Read Time 8 minutes

Historical heroines: Corinne Day & the search for reality

The tropes of realism in contemporary fashion photography can largely be credited as having come from the aesthetic signatures of the late Corinne Day, whose work in the 1990s signalled a new direction for image making. All these years later, we’re still under her spell.

The much-parroted phrase ‘heroin chic’ was popularised by Bill Clinton, he of sucked-dick and presidential fame, in the late 1990s to describe the type of grubby glamour that was widespread in the popular fashion press of the time. There was a genuine fear that the fashion photography of the late twentieth century was impactful in a way that would set young people on a course for self-destruction, a fear that was pervasive enough to inspire broadsheet op-eds and treatise from POTUS. Amidst all this moralising, what was less clear was what was the cause and what was the effect. Did people want to be skinny [and use Class A drugs to help them get there, as the commentators hypothesised] because they saw skinny people in the pages of Vogue, or were the skinny, disenchanted people pictured in Vogue there because they spoke to the reality of how young people actually looked? At the centre of the discourse was the work of one English woman. In the course of three years spent writing this humble column I don’t think I’ve touched on an artist who is responsible for influencing a massive cultural vibe shift quite like this. Certainly the work of previous historical heroines had a profound effect on other artists, which would then gradually filter through to everyday culture, but there hasn’t been one whose singular artistic motifs actually changed the zeitgeist––transcending industry and influencing those inclined to resist influence––quite like Corinne Day.

Such is the power of fashion and fashion photography – ostensible frivolity but in actual fact loaded with meaning, with stories, and with real-life application. Unlike other photographic genres, fashion is concerned with the essentials of what we desire to be, or in Corinne Day’s case arguably, who we actually are, as told through raggedy jumpers and girlish knickers.

Corinne Day’s [1965-2010] fashion photographs were unlike anything which had been seen before. Through the 80s––the decade that saw the invention of the supermodel––the pages of magazines were filled with images of polished women, seen through the eyes of the mostly male photographers, powerful yet sexualised, blow dried, high net worth, unattainable, unknowable, improbable. Then, the 90s arrived, along with Corinne, a former model herself who brought such a fresh new approach to image-making that it changed the game completely. There were others of course: David Sims, Glen Luchford, and Nigel Shafran [not to mention Corinne’s regular collaborators, the stylist Melanie Ward and fledgling model Kate Moss], but all of these figures have had the good fortune to live for far longer than Corinne, who died young at only 48, and are therefore not so easily associated with the visual culture of this one specific time and place only, having had countless opportunities to evolve and reinvent.

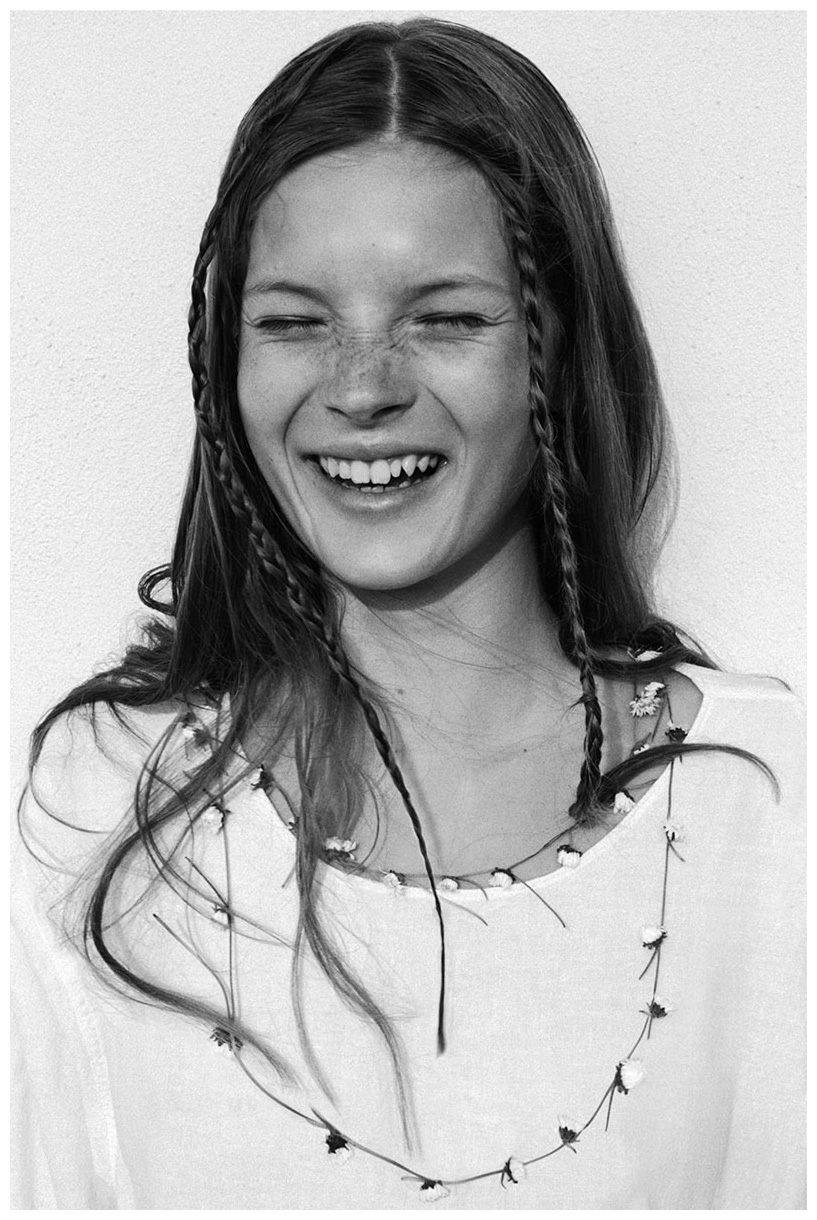

Corinne’s photos of Kate Moss for The Face in 1990 ushered in a new era of aesthetics, of style, of beauty, and of fashion. The lo-fi, raw, anti-glamour shots signalled a move towards a more understated, minimalist approach to style, championing realness––contentious though it was––and an effortless cool. The teenage Kate was scrawny and boyish, short by model standards, with bow legs and lank hair and the most beguiling face. Kate Moss, who would become one of the most influential models of all time, owes some of her early success to Corinne, whose taste for girls with eye bags and chewed fingernails was antithetical to the shininess and label obsession of the preceding decade. Soon enough, the counter-cultural, rebellious style was picked up by the glossies and Corinne was catapulted to stardom. Where the glossies go, the rest of the world follows. When the photographs hit the mainstream critics accused Corinne of glamorising hard drugs, eating disorders, suicide, even paedophilia. In fact, there isn’t much in the way of glamour in most of the work, and these criticisms weren’t representative of what the photographs actually showed, but bad faith interpretations.

There were, as with any cultural moment, a few stars that had to align in order to allow Corinne Day’s style of anti-fashion fashion photography to take off, and one of these was a recession. Economic depression and the fashion industry are always linked, and in this case it precipitated a nihilistic aesthetic that seemed to reflect the mood and habits of its audience, as well as being more palatable to their budget. In 1992 the critic Sarah Mower referred to Corinne as the ultimate ‘recessionary photographer’. Kate Moss described it as ‘skanky.’ Corinne herself labelled the style she espoused as ‘Tramp’.

That’s not to say though that these photographs were necessarily honest. Kate Moss may have lived in a sparsely furnished bedsit in those early years, but her rise was meteoric and she became very rich very quickly. Likewise for Corinne herself, whose Soho apartment was quite artfully dishevelled in the same way as her photographs. The ‘natural’ look worked because the girls who were chosen for their so-called imperfections and personalities were also stunning [this idea of Kate Moss being flawed because she was a few inches shorter than most runway models is not a flaw that the majority of women can relate to, much as she was seen as this girl-next-door type, she was the most breathtaking girl-next-door you could possibly imagine]. As fame and fortune grew, eventually the mousyness had to be exaggerated and grime applied manually. What may have begun as naivety and a genuine reflection of reality soon became a contrived formula that could be replicated ad infinitum.

Today the notion of reality is becoming ever more nebulous, but there are image makers who are still attempting to capture it, whatever it is. When they do, it will inevitably look something like a Corinne Day photograph, with that deliberate application of grit, or mundanity. Reality, in this context, is a manufactured artifice, a tromp-l’oeil. We may have moved away from heroin chic [and then back again … round and round the cycle goes], but its markers are still with us. Fashion photography that doesn’t really look like fashion photography. Couture with a pebbledash backdrop, luxury brands cavorting in greasy spoons. Suburbia, ugly carpets, DIY looks, flaking paintwork, littered pavements, English beach resorts, untidy cables, smudged eyeliner, box-dye and wonky teeth. The trappings of working class Britain stamped with a Burberry logo. Writing about Corinne Day under the ‘historical’ moniker feels slightly egregious for a few reasons, not least how recently this all happened, but also because it’s not over yet. She may be gone but her legacy lives, as the woman who invented reality.

END

All photographs courtesy of The Corinne Day Archives.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?