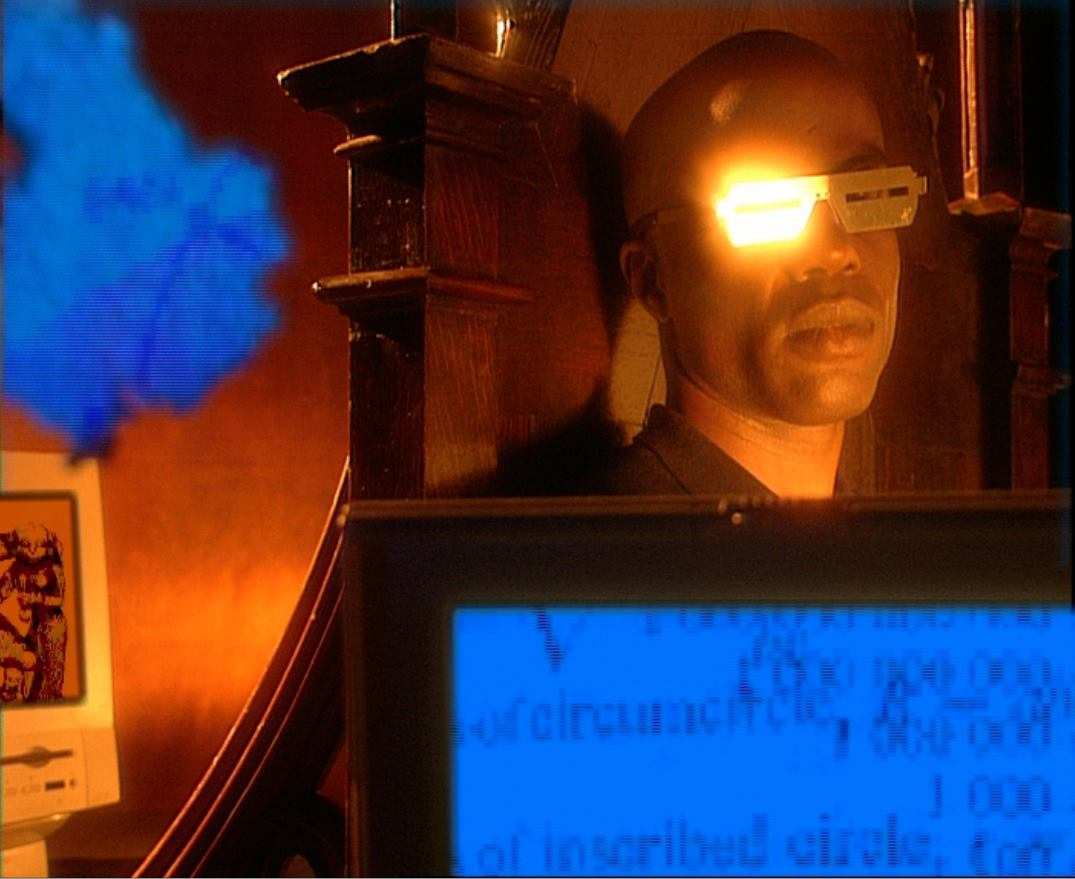

LAST ANGEL OF HISTORY, Dir. John Akomfrah, [1996]

The Last Angel of History is often credited as the first film to explore afro-futurism. Inspired by French filmmaker Chris Marker’s 1962 film ‘La Jetée’ and Walter Benjamin’s analysis of Swiss-German Artist Paul Klee’s ‘Angelus Novus’, the BAFC created this docu-fiction. Written and presented by Edward George, The Last Angel of History explores afro-futurism through a spatial and temporal nomad named ‘The Data Thief’. The Data Thief traverses through time and space via technological means, collecting information on Black histories and speculative futures. Scavenging through the detritus of time, our nomad makes correlations between Black music and science fiction. Conversations with writer Greg Tate, theorist Kodwo Eshun, jazz composer Sun-Ra, Science fiction writer Octavia Butler and electro-funk artist George Clinton provide the foundations for the film. The cast tackles ancestral memory, alienation, inherited trauma and the middle passage.

HANDSWORTH SONGS, Dir. John Akomfrah, [1986]

Handsworth Songs is a reaction to the coverage of various riots across England by mainstream media outlets in 1985, paying particular attention to the most notorious of them all, the Handsworth riots. Implementing BAFC’s distinct cinematic language of newspaper reels, still images, on-location footage and sonic assemblage, the documentary chronicles the aftermath of various police killings. It serves as a meditation on the socio-economic landscape that gave way to the string of civil disturbances. Handsworth Songs set out to begin a conversation around what it meant to be young Black and British in the 1980s in hopes of reconfiguring the public’s understanding of the unrest.

END

All images courtesy of the Black Audio Film Collective.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?