Read Time 11 minutes

Vanessa Bell: A Pioneer of Modern Living

From a repressive nineteenth century childhood to setting the standard for a free-spirited, creative existence, Vanessa Bell was light years ahead of her time.

A new exhibition at London’s Courtauld Gallery calls her a ‘pioneer of modern art.’ For Darklight, contributor Rebecca Batley explores how photography can show us that she was also a pioneer of modern living.

What did the ideal Victorian women look like? Doe eyed, blank expression, posed stiffly and dressed in smart, confining clothes. One of the earliest surviving photographs of Vanessa Bell, née Stephen, as a young woman, depicts her just like this. In 1902––just one year after Queen Victoria’s death––Bell was 23 years old, and was photographed by George Charles Beresford in much the same manner as any other well bred young woman of the age. She stares out at us blankly and unsmiling. She is seated indoors on a plain background and her modest dress is adorned only by a simple necklace. Bell [1879-1961] is prim, proper and looks in every way like the ideal upper-middle class lady, not a hint of the subversive life that lay ahead of her. No personality at all in fact. This was, of course, the point, for at the time her father Sir Leslie Stephen was dying, and the portrait sitting had been arranged by half-brother George Duckworth, who was preparing to assume responsibility for his two half-sisters: Vanessa and her younger sister Virginia. The white dress stands in contrast with the anticipated period of mourning, and depicts them as pure, virginal young women. The photographs could be used to help entice suitors when they inevitably withdrew from social engagements for a time following their fathers death. In essence, this portrait was an advert, introducing the young Vanessa to the marriage market. Beautiful, still and silent. Devoid of the exuberance of childhood. In short – the ideal bride.

In these early photographs of Bell there is no allusion to the fact that, by this time, her life as an artist had already begun. Bell had been taught to draw by the watercolour artist Ebenezer Wake Cook before studying at the Royal Academy in 1901, under the tutelage of John Singer Sergeant. This was no honorary position either, her first commission as a painter had come in 1905 when she painted Lady Robert Cecil. An image taken of Bell painting this portrait could not be further removed from the idealised Beresford image: in it she is seen working, in a domestic room, hair pulled back simply and an apron over her dress. For a lady to permit herself to be recorded for posterity in this way was truly radical at the time, and it must have made an impression on Bell, as it was an approach she too adopted when she came to take photographs of her own.

Although painting was her true love, photography was a constant throughout Bell’s life. Indeed it was in her blood: her great aunt was the pioneering photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who had immortalised her mother and their family in numerous wet plate photographs. Bell received her first Box Brownie camera by the year 1897. She kept albums of photos from an early age; of herself, and those which she had taken. Many of these remain at Charleston, her home and great legacy, and have been crucial to scholarly understanding of Bell and the history of Bloomsbury.

Following the death of their father, Bell moved with her siblings from the family home in Hyde Park Corner, to Bloomsbury, where the eponymous group of artists and writers was formed, meeting weekly at their new house in Gordon Square. She married the critic Clive Bell in 1907, and although they would remain married all her life, the couple effectively separated in 1916 and had what we would term today an ‘open marriage’, defying the conventions of early twentieth century society and taking numerous lovers. For Bell this included, most notably, the homosexual artist Duncan Grant, with whom she had a daughter, Angelica, and lived with for the rest of her days in what her sister Virginia Woolf dubbed a ‘left-handed marriage’.

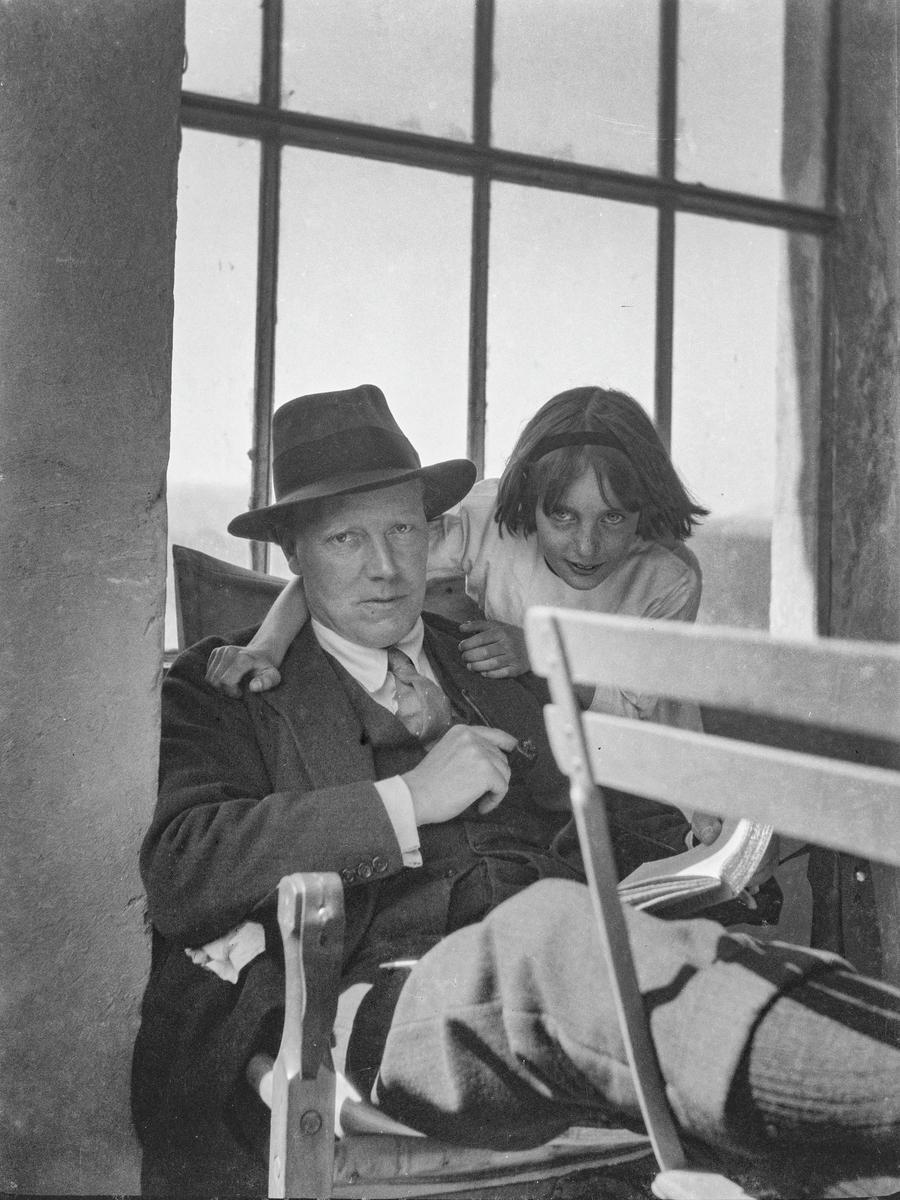

The few photographs that exist of early Bloomsbury are chaste and formal; the fashion is still typically modest, the poses not yet intimate. Things changed when the group began to disperse outside of the capital, taking various country residences (with Bloomsbury remaining as the nucleus of the cell). As a more rural existence took hold, the photographs too become looser, and more closely resemble the liberated lives that were being led. The pictures themselves are not radical in an artistic sense – Bell was a remarkable artist in her own right, but her photography skills were not especially remarkable. But, what the pictures show truly was radical. A web of people, connected by friendships, sex, art, and a shared rejection of the conventions of their upbringing, living life on their own terms. We can trace the development of these lives through Bell’s photo albums.

Bell arrived at Charleston with Duncan Grant, and his lover David Garnett, in 1916. For Bell, the house was love at first sight. Leonard Woolf observed, ‘the most delightful house … it has a charming garden, with a pond, fruit trees and vegetables, all now run rather wild, but you could make it lovely.’ Indeed they did, the house became an art piece, with a constant revolving door of visitors including Virginia and Leonard Woold, Roger Fry, E.M Forster, Lytton Strachey and Carrington, John Maynard Keynes, and many other influential figures of the day. As George Varley describes it for Inigo House, Charleston was Bell’s ‘counter cultural escape, a haven away from the morals of London life that allied them to do things their own way.’ Such a refuge was badly needed, not only for the many queer members of the group, but for Bell herself, who, during the interwar period, was living in what might now be described as a polycule, a concept that would have seemed foreign and even perverse to mainstream society. Even today, the idea of a polycule is alien to many, but the idea of it continues to fascinate in a world where monogamy is the norm. Bell was a pioneer in rejecting this ideal.

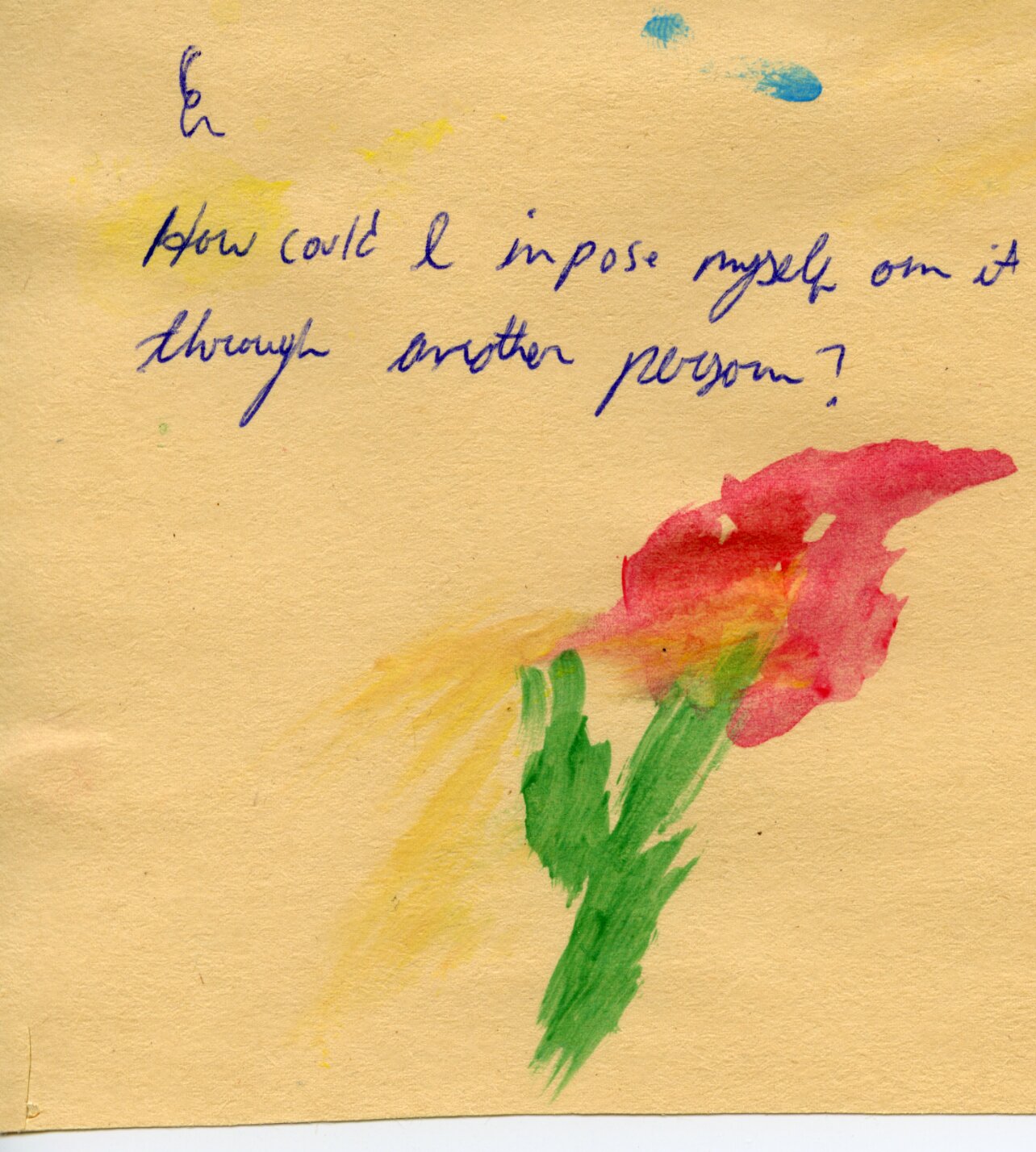

By the 1920s Bell was capturing dozens of images of domestic scenes, carefree moments, both indoors and outdoors at Charleston. Her son Julian called the images ‘representations of sentiment memorialising and celebrating female domestic life.’ They portray women, who Bloomsbury scholar Emma Carr observes: ‘dominate their space whilst performing domestic activities.’ This domesticity has led to accusations that Bell’s photographs did more to support traditional femininity than reject it, and that through her focus on femininity and the home her photography undermined the work of other contemporary female artists, who were striving to show that a woman’s place was in fact, not in the home. To accept this view, however, is to misunderstand what Bell’s domesticity symbolised. In a house maintained by numerous servants, her home was a canvas for her self expression, an extension of her artistic practise, and the backdrop for a community where the sexes lived together harmoniously and equally. Charleston was liberation.

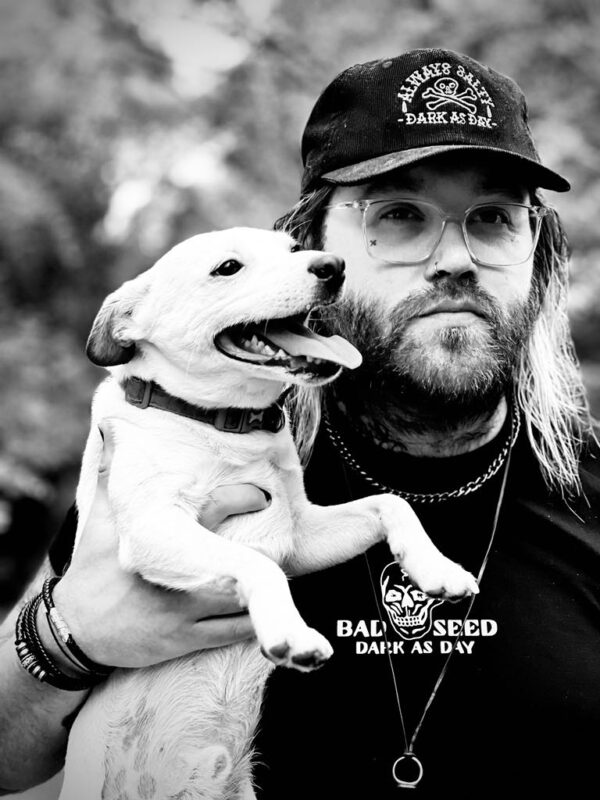

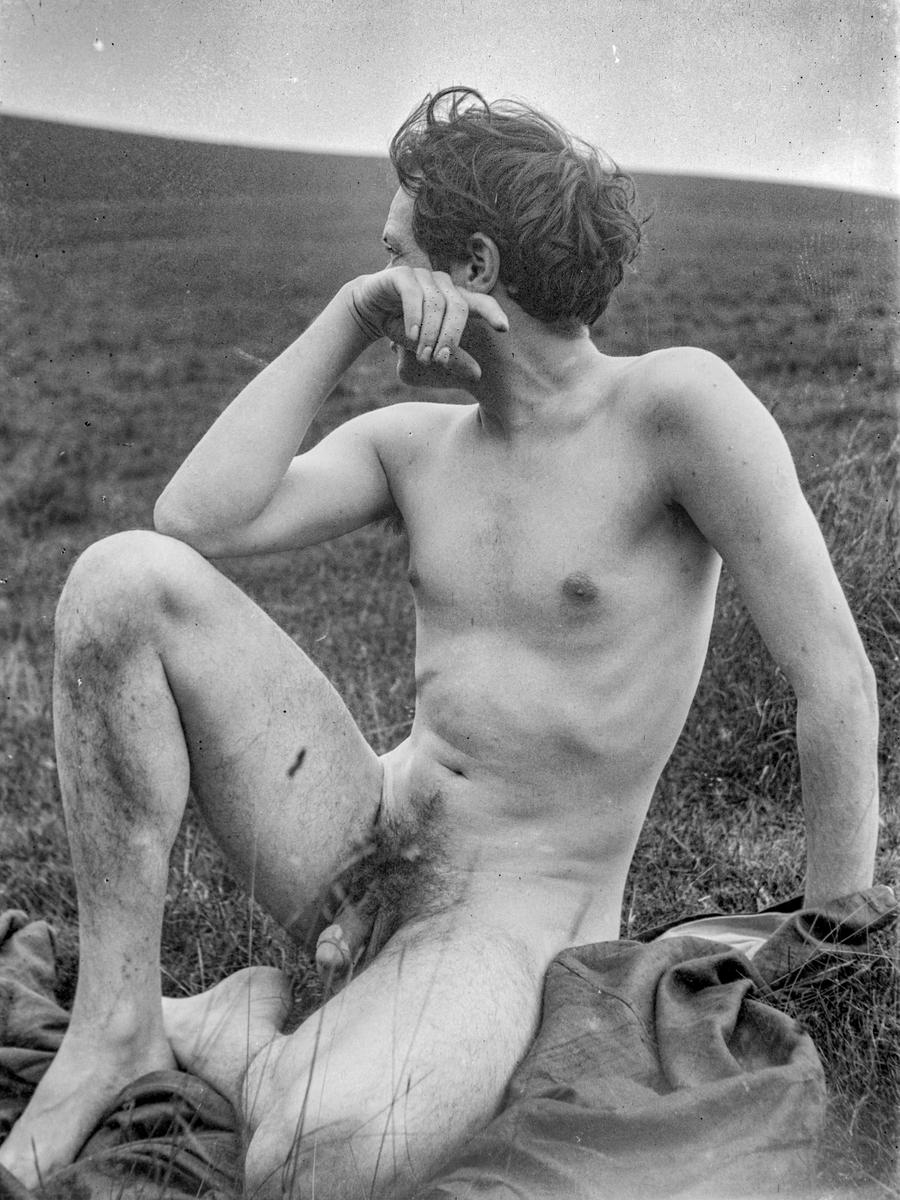

In these carefree images Bell laughs, as do her friends and family. We are treated to a glimpse of Grant laying sprawled on the grass, smiling back at Bell with intimacy and connection. In many outdoor photos he is bollock naked, a queer body at peace with his sexual self. This is a gay man, whose sexuality was illegal and whose existence threatened rigid rules of the society in which he lived. For him to be revealed in such images as his ‘true self’, shedding the stigma of his sexuality and revealing the body into which he had been born in all its glory, was, at the time, radical in the extreme – and of course a dramatic contrast to the kind of images taken of their parents’ generation, or their contemporaries who lived more conventionally.

Likewise, those early studio portraits of Bell could not be further from an undated photograph of the artist clasping hands with Molly McCarthy, totally naked, posing dynamically in her studio. In this image Bell is truly revealed to the viewer, there is nothing contrived or erased––neither woman does so much as suck in her stomach, let alone concealing their spectacular bushes of pubic hair––she is utterly at ease with herself, her body and the environment in which she lives. If the Victorian woman was detached from sexuality, here Bell has shed these restrictions, and presents herself with zero artifice.

Bell’s photographs of the Bloomsbury group, at which she and her home at Charleston were the very centre, reveal them as a bridge between the past and the future. The group’s members were Victorian children who grew up to pave the way for future generations, none more so than their own children, to live a very different kind of life, one free from the shackles of repressive morality and traditional manners. By the time that Vanessa Bell died in 1961, more and more people were able to choose the kind of life they had made, irrespective of class, economic background, sexuality and gender. The cultural and sexual revolution of the 60s was prefixed by Bloomsbury’s activities in free love, gender bending and progressive sexual dynamics, a blueprint for these later generations. The photographs show a kind of dreamy utopia of perpetual summer: an ideal world. Naturally it was not like that at all times, the group was beset by tragedy, but that’s not what the pictures say. Instead they are an inspiration for a different kind of life and perhaps a better and more tolerant way of living, made all the more inspiring by the challenges they had to overcome in order to get there.

END

Vanessa Bell: A Pioneer of Modern Art runs at Courtauld Gallery from 25 May – 6 October 2024.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?