Read Time 8 minutes

Historical Heroines: Nobody was doing it like Julia Margaret Cameron

How a middle-aged woman challenged photographic convention with her artistry, and the story of how our paths intersect in one Hampshire village.

I did a short course at the Courtauld Institute this year titled Photography and the French Avant-Garde from Delacroix to Cézanne. It was great, learning more about the ways the artistic mediums of painting and photography informed and interacted with each other in the latter’s early years. In one Q&A session I asked the lecturer a question along the lines of when exactly we began to see the artists’ hand at work in photography, rather than the camera just being employed as a documentary medium capturing the world in as literal a way as possible, with little regard for composition, form or tone. The lecturer told me that Julia Margaret Cameron was probably one of the earliest examples of a photographer who developed a set of artistic signatures with the click of her shutter, and, let me tell you, I was thrilled. And not just in a yaaaaaaas queen pussy power kind of way, cool as it is that a nineteenth century woman was such a pioneer in the course of art history.

The train station just across the road from my former sixth form college in the New Forest doesn’t have much to commend it, but one surprising and lovely wall of the ticket office should be worthy of tourist attraction status in itself, currently reserved for the national park it services: a set of photographs gifted to the station by the artist, Julia Margaret Cameron, over 150 years ago.

Okay, these aren’t the originals, they’re copies, which apparently were made in the 1930s when the originals were moved to the rail company’s London headquarters for safekeeping, and then lost. But I’m not sure I mind that much, if they had the originals I imagine they would have been donated to a museum or sold off––for hundred of thousands of pounds no less––long before I passed by them everyday on my way to my a-level classes [photography, philosophy, fine art, for anyone interested]. And what an auspicious backdrop with which to study photography!

Mrs Cameron, as she was known, may have been given her first camera by her daughter as a plaything with which to occupy her, but it is true that she had some pretty strong creative pedigree already. The Pattle sisters, of whom she was one of seven, were known in the late-Georgian period for their unconventional dress and manners––raised in colonial India they preferred to dress as the native people did––and in her married life she ran in highly cultured circles: Tennyson, Thackeray, Rossetti and more. Her sister Sara hosted a salon in her home in Kensington where a number of the Pre-Raphaelites convened, and another sister, Maria, was mother to Julia Stephen and grandmother to two people you may know a thing or two about: Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Her career was short but prolific, she received her brass Jamin camera lens when she was almost 50 years old, and she only spent another 12 years taking pictures, but the estimated number of those pictures is over 900, many of which are now lost [by South Western rail, for example].

‘… My first successes in my out of focus pictures were “a fluke” = That is to say that when focusing & coming to something which to my eye was very beautiful I stopped there, instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other Photographers insist upon.’

In 1874 Julia Margaret begun a memoir of sorts, describing the first decade of her newfound career. Named Annals of my Glass House, the surviving pages are in possession of the Victoria & Albert Museum and tell of how she came upon what would become her signature style: ‘… My first successes in my out of focus pictures were “a fluke” = That is to say that when focusing & coming to something which to my eye was very beautiful I stopped there, instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other Photographers insist upon.’ While her contemporaries were perfecting technique in order to capture the world in as much true-to-life sharpness as possible, Julia Margaret was experimenting with the technology and finding out what new aesthetic could be achieved. Nor was she concerned with imperfections in the printed images; scratches, blotches and blurs were left unretouched. The others were doing science, she was doing art, baby!

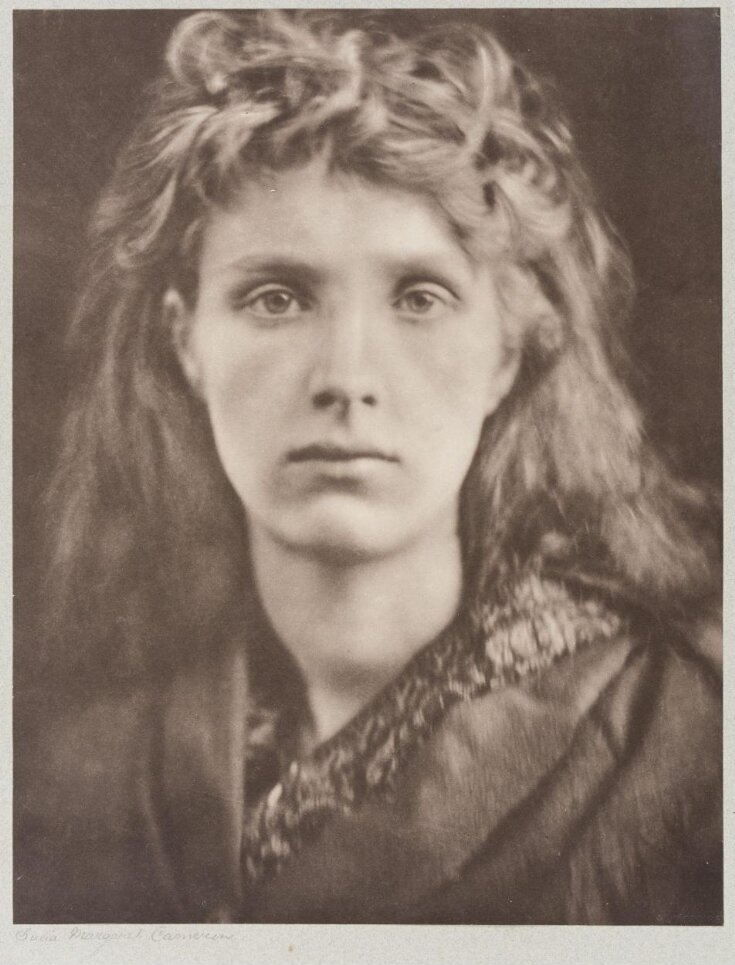

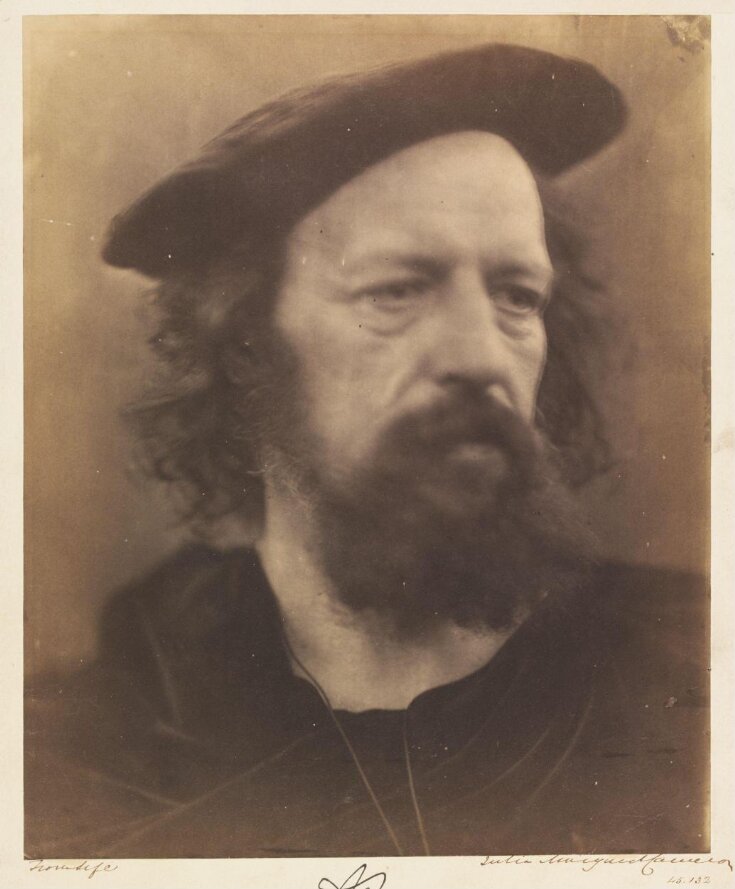

Her most famous photographs are the portraits of eminent men and women of the age, and here you can see a stark contrast in the way she captured her sitter according to their gender: the women are treated with a romantic sensibility, hair flowing just-so, ambiguous expressions and poses, decorative scenery. They are exclusively young and pretty. The men are older, more stoic, full focus on their faces; a more reverent approach.

Then there is another category of her photographs all together, the allegorical or narrative portraits that tell a different kind of story: children as angels, her maid as the Madonna, scenes from Shakespeare, Arthurian legends. The spectral quality of the hazy light and the way the amateur models subtly imbue the characters with their own personalities or feelings in the moment the photo was taken – make these some of Julia Margaret’s most enduring works. Taking the sitter out of the formal Victorian studio setting and using soft focus as an aesthetic choice is what made her so far ahead of her time.

I love that rural little forest village––where I spent my formative years playing pool and blasting Patrick Wolf songs on the pub jukebox, in-between reading Descartes and discovering surrealism and making the best friends of my life––and feel quite proud of the way it is a part of Julia Margaret Cameron’s story too. Her gift to the railway was a token of appreciation for kindnesses shown as she waited for the London train which carried her son home; they would then make the onward journey together from Brockenhurst to Lymington and across the Solent to the Isle of Wight, past the Needles and into the little bay at Freshwater, where her house has been kept as a museum dedicated to her legacy. It makes me feel closer to her to know she passed through these places which make up such a part of my own identity. It was at Brockenhurst station that one Helmut Gernsheim, the distinguished photographic historian, happened upon Julia Margaret’s work for the first time in the mid-twentieth century. This ignited something of a ‘rediscovery’ of the artist, propelling her into the public consciousness once again, where she absolutely deserves to stay.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?