Read Time 7 minutes

Is the art world ready for virtual reality?

AND IS VR READY FOR THE ART WORLD?

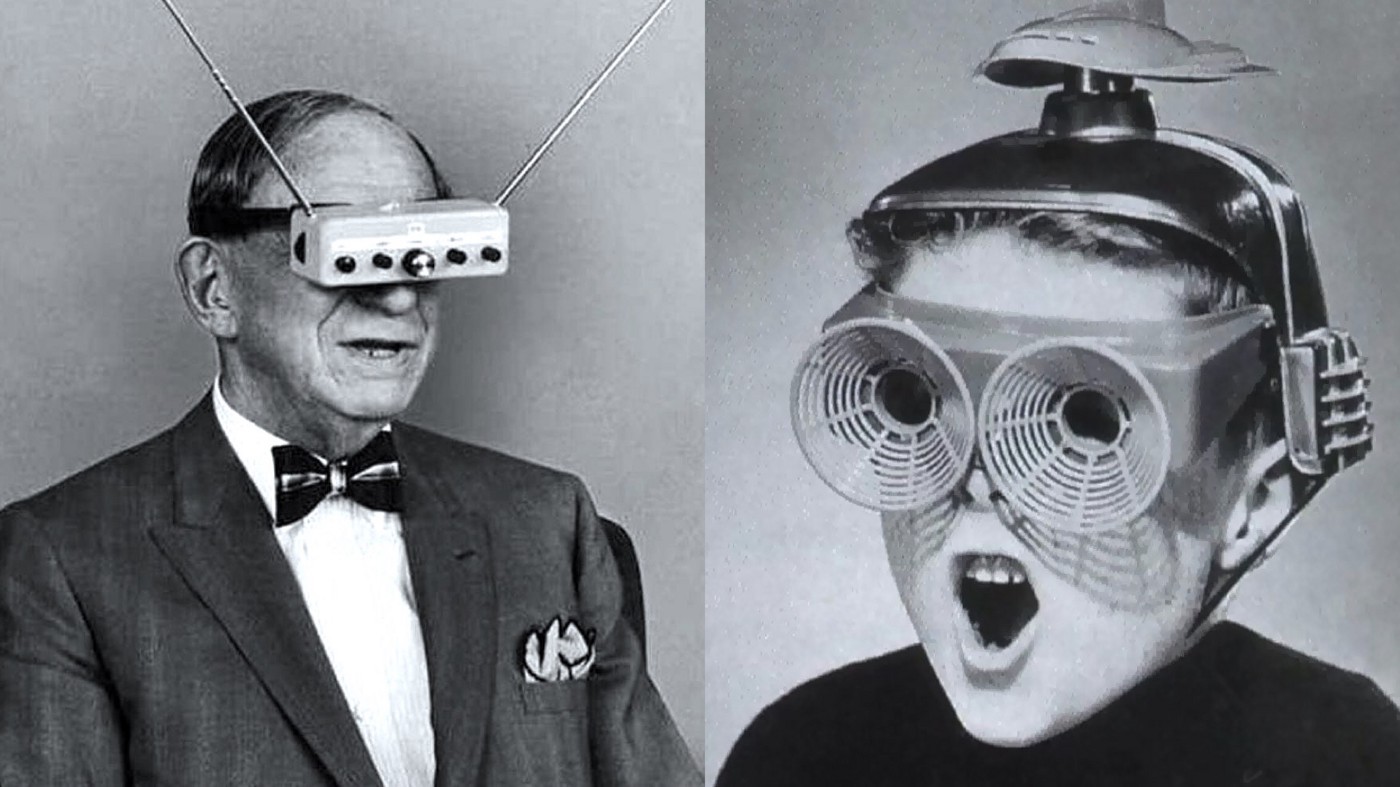

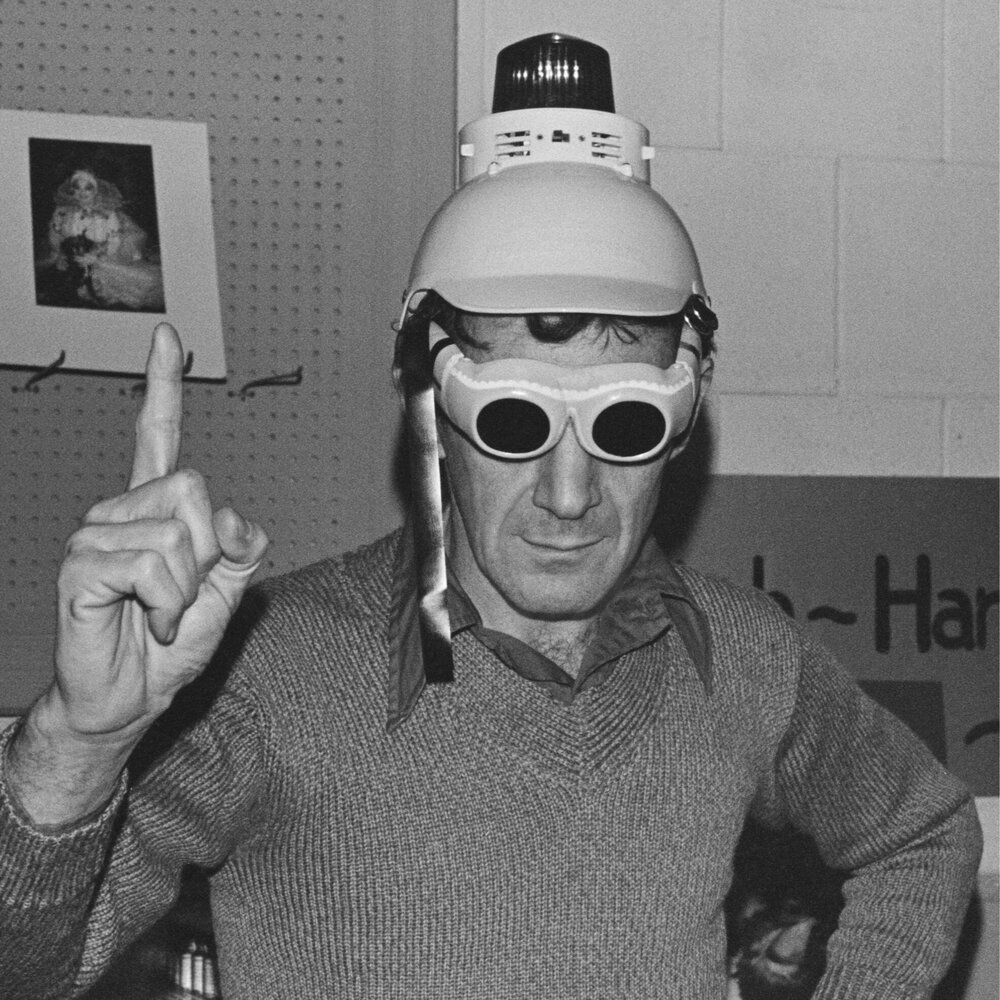

Virtual Reality headsets have existed since the early 1960s, but it’s only been in the last decade that they’ve found popularity in our homes, and even more recently that they’ve found a place in galleries and museums. But, while this technology isn’t as new as it may seem, it is still fighting to find its identity and function in the art sphere. VR headsets teeter along the line between the next big thing and clunky and passe, but have still made their way into the V&A, The Smithsonian, Tate, and the Louvre. It is a technology with huge potential, but have we run before we could walk by trying to harness it too soon?

VR pieces seem to come in two types, roughly categorised as ‘videos’ or ‘games’. Video pieces are 360 degree films in which the user can turn their head to see the video from new angles, but their path through the experience is pre-written and they can’t veer off course. Games are 360 degree environments through which the user can independently walk [or run, or fly]. Each has their own benefits, and both can suffer when their audience’s desires aren’t taken into account. 2022’s The Temple, a VR display of the work of Swedish master Hilma af Klint, had little going on below or behind the viewer during the video, and there was no way to fast forward. Trapping viewers in a 20 minute video does a disservice to the technology’s potential. On the other hand, the VR headsets at the Van Gogh Experience –– which opened near Spitalfields Market in July 2021 to mixed reviews –– were used by visitors sitting down and facing in the direction of the video’s travel which guided them through the wheat fields and French towns of the Dutch master’s adulthood. This consistent direction at least meant that viewers could truly look around and feel like they were exploring rather than simply being shown something. Equally, expansive ‘games’ environments may be off-putting to new audiences who don’t feel comfortable enough with the technology to command it.

It has been interesting to see what aims galleries have had in their use of this technology –– what goals are we setting for VR? The Temple display spent a long time showing af Klint’s work in a rudimentary mock up of a spiralling gallery not unlike the Guggenheim in New York, where an exhibition of her work was put on in 2019. If VR can be used to transport us beyond reality and to inhabit our wildest creative dreams, are we really just going to use it to recreate the inside of a minimalist physical gallery? Reproductions of physical spaces or exhibitions certainly have their benefits, and serve to bring art and culture to wider audiences. Visitors to Notre Dame this year can use a VR headset to see the cathedral as it was before the fire in 2019, and visitors to Southampton’s Gods House Tower can use a VR headset to view the wheelchair-inaccessible areas of the medieval tower. VR is a dynamic medium, but when designers are aiming for fantasy, they must push themselves to the limit to avoid disappointing results.

The artists currently having their work translated into VR experiences by wealthy institutions are also unsurprising Big Names who guarantee interest –– KAWS, Ai Wei Wei, Anish Kapoor –– but investment in VR work by emerging artists could give new talent worldwide exposure. The technology has tremendous potential to increase engagement way beyond those with existing social, academic or financial interest in the art world. New gallery Frameless in central London has leant into the public desire to engage with art in a way other than to look at framed canvases, by creating immersive environments which play on the same goals as VR experiences. Unlike whole-room installations, like Frameless, VR headset artworks will be difficult for museums and galleries to monetise [especially when showcasing work by new artists], and so will likely slip down the list of priorities. Another show of large-scale paintings, anyone?

If VR can be used to transport us beyond reality and to inhabit our wildest creative dreams, are we really just going to use it to recreate the inside of a minimalist physical gallery?

There are several practical elements which make the headsets tricky to incorporate successfully into cultural spaces. In order to engage with a VR headset experience in a meaningful way, viewers need to be in a perfectly controlled physical environment. VR headsets are all about giving yourself up to a new reality, and it’s hard to keep that fantasy alive when you’re standing in a loud space, overhearing other people’s conversations and trying to keep an eye out for whether your bag by your feet is getting nicked. Even the most spectacularly executed VR environments would fail to reach their impact potential when experienced in a disruptive physical space. If VR performs best when used in isolated environments, are these something that galleries and museums are happy to dedicate space for?

There are other physical issues which will need to be hammered out before VR can truly flourish as an educational and artistic tool. Institutions will need to have a system in place for cleaning the headsets between uses, and have staff on hand to explain the technology to visitors. Galleries will want to avoid the cost of upkeep of these machines, or the price of buying enough of them to reduce queue-times.

When it comes to accessibility, there is no one answer. For some neuro-divergent and disabled viewers, the heavy, tightly-strapped headsets may be off-putting, and without control over the brightness, audio volume, and audio captioning, this technology can prove a deeply unpleasant experience. For others –– and especially if we find isolated spaces in cultural institutions to allow users to wear these headsets in silence –– VR can offer access to exhibitions and experiences which might be otherwise inaccessible. A quiet space where people can move away from overstimulation in the museum/gallery space is surely advisable, whether or not visitors decide to use a VR headset while they’re in there. Creating more experiences where the work comes to the viewer, rather than the viewer needing to physically navigate the work, will offer new experiences to viewers for whom viewing static exhibitions poses a physical challenge.

The images used for VR experiences –– which are regularly brought in by the designer from a catalogue of other artists’ creations –– do often have a stock image feel to them, meaning these worlds feel like first drafts rather than final products. It feels like getting to the first stage of perfecting teleportation –– allowing you to teleport from your bedroom to your hallway but no further –– and then sending out 10,000 units to every Argos in the country. In the case of af Klint, the goal behind The Temple project can’t really be faulted: an immersive world of art which surpasses physical boundaries would be what af Klint would have wanted for her spiritually-led practice. We should have waited another decade to give this to her, when the technology has met its potential.

Once it is perfected and affordable [which will sadly be a while after it has been rolled out to its initial wealthy audiences] VR technology will truly come into its own. The technology could allow people to view show stopping exhibitions and physical art experiences in capital cities from the most remote corners of the planet. VR also offers new options for practising artists to create new works, rather than just a showy way for gallerists to curate retrospectives. The room it offers artists to play and experiment is vast –– and may one day be practically limitless.

We can’t un-invent VR. But perhaps we could all agree to close our eyes for a few more years and revisit the technology once it has caught up with its promise.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?