Read Time 11 minutes

Historical Heroines: Vivian Maier’s elusive story

Vivian Maier’s extraordinary photographs throw up far more questions than they answer.

Her story is full of loose threads and unfinished paragraphs, yes, but bigger than Vivian herself is this spectre of a thing which her art sits perpetually in the shadow of: the question of privacy.

The story goes like this.

Vivian Maier was born in New York City in 1926, of French and Austrian extraction, and spent parts of her childhood in both Europe and the US. When she grew up she became a live-in nanny in well-off homes and spent her life living as part of other peoples’ families, raising their children, travelling with them and living where they lived, be it suburbs or cities. She was an observant woman usually to be found with more than one camera hanging around her neck, a bit eccentric, a paranoid loner who was admired by her charges, well-travelled and cultured to an unusual extent for someone in such a domestic job. This could have been the full story, but, only a few years before she died in 2009, Vivian was failing to keep up with payments on several storage lockers––kept to home her innumerable hoarded possessions––which were then auctioned off, the contents scattered.

Amongst this collection of bits and bobs, [newspapers and art books aplenty, whozits and whatzits galore], were upwards of 100,000 photo negatives, taken by Vivian herself, which were discovered to be REALLY rather good. And so, this woman who was born some 80 years previous, into Depression era, pre-www. America, became an internet sensation, almost overnight.

Is this what she wanted?

The opinions differ and the answer is, of course, inconclusive. On the one hand it has been noted by John Maloof, the man responsible for ‘discovering’, researching and promoting Vivian Maier, that at some point in her lifetime she did begin a process of speculatively putting her work out there, in the sense that she sent her work to a printer with very specific instructions as to the finish. What her intentions were with regards the prints is unclear, but it is not true to say that she never shared her work with anyone. That being said, the act of sending some scans to a printer is just a baby-step, compared to the gargantuan leap taken by Maloof in platforming Maier in the way he has.

We’re being surveilled and recorded as a matter of course, in most public spaces, so does knowing that constitute a tacit consent to then being photographed or recorded by a stranger with a camera? Is it okay to take a picture of someone as long as it’s not mean-spirited, if you’re not laughing at them? Is it okay to post a photo of a stranger on the internet if I’m being complimentary? Should parents be allowed to post photographs of their kids online before the child is able to consent? If I’m in someone’s picture and I ask them to delete it do they have the right to refuse? Is my image less worthy of protection than someone’s intellectual property? Why? Does any of this even matter if it’s Art?

Vivian Maier died three years after the birth of Twitter, and as far as we know she didn’t use it in that time, so she was free from the discourse of the Chronically Online. But now the internet is the forum in which her artwork is largely being viewed, so it is, I think, okay to at least consider this discourse in relation to her work.

Those who knew Vivian Maier describe her as intensely private. They remember the presence of the camera[s] round the neck, they remember being in the frame of some of her shots, but they never seem to have connected the dots between this and the body of work she ended up having. They didn’t think of her as an artist, or even a photographer. And it’s fair to conclude that this was by design. She didn’t want them to know. She knew that her photos were excellent, it wasn’t modesty, just that the act of spotting something interesting and clicking the shutter was more important to her than the end product. It was for herself only, a momentary thrill in a life of few thrills.

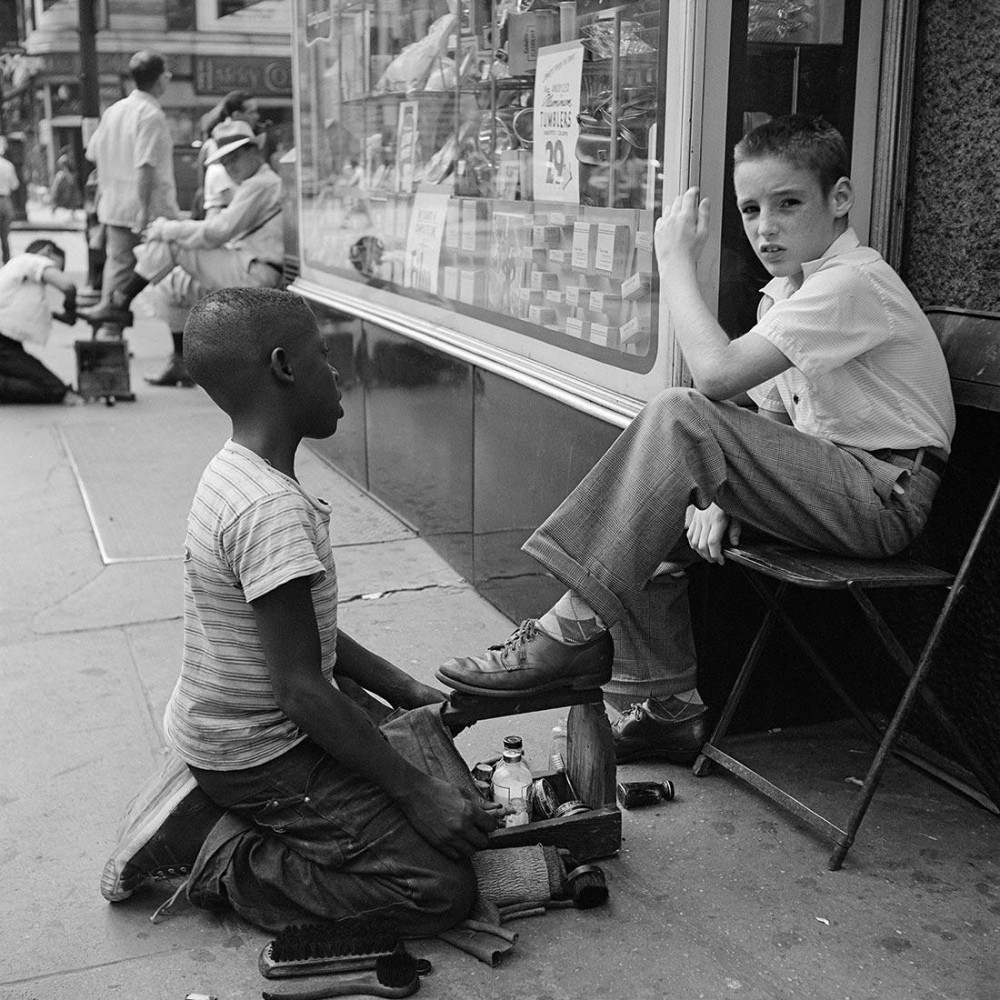

There’s a second chapter to this question of privacy and it pertains to Vivian as the exploiter, not just the exploited. As ubiquitous as it is, photography is still relatively young and misunderstood, its powers and uses slightly frightening, its legalities nebulous. It’s a post-internet problem I’m sure. We are in an age of camera as invasive instrument, one embroiled in conversations about consent.

Does: photography + internet = fear?

Those who knew Vivian Maier describe her as intensely private. They remember the presence of the camera[s] round the neck, they remember being in the frame of some of her shots, but they never seem to have connected the dots between this and the body of work she ended up having. They didn’t think of her as an artist, or even a photographer. And it’s fair to conclude that this was by design. She didn’t want them to know. She knew that her photos were excellent, it wasn’t modesty, just that the act of spotting something interesting and clicking the shutter was more important to her than the end product. It was for herself only, a momentary thrill in a life of few thrills.

There’s a second chapter to this question of privacy and it pertains to Vivian as the exploiter, not just the exploited. As ubiquitous as it is, photography is still relatively young and misunderstood, its powers and uses slightly frightening, its legalities nebulous. It’s a post-internet problem I’m sure. We are in an age of camera as invasive instrument, one embroiled in conversations about consent.

Does: photography + internet = fear?

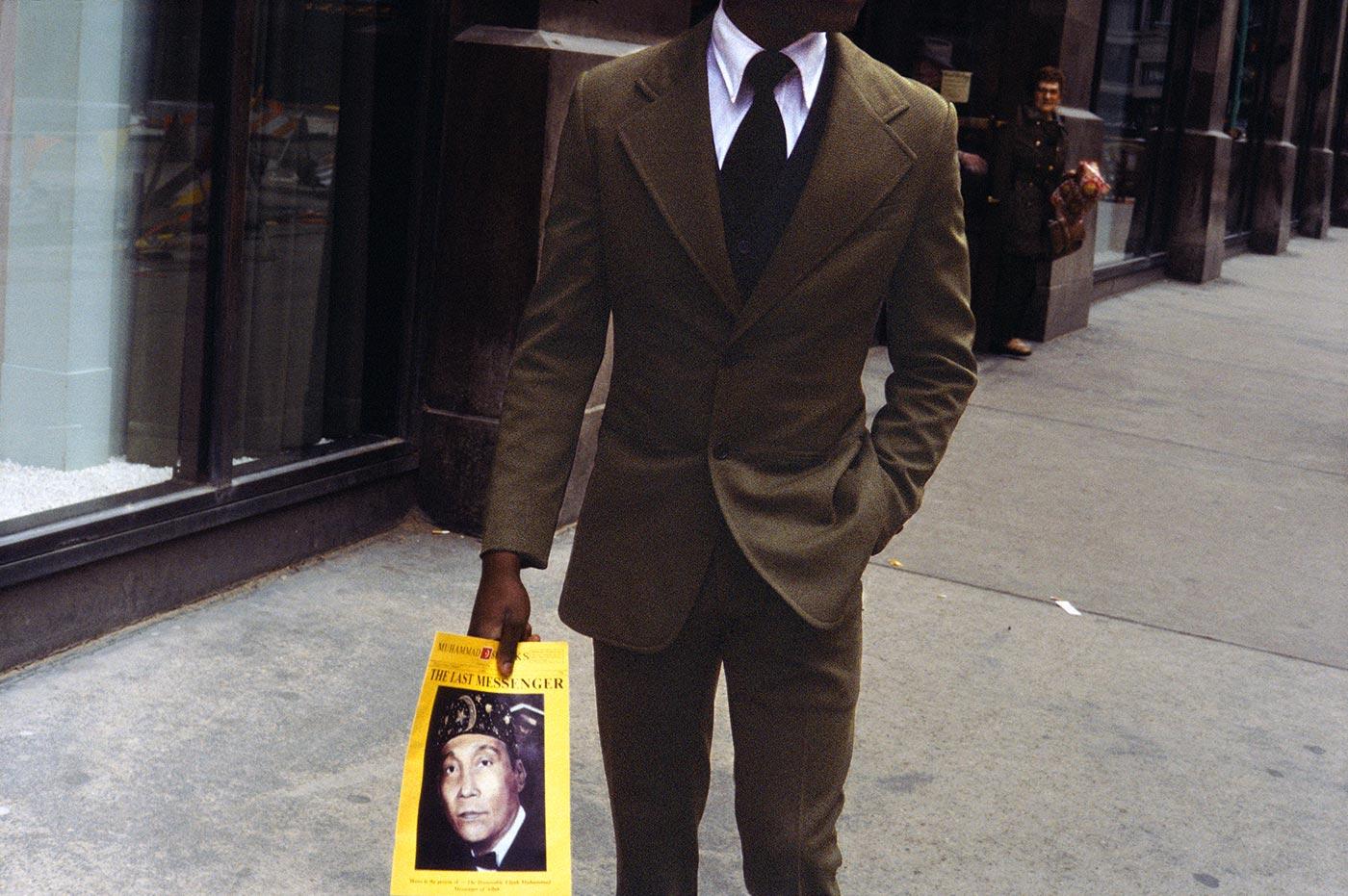

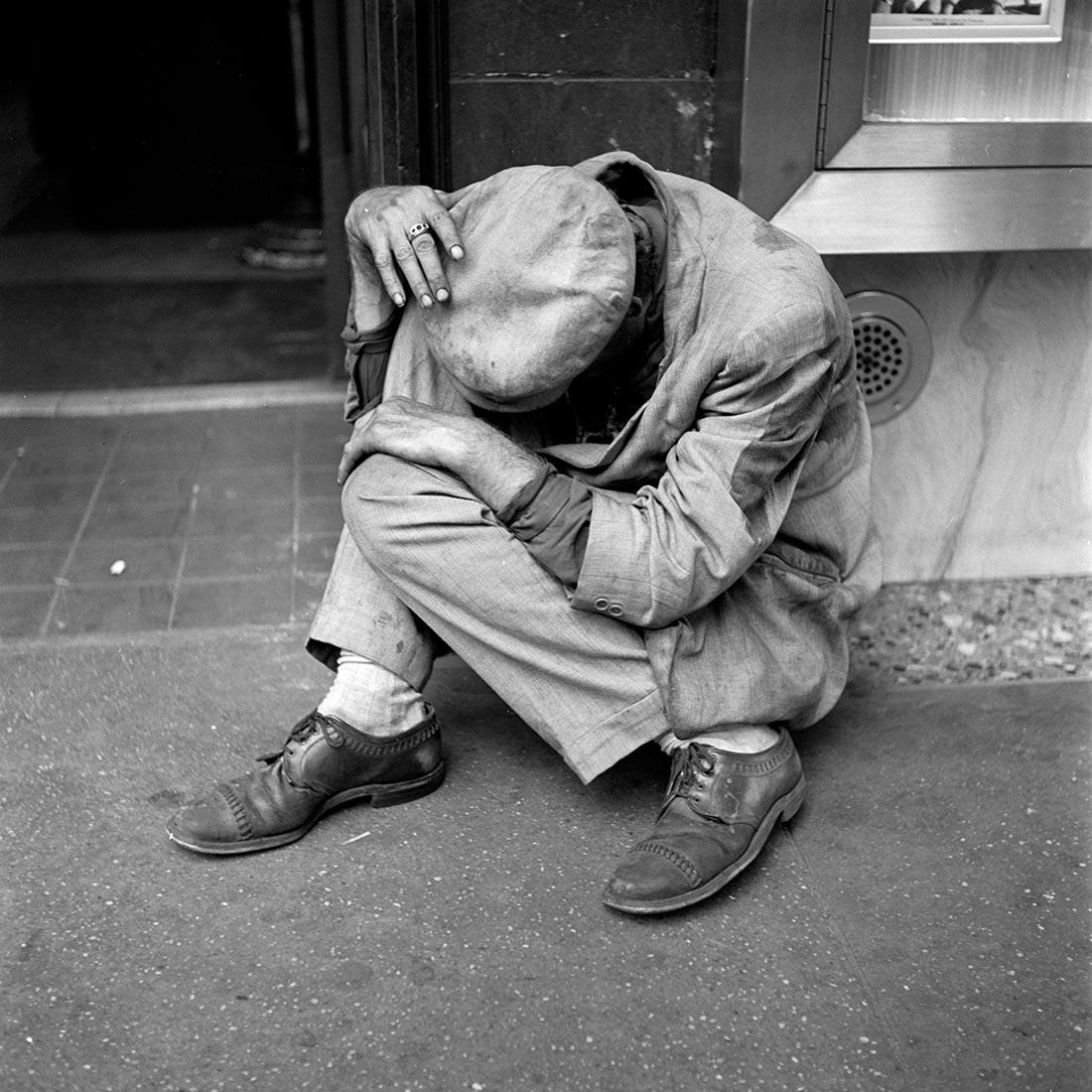

The twin-lens Rolleiflex which Vivian Maier most often used had the useful quality of discretion; not that the camera itself is especially small in form, but the viewfinder is positioned on the top and seen from above, so the camera can be held and used at about waist-height – meaning that one can capture a person unawares very easily. Vivian utilised this quality often. Scores of people she recorded over half a century would have never even known that the woman in the heavy boots and floppy felt hat that they may have not even noticed, had noticed them; their unique oddness, their interesting gesture, their tragic or absurd appearance, their degradation or their joy, their very existence in a moment in time. But she did. She noticed, she captured, she kept a record, and now the record is public, and we see them too. Those people just going about their lives. The children whose parents had trusted Vivian to care for them were a fixture of the photographs she made. Were they allowed to have a say in it? Does it matter? If someone surreptitiously took my photo would I mind? Would I mind if that person was posthumously labelled an artistic genius and put on international display? What if my picture was one of the ones they displayed?

I am asking these questions because I am genuinely confounded by them, not because I think Vivian Maier has all the answers. I really can’t be sure where I sit with regards photography and exploitation, and surely there has to be some scrutiny of artists who, it could be said, tread a similar path to paparazzi, or even those who simply embarrass people who already feel marginalised, not to make a quick buck but just for the thrill of taking the photo. Remember, Vivian Maier probably didn’t consider herself to be an artist, and certainly nobody else did until after the fact, so the ‘but it’s Art!’ defence is, perhaps, moot.

f you think me unfair for applying twenty-first century ethical questions to a twentieth century figure, maybe you’re right. However, I think there is something about Vivian Maier that feels ahead of her time [even if the subject of her photographs is so deeply rooted in time and place].

Firstly, the volume of her work, all of it unpublished in her lifetime. 100,000 photographs was more than most amateurs would accumulate at the time she was working, but nowadays it doesn’t seem so many. My phone––my main camera as a non-photographer––has around 34,000 photos stored on it, which is pretty modest, plus I’m only 29 so there will be plenty more photos to come and many already lost. So there is a relatability to her. Not a professional artist, but a chick with a day job and a good eye.

Secondly, you can see Vivian’s influence in things which feel distinctly modern. Contemporary photographers like Rosie Marks or even Bruce Gilden or Martin Parr, capture scenes and people which you can imagine Vivian capturing too – albeit in a different format and very different aesthetic. And if you follow any given art director on Instagram you’ll see pictures of the minutiae of everyday life and its juxtapositions: the tiny gestures, the mundane, the imperfectness, the mess, the absurdity, plus a peppering of artful selfies, all of which Vivian would no doubt approve. These are the people steering modern culture and taste. The things we are into in 2023 are the same things that Vivian Maier was into in the 1950s, which is pretty cool of her.

f you think me unfair for applying twenty-first century ethical questions to a twentieth century figure, maybe you’re right. However, I think there is something about Vivian Maier that feels ahead of her time [even if the subject of her photographs is so deeply rooted in time and place].

Firstly, the volume of her work, all of it unpublished in her lifetime. 100,000 photographs was more than most amateurs would accumulate at the time she was working, but nowadays it doesn’t seem so many. My phone––my main camera as a non-photographer––has around 34,000 photos stored on it, which is pretty modest, plus I’m only 29 so there will be plenty more photos to come and many already lost. So there is a relatability to her. Not a professional artist, but a chick with a day job and a good eye.

Secondly, you can see Vivian’s influence in things which feel distinctly modern. Contemporary photographers like Rosie Marks or even Bruce Gilden or Martin Parr, capture scenes and people which you can imagine Vivian capturing too – albeit in a different format and very different aesthetic. And if you follow any given art director on Instagram you’ll see pictures of the minutiae of everyday life and its juxtapositions: the tiny gestures, the mundane, the imperfectness, the mess, the absurdity, plus a peppering of artful selfies, all of which Vivian would no doubt approve. These are the people steering modern culture and taste. The things we are into in 2023 are the same things that Vivian Maier was into in the 1950s, which is pretty cool of her.

But, poor Vivian. In her final years she became something like many of the people she photographed; tragic. The sad, lonely character that most neighbourhoods have. Hunting through garbage, cold food from a can. She died, as she lived, in the care of strangers. Now her talent means she is hardly able to rest in peace. What an afterlife she is having, with so much put upon her shoulders: so much unwanted limelight and invasive attention. A tortured soul it seems, in both life and in death.

Last question: Do we give up our right to privacy when we die?

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?