Read Time 5 minutes

A portrait of Darrel Ellis: the artist & his demons

As I get acquainted with Darrel Ellis, I’m listening to Symphony by Zara Larsson — the sort of track I love to play on a trip to the gallery, because it reminds me what art does for my soul. Darrel Ellis was a legend of the 80s and arguably one of the great artists of the twentieth century. A painter, photographer, mixed-media artist and activist.

What’s so captivating about Darrel is his eccentric approach to the work. When I look at it closely, I witness sensuality: nostalgia and empathy rolled into one — captivating me, as great art does. Perhaps it’s all that Darrel and I have in common that grants me permission to understand him. By which I mean we had the same childhood, filled with subtle loneliness; us both realising our potential in the most vicious of spaces.

Darrel grew up in South Bronx, New York without a father. His father, Thomas Ellis, was brutally murdered by plain-clothes police officers just months before Darrel was born. As the middle child, Darrel grew up with the perfunction of not connecting with anyone in his family. That vile disconnection fastidiously developed him as an artist.

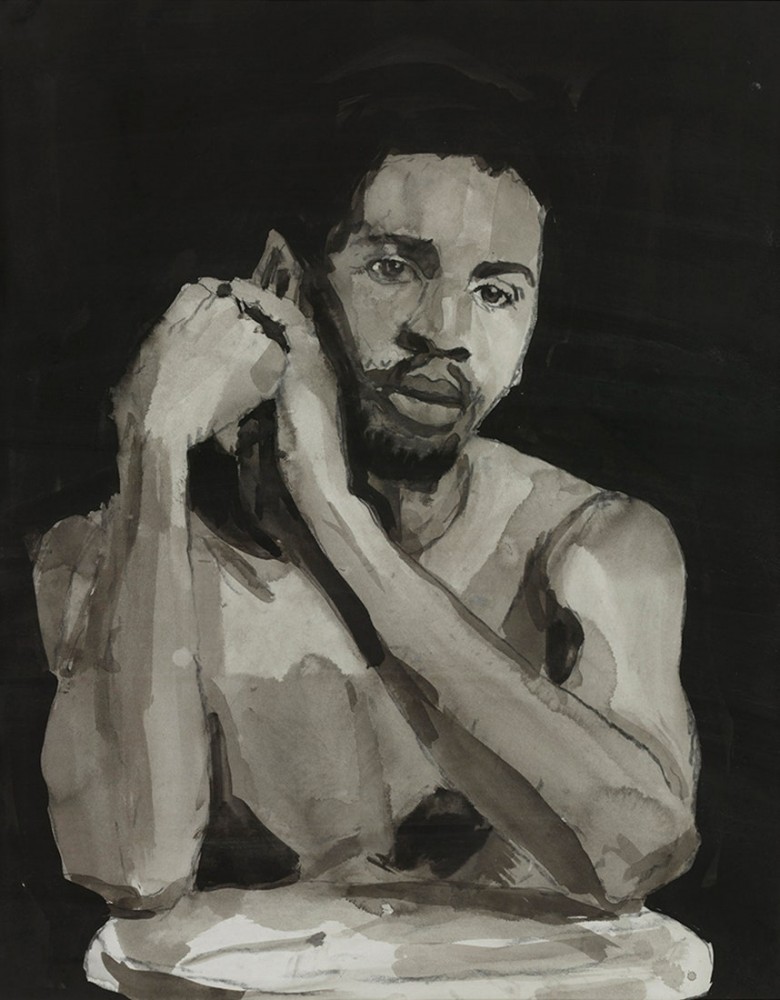

Darrel Ellis Estate, Courtesy Candice Madey, New York & Visual AIDS.

Darrel drew the things he wanted: cars and objects he dreamt of owning. His grandmother once mused that he was infected by white culture, because he had several white friends. She felt a need to warn him about the sort of society he was born into: a racist one, and that did something to Darrel. It caused an early fracture; instilled a fragility in him.

By the age of seventeen Darrel had developed a keen interest in visual art, thanks to the photography of his father. Not only did this allow him to become acquainted with the man he’d never met, it also inspired his artistic journey. During his formative years as a student he would frequently visit the museum, inspired by the grit of great artists like Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe, who would later serve as his role models.

Darrel’s works are a reflection of his father’s photography, which captures familial scenes in the South Bronx during the 30s, 40s and 50s. Darrel decided to use his fathers’ works as a basis for his art because it helped him maintain a certain distance and detachment from the reality he knew. In this way he would get to know the subjects, his family: Darrel’s grandparents, mother and sister, Laure.

His grandmother once mused that he was infected by white culture… She felt a need to warn him about the sort of society he was born into: a racist one, and that did something to Darrel. It caused an early fracture; instilled a fragility in him.

I’m most intrigued by Darrel’s mixed-media talent; his ability to fully transform a piece in existence, incorporate it into his painting and create something so sublime yet superficial. His self-portraiture shows a picture of a black and gay personality, existing in a society that is so widely intolerant — that transparency gave him the energy to resist against the limitations imposed on him as a black artist.

In several interviews, Ellis broached what it’s like being a black artist with a history of European exclusion to his art “people tell me sometimes that my work doesn’t look like it was done by a black person,” he said. He fervently resisted this reductive mindset [which possibly recalled the earlier warnings of his grandmother].

People tell me sometimes that my work doesn’t look like it was done by a black person

When I stare at Self Portrait After Photography by Robert Mapplethorpe, I see a man; hands clutched together, eyes searching for things beyond the charcoal-acrylic canvas. The image might have been made three decades ago but it houses that subtle enthusiasm for today’s art. That which Darrel taught his students in 1982 when he instructed at the Whitney’s ArtReach Program in New York.

If there is one thing I have come to realise from my analysis of art and its creators, it’s how drawn I am to art that bends the rules. And Darrel’s work is a prime example of this.

I imagine what it would be like for Darrel walking into Candice Madey gallery in New York City one day in May 2021, where the solo exhibition A Composite Being highlights his early and middle-career artworks. There would be this scintillating smile on his lips, the sort he wore when his work was featured in New Photography 8 at the Museum of Modern Art [MOMA], where he witnessed strangers appreciating his unconventional photography.

Darrel Ellis Estate, Courtesy Candice Madey, New York & Visual AIDS.

Before his death in 1992, Ellis drew a self-portrait which exuded despair. In the portrait, he wears a hat and sweater, his head bent to the right, palms out-stretched as if pleading for life. This portrait was different from the other self-portraits. Darrel wanted to portray his body and the ways it was failing him; his shrinking frame illustrating how HIV/AIDS was consuming him wholly. A portrait that shows not only the cruelty of the virus, but just how difficult it is to be Darrel Ellis: Black and Queer in an unaccepting city. A young man struggling with his demons to create art and survive a disease that [at that time] killed you without warning.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?