Read Time 10 minutes

The Images That Made Me

HOW MUCH DOES IMAGERY HELP SHAPE THE PERSON WE BECOME? WHICH PHOTOGRAPHS ARE THE ONES WE REMEMBER AS CHANGING US IN SOME WAY––CREATIVELY, PERSONALLY, PROFESSIONALLY––OR SIMPLY AS MARKING THE PASSAGE OF TIME?

WE ASK INDUSTRY LEADERS, ARTISTS AND EXPERTS IN VISUAL CULTURE TO TALK US THROUGH THE FIVE PHOTOGRAPHS THAT HAVE BROUGHT THEM TO WHERE THEY ARE NOW. THINK DESERT ISLAND DISCS, BUT MAKE IT ART.

We have a running joke in Team Darklight: Drink every time one of us mentions Emily Keegin’s Instagram. Her takes––she would call them rants––on photographs in the cultural zeitgeist are a constant source of stimulation, education and delight. Her examination of the provenance of common visual tropes, her dissection of trends and measured judgements on an artists’ successes and failures, the sharpness of her eyes. Could listen to it all day honestly.

With this thought in mind you may notice that this edition of The Images That Made Me is a little … different than usual. Photographs really seem to speak to Emily and she speaks back to them, back and forth back and forth back and forth. She describes photography as ‘a deeply critical practice, one … intrinsically linked to larger social and historical trends.’ But it’s evidently emotional too. Poetic even. Every thought and event and breath is marked by a corresponding image. How could we limit this to five photos only? So we broke the rules, said fuck it to the format, and let Emily talk.

HERE ARE THE IMAGES THAT MADE EMILY.

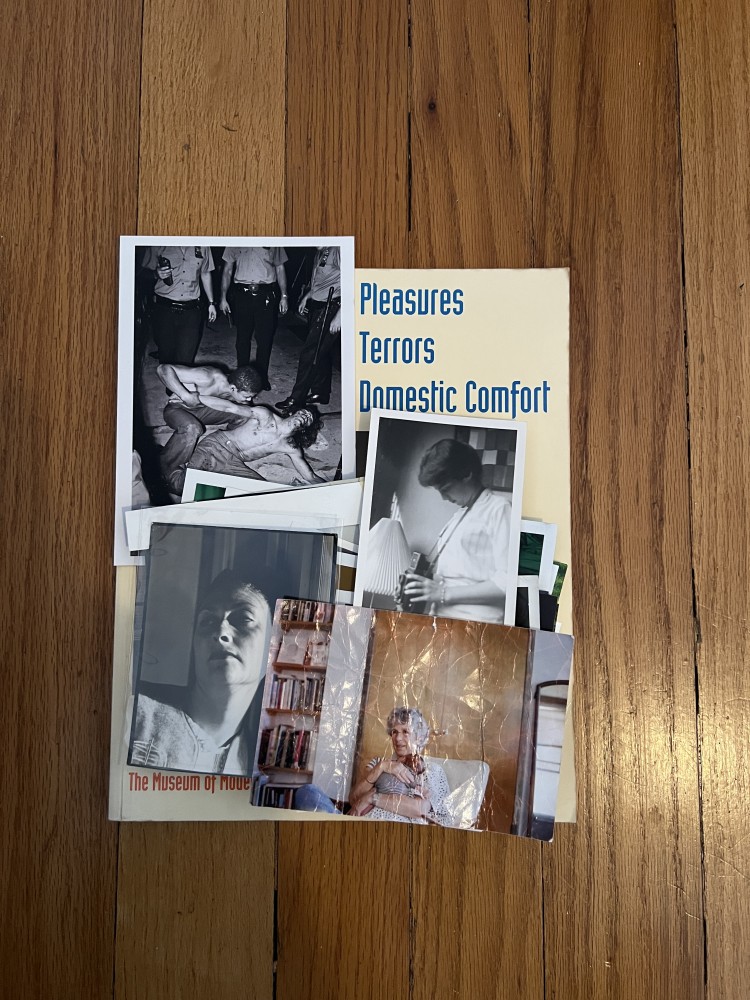

[COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS FROM MY GO-BAG DUMPED ON A BOOK ON MY FLOOR]

– CLOCKWISE FROM TOP RIGHT:

MY MOTHER AGE 13 WITH HER CAMERA; MY MOTHER HOLDING MY DAUGHTER FOR THE FIRST TIME,

[WHEN MY DAUGHTER WAS TWO SHE LIKED TO CARRY THIS PICTURE IN HER POCKET AND SLEEP NEXT TO IT AT NIGHT]; MY GRANDMOTHER, JOSEPHINE; JILL FREEDMAN FIGHT TO THE DEATH, PRINT FROM A PRINT SALE IN 2016

2019 was a bad year for fires in Northern California. One night my husband and I made a go-bag in case the winds changed, and we had to run. We threw some clothes, bottles of water, and our passports in a backpack. On top we placed a small box of photographs.

I like to watch a reality television show called “Alone”. In it, contestants try to survive in the wilderness for 100 days with limited supplies and no human contact. The show allows contestants to bring 30 items from an approved list of essentials… the list is excruciatingly short [you’re allowed only three pairs of underpants, a single t-shirt etc.]. But at the bottom of the list, the very last item listed is one personal photo.

Pictures from home are important. We can’t survive without them.

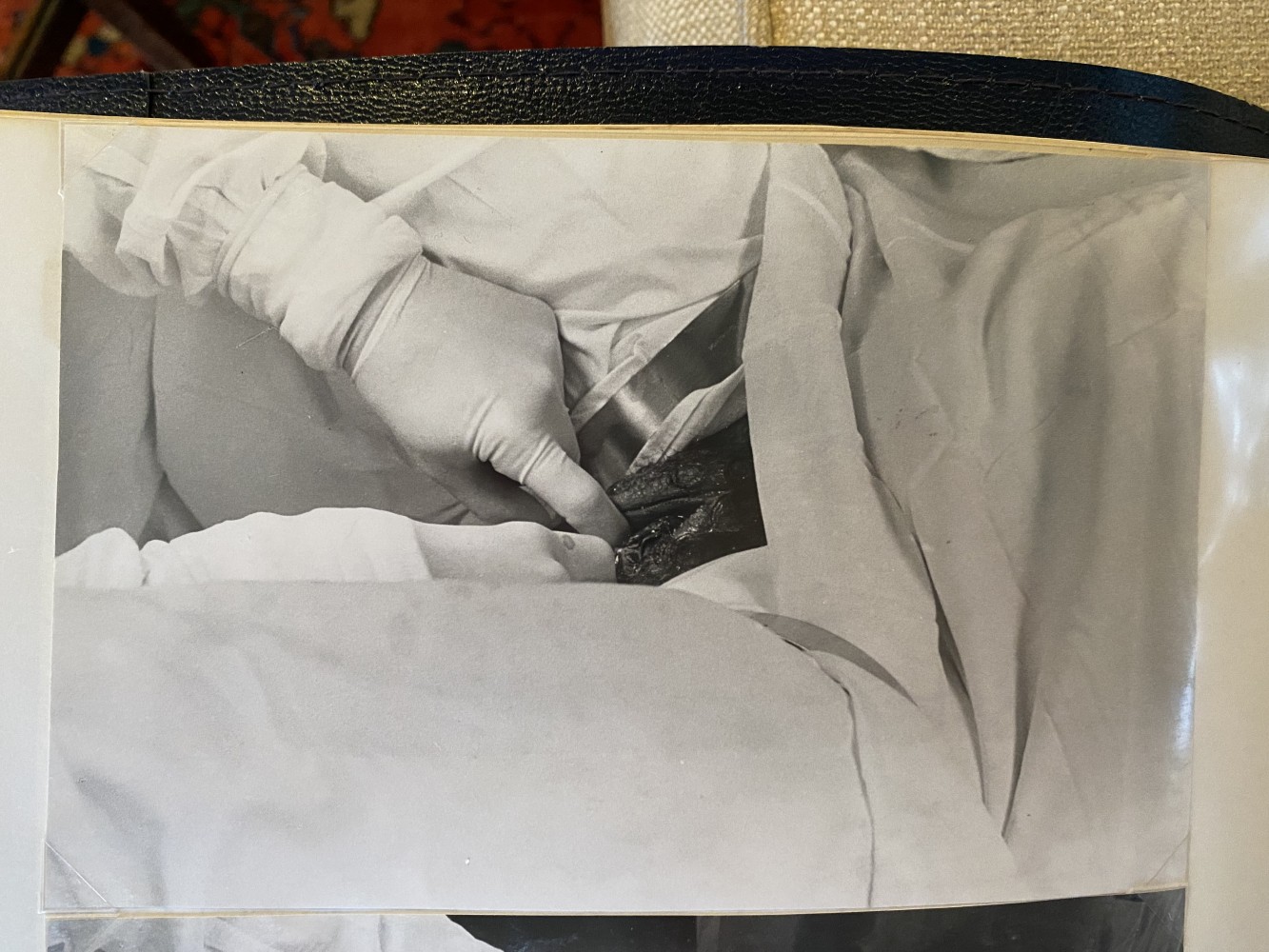

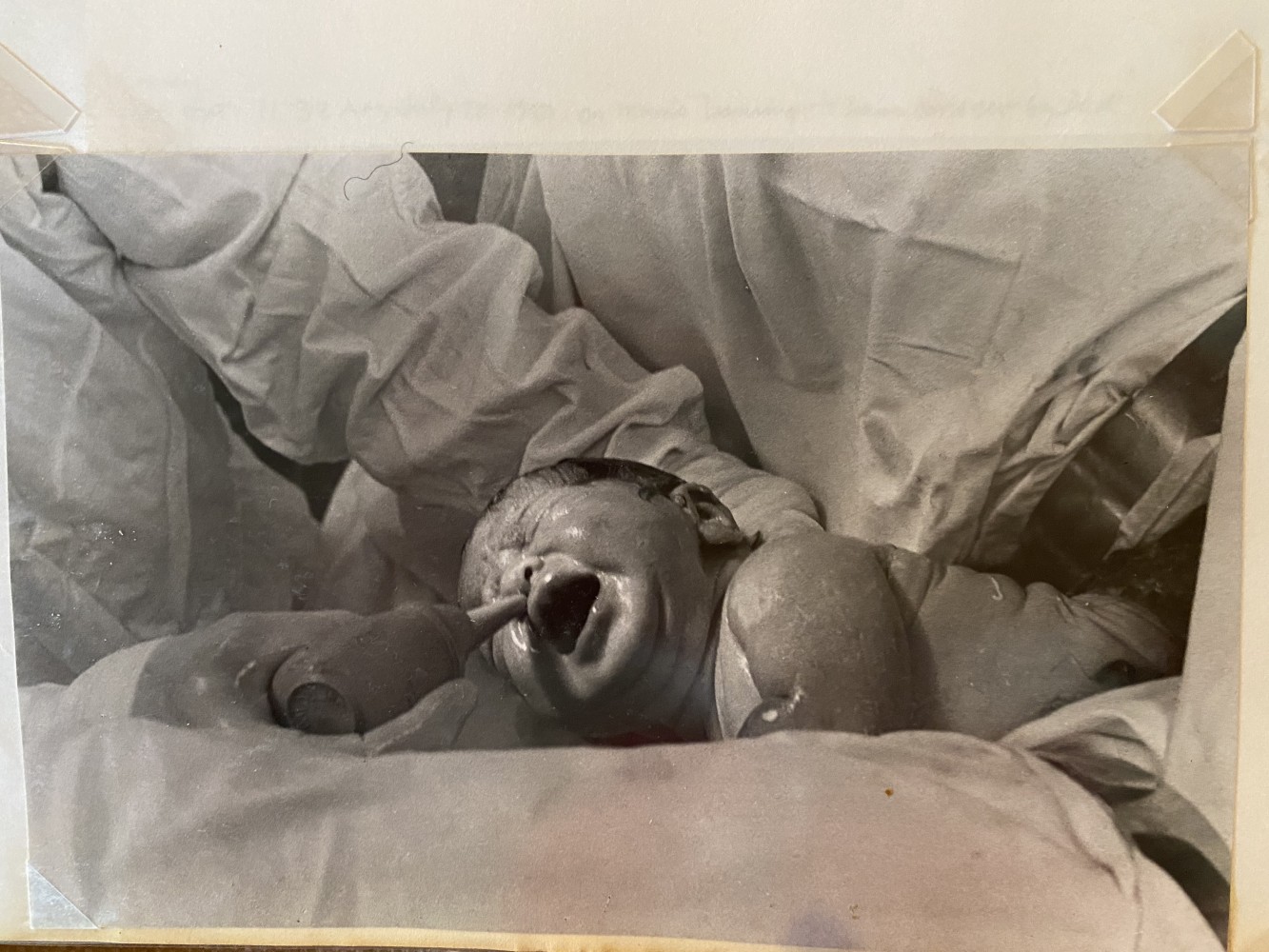

EMILY’S BIRTH, MY DAD [1980]

AGE ZERO – EIGHT

This is how it begins, I guess. The first pictures in my “baby book.” Looking at them now, I am focused entirely on the sheet covering my mother’s body. She is completely hidden, her experience left just outside the frame. A story untold.

I was a baby born out of a pile of sheets. But of course, she is there. I am tied to her.

My father is also missing from these photos. But of course, he is there too. He’s holding the camera. For the rest of my childhood, my mother will be the one taking the pictures. In every picture of me, she will be there too, hidden, invisible, on the other side of the lens.

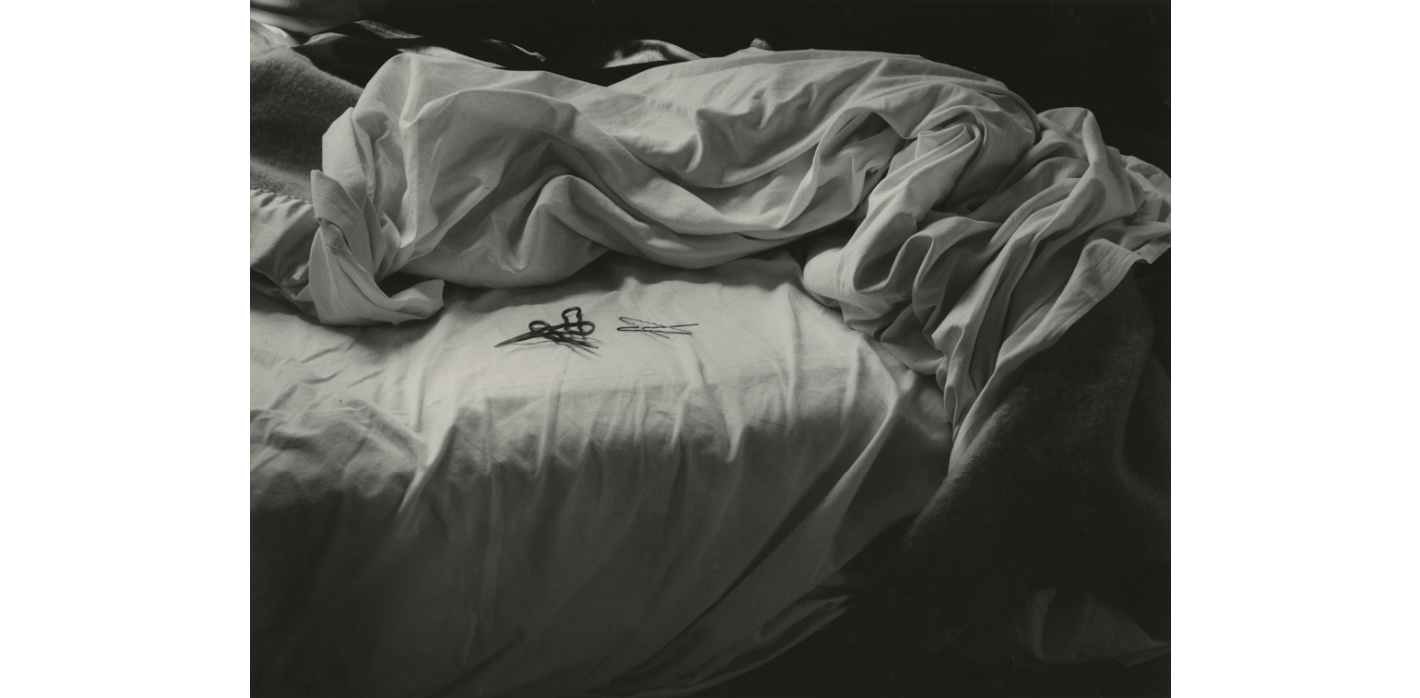

THE UNMADE BED, IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM [1957]

AGE NINE

I remember no photography prior to this photograph. The Origin of the World.

I found The Unmade Bed in a book about Bay Area photographers that my mother kept on a low shelf in the living room, next to the heating vent. The mornings in Northern California are cold, and before school I would sit on the heater and look at pictures until it was time to go. This was the first piece of art I ever loved.

I used to look at this photograph for hours wondering, is this a moment “before” or “after”? Are the hair pins discarded? Or waiting to be used? A woman alone? Or a woman missing?

The Origin of the World.

BRIAN, PHILIP LORCA DICORCIA [1988]

AGE FIFTEEN

Almost everything I loved at fifteen was melodramatic kitsch. [Highlight. Underline. Write in the margin “so true!”]

At fifteen, home was heavy. I was changing in a space that was holding still. I scrawled E.E. Cummings quotes on the inside of my closet door [LOL] and had big feelings about banal subjects like pasta [refused to eat] and the colour blue [had to wear].

I visited New York for the first time when I was fifteen. I bought this postcard [Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s Brian] at the MoMA gift shop. When I got home I tacked it to the cork board above my bed.

Philip Lorca diCorcia has big feelings about banal subjects. His homes are heavy, lit to capture the din of electric light and retro appliance. Daylight is never streaming through the windows. The outside is never getting in.

Two years later I put Brian and a handful of family photos in a cigar box and left for college.

You know when you go home for Thanksgiving? And you meet up with your friends from high school? And you no longer have things in common, but there’s something comfortable and baggy about it nevertheless?

That’s how I feel about Brian. If we met today, I’m not sure we’d be friends.

LOS ANGELES / EARLY EVENING, LARRY SULTAN [1986]

AGE TWENTY

The summer before my junior year of college I saved up to buy a copy of Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home. At the time it was the most expensive thing I had ever bought.

Something about the way Sultan rendered California as both home and theater felt important and familiar.

When I was in college, classroom conversations were dominated by Gregory Crewdson who was, at the time, turning western Massachusetts into Hollywood. In Sultan’s work I found an artist tackling similar concepts but a decade earlier and with a bit more nuance.

The photographer’s voice was honest and wry. This was work that was as much about the struggles and failures of the photographic process, as it was a commentary on suburban life. It was slippery and personal and funny and I loved it.

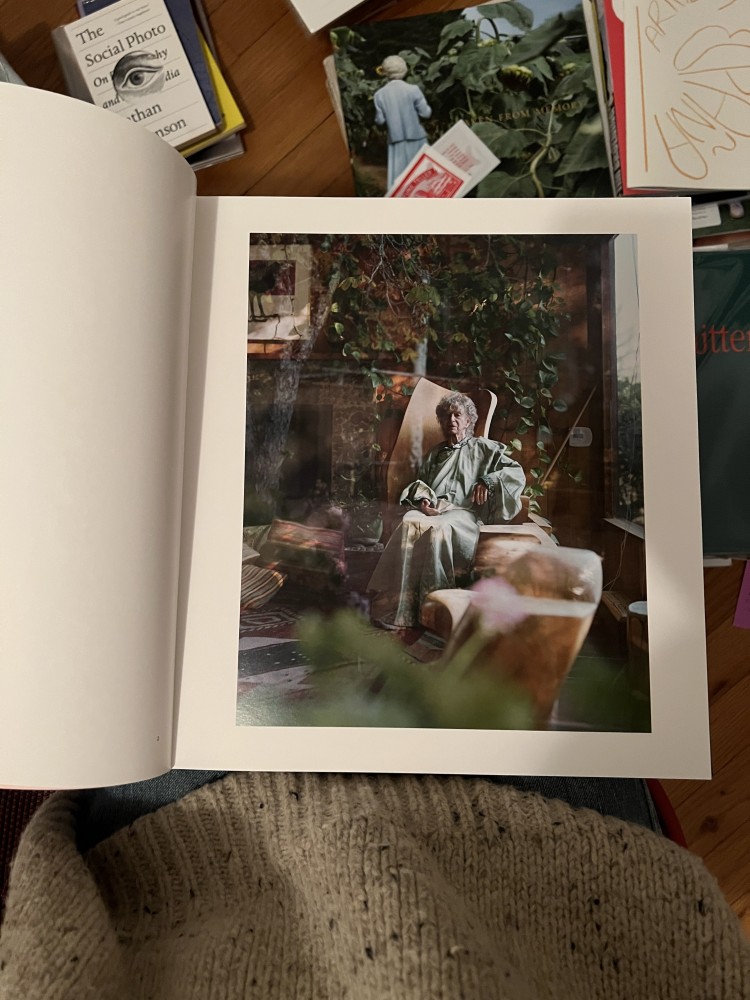

THE FIRST PAGE FROM I KNOW HOW FURIOUSLY YOUR HEART IS BEATING, ALEC SOTH [2019]

AGE FORTY-ONE

I am not a morning person. Occasionally, however, I wake up at 4am and am unable to fall back asleep. When this happens, I get up and tiptoe around my house like a god damn criminal until the rest of my family wakes up.

At 4am, California is drafty. The end of my nose is always a cold at 4am.

At 4am I drink tea so I don’t run the coffee grinder. My senses are heightened, I am in a foreign land. I sit at the kitchen counter on the stool my daughter usually occupies at breakfast. I pick up books of poetry, the ones I keep meaning to read; the air is too crisp to be sullied by scrolling. Wordle can wait.

On one such 4am this past spring, I made my tea and went into my studio. The night before I had received Alec Soth’s “I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating” in the mail. I had purchased it for the interview in the back of the book [it’s great! You should read it!!].

I have always appreciated Soth’s work. But it hadn’t “gotten in” – it hadn’t pierced me until I opened “I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating” at 4am.

I’m not sure I can explain how this book differs from the rest of Soth’s work, except that the photographer’s eye feels more present here, and also softer. Unlike earlier work, horizon lines are not always straight, the world is not always in focus. There is breath and accident.

The structures of home, windowpanes, door frames, curtains, mirrors, are central characters in this work, all layered on top of Soth’s classic gaze. It’s as if the photographer is saying “I am here!” “I am right here on the other side of this glass.” “I am not invisible.” “Can you see me?” “I am here with you, together but separate.” “I’m home.” Or maybe, “we are home, together.”

The first picture in the book is of the dancer and choreographer, Anna Halprin. She is at home in Marin County a few miles from where I grew up. A few miles from where I live now. My grandmother, Josephine, was Anna’s artistic director. She used to joke that her greatest contribution as costume designer in 1965, was to suggest the dancers go nude. No-costume as costume.

When I think about Anna, I think about dancing naked… I think about the texture of skin and coastal oak trees. I think about driftwood and crumpled paper, and the way the fog in Northern California shrouds the living. I think of my grandmother. I think of love.

I cannot tell you what it felt like to find Anna in my studio at 4am. But I think there’s a reason Giacometti built his palace at 4am: a sculpture of air and desire and memory. A “fragile palace of matches.” And I think there’s a reason why great photography can feel like home. After all, home and the camera have a lot in common, all frames and glass.

THE PALACE AT 4AM, ALBERTO GIACOMETTI [1932]

TODAY

OK. OK. Brass tacks. What I am saying is, when it comes to photography, my feelings are as follows:

Everything is tender. Everything is hilarious. So — OK! The last set of desert island photos:

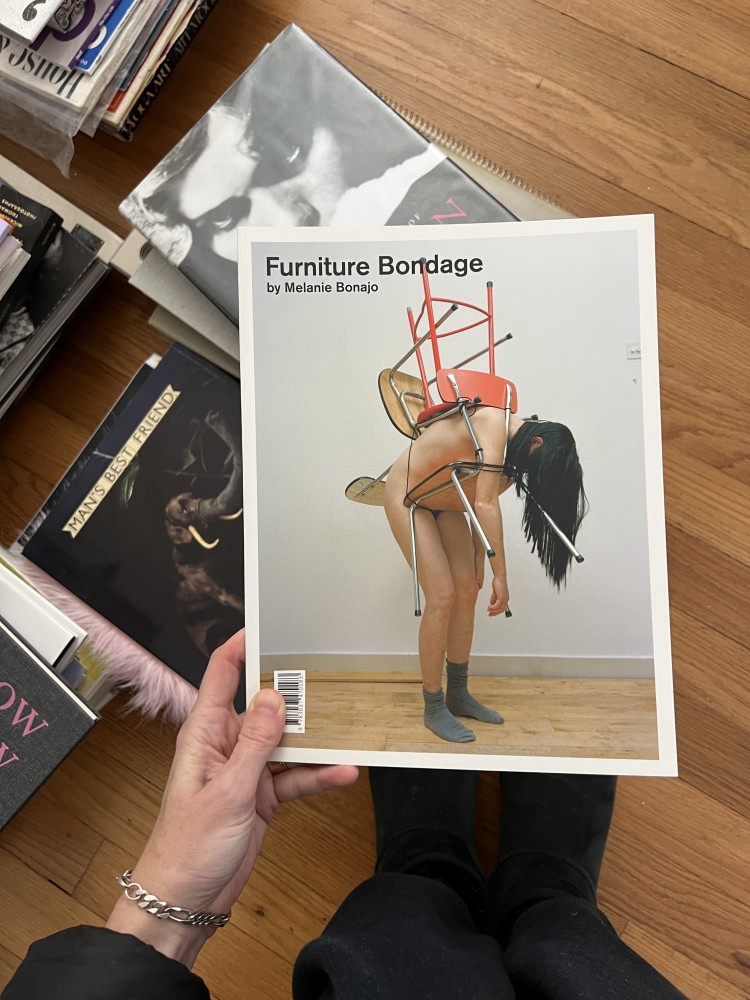

FURNITURE BONDAGE, MELANIE BONAJO [2009]

The softness of the body. The scaffolding of Home. The lightness of Photography.

FALSE EYES, WILLIAM WEGMAN [2019]

William Wegman is the Claud Monet of photographers. He’s a genius who might also be on a coffee mug.

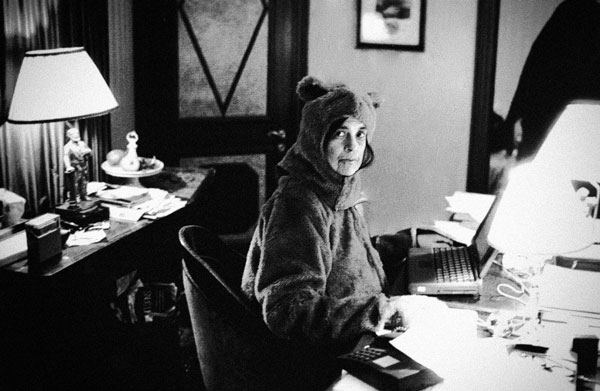

SUSAN SONTAG, ANNIE LEIBOWITZ [date unknown]

‘To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” — A woman in a bear costume.

A perfect photo.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?