Read Time 11 minutes

Photography & poetry: A female perspective

Rebecca Batley examines some of the ways that photography and poetry speak to the female experience when the two art forms intersect.

The very first image ever to be taken by a woman was Constance Talbot’s blurred photograph of a verse written by the Irish poet Thomas Moore, and from that moment the two art forms of photography and poetry have been intertwined – not only with each other, but also with womanhood, speaking to the contemporary feminist struggle of their subjects and of society.

Present day photographers such as Anna Orlowski and the late Maud Sutler have made explicit poetic references in their work in order to comment on the female condition, and there is a powerful canon of poetic and literary figures including Virginia Woolf and Margaret Atwood, who reverse the process, constructing their written work with explicit or implicit illusions to visual art.

These two art forms have twisted, turned, and evolved together, held hands or butted heads.

Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, was not only a bewitching story-teller who built worlds through his powerful command of language––in prose and in nonsense verse––but a keen photographer too.

His early images of Alice Liddell, his muse, taken shortly after he got his first camera, are an interpretation of the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Dodgson loved poetry but he also felt, as he would later write in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland [1865]: ‘What is the use of a book without pictures?’ For him, words and images were always in dialogue.

Photography was in its infancy when Dodgson began to dabble, and he was an early pioneer of the wet collodion process. Photography, he felt, gave him the ability to both test his skill and apply the pictures he wanted to the poetry he enjoyed. Dodgson’s most famous image of Alice, The Beggar Maid [1858], is a response to the Tennyson poem of the same name, in which King Cophetua falls in love with the titular beggar maid. In the poem the maid is praised for her ankles, beautiful eyes and dark hair, all of which are reflected in Dodgson’s image. Alice’s gaze, at once defiant and worldly, entrances and troubles me, as it has done many others ever since its creation. Some argue that Dodgson’s image is a literal reflection of Tennyson’s work, designed to illustrate and accompany the text, and that it should be regarded as one of the first examples of narrative artist photography; embodying Tennyson’s words. The two men’s association was a long one, when Dodgson heard that Tennyson too was interested in photography he arranged to take a photograph of Tennyson’s sister-in-law Agnes Weld, to whom Tennyson addressed a sonnet. From there, his attention turned to the Liddell girls and to Alice in particular. The ten year old Alice, so beautifully captured, was the inspiration for his own poetry, most notably in his poetic preface to Alice, making the relationship between poetry and photography somewhat reciprocal.

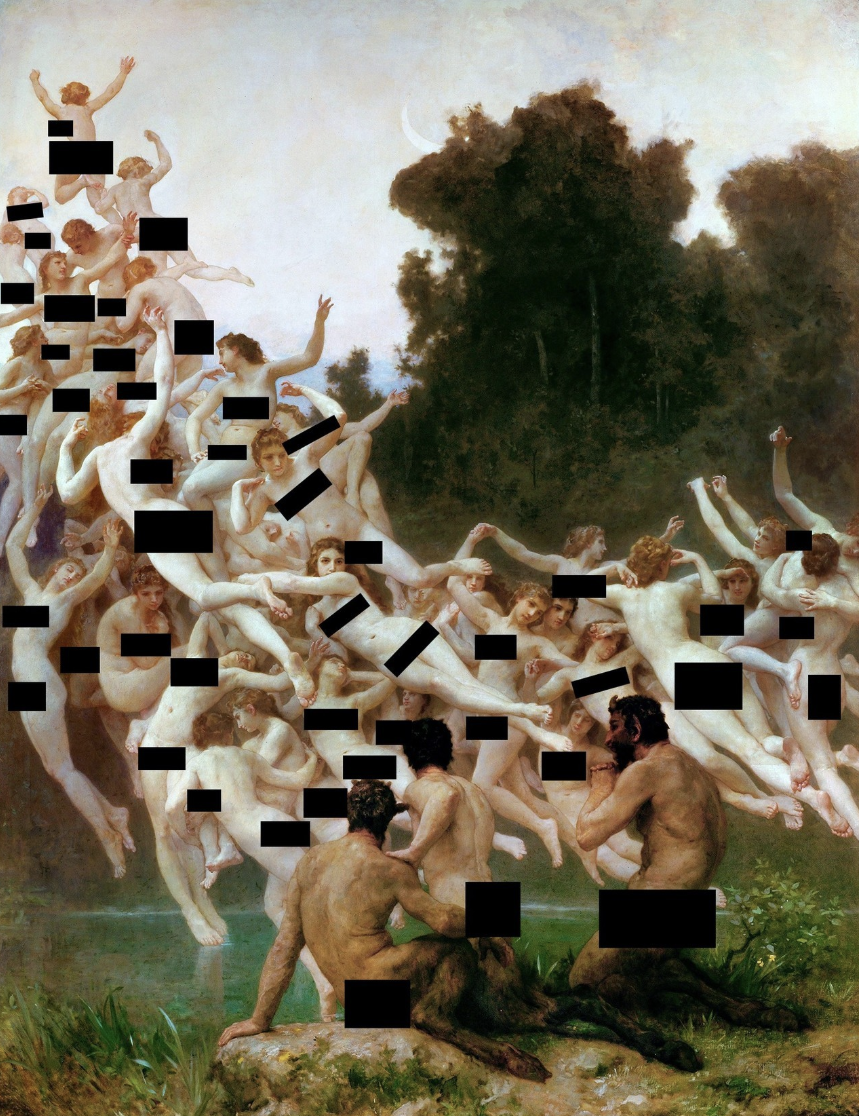

The fact that Dodgson used girls such as Alice, the daughter of a dean of Christ Church college Oxford, rather than actual beggars [numerous of whom could have been found on the streets of the East End or Haymarket], adds weight to the idea that these images were intended to be artistic reflection and not documentary realism – photography in the high-art tradition akin to Oscar Gustave Reijlander, a pioneering Victorian photographer who collaborated with Charles Darwin, or to Julia Margaret Cameron, who also found much creative inspiration in the work and companionship of Tennyson. As such, the photography of this period in England is often viewed as the launch pad of the fruitful relationship for itself and poetry.

There is a darker interpretation of these images though, one which speaks to the subjugation of women and girls. Author Francine Prose characterises the expression on Alice’s face in these photographs as one ‘we associate with intimacy, the unwavering focus an adult woman might turn on her husband or lover.’ The problematic sexual implications of the composition are intensified by the contemporary associations of the beggar maid with connotations of child prostitution. The uncomfortable connection between his photography and inappropriate eroticism was one that Dodgson and others were cognisant of in their day, and has led now to Alice being regarded, by some, as the face of Victorian exploitation of young girls, a catalyst for the fledgling feminist movement. Scholar Steven Marcus argues that Dodgson’s photography should be regarded as nothing short of exploitative erotica and that its association with poetry is merely used to give the images a thin veneer of respectability. In support of this argument is the fact that Dodgson in his diaries expresses self loathing, but never explicitly states why. The fact that Dodgson and Alice’s relationship came to a crashing halt, with some evidence implying that he had crossed the line of platonic affection, lends credence to Marcus’s argument. Even within the context of Tennyson’s poem, the photographs speak to an uneasy reality for contemporary womanhood.

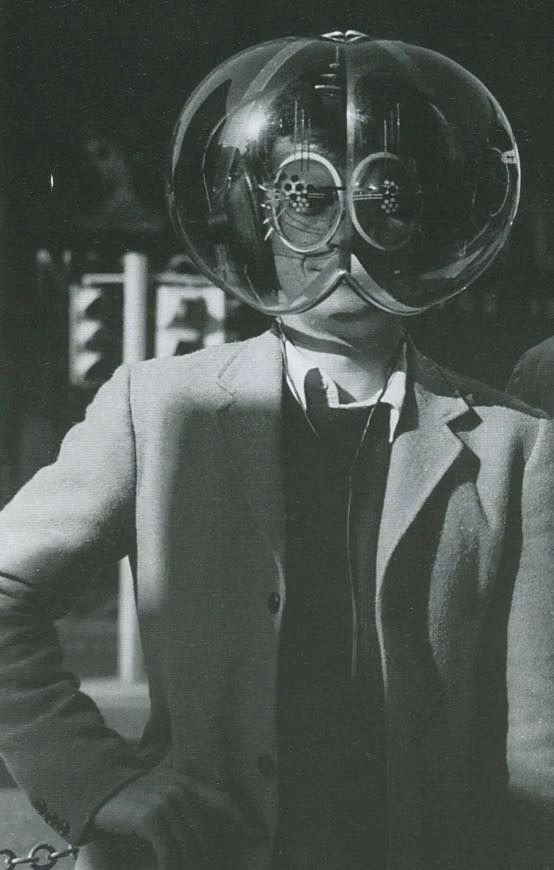

The pairing of poetry and photography had already existed for nearly a hundred years [see publications such as Adelaide Leeson’s Pictorialist photographs in the 1908 edition of FitzGerald’s Rubàiyàt of Omar Khayyàm] when in1936 it was given a name: photo poetry or a photo poem, as coined by one Constance Phillips. The connection was immediately subjected to analysis, with Nicole Boulestreau writing lyrically that: ‘In a photo poem meaning progressed in accordance with the reciprocity of writing and figures; reading becomes interwoven through alternating restitchings of the signifier into text and image.’ Constance Phillips’s work is bold and intriguing, her images being simultaneously representative of works she in evoking and entirely independent of them. Her stark image of a man’s silhouette in front of the contemporary New York skyline was created to accompany the poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel by Sir Walter Scott, with its famous lines breathes there a man with soul so dead, / who never himself hath said, / this is mine own, my native land. But it could, for example, just as easily apply to the plight of those men and women like herself, who were seeking to forge a new path as an independent working woman, and in many ways unnatural land in which to live. It speaks to the specific contents of a specific poem, but also to a universal experience that could be recognised and understood even by those unfamiliar with Scott’s verses. Phillips was a pioneer in this new land, seeking to gain both recognition and equality in the male dominated landscape to 1930’s photography. Her work demonstrates the evolution of the link between poetry and photography and embodies the changing role of women: a time when women were no longer simply subjects, but were becoming authors of their own image and narratives.

It was taken some time ago.

At first it seems to be

a smeared

print: blurred lines and grey flecks

blended with the paper;

then, as you scan

it, you see in the left-hand corner

a thing that is like a branch: part of a tree

(balsam or spruce) emerging

and, to the right, halfway up

what ought to be a gentle

slope, a small frame house.

In the background there is a lake,

and beyond that, some low hills.

(The photograph was taken

the day after I drowned.

I am in the lake, in the center

of the picture, just under the surface.

It is difficult to say where

precisely, or to say

how large or small I am:

the effect of water

on light is a distortion

but if you look long enough,

eventually

you will be able to see me.)

This is a Photograph of Me, Margaret Atwood

Both of these cases see photography embodying and responding to words, but by the late twentieth century the focus has flipped and poetry is just as likely to be taking the initiative in the relationship. This can be best seen in Margaret Atwood’s poem This is a Photograph of Me, which explores the links between the two art forms and has spawned numerous photographic responses. The poem talks about a quite literal photograph, one which was taken some time ago, and, at first it seems to be/ a smeared / print: blurred lines and grey flecks / blended with the paper. The eponymous photograph was taken of a woman who has drowned. Lurking just beneath the literal surface of the water, the poem explores the role of women, and the issues facing women in the lead up to the second world war: the water which stops her voice is in fact the white male majority. Whereas photographs are usually used to give a more detailed and ‘definite’ sense of the person, here the photographs in fact obscures the narrator’s realty. She is not a specific woman, rather, through her photographic image she embodies all women of that era whose ‘lines are blurred’ by the prevailing male dominated society. Photography is giving her the medium through which to reflect on society, and the feminist struggle in a broader sense. The evolution of this verbal and visual imagery in Atwood’s work, in the words of scholar Dr Madeleine Davies, ‘reveals the extent to which these two forms consistently work away from seamlessness to challenge the integrity of self representation.’

The term ‘ekphrasis’ chronicles a written or verbal description of a visual image which is, in and of itself, a work of art. Conversely, what is configured as a visual must be regarded as always lying within the parameters of linguistic structures when the two art forms interact. In response, photographers have tried to reflect this ambiguity, and interpret the words in a reversal of the process exemplified by Dodgson. Many centuries ago the Roman lyric poet Horace said that a picture was a poem without words: both being representations of ‘something,’ and each capable of being a metaphor for the other. Individually and together each can, and have, been used to challenge assumptions about language, image and meaning in order to illuminate the lives, and struggle of women for acceptance and equality.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?

![Ada Alti | The real cost of working in the arts [if you're not a nepo-baby] | Darklight Digital](https://darklight-digital.com/media/2023/08/prime-matter-exploreher-5x5.jpg)