Read Time 9 minutes

Female collectors: Dawn Parsonage’s found photography

‘Lots of people are quite unusual or have these funny moments … we haven’t invented comedy or humour over the past 30 years, people have been funny since the dawn of time and photography has been capturing that since the 1850s. We’ve not changed, we’ve just not been able to celebrate it.’

The year was 2016 when I stared, mesmerised, as Dawn Parsonage walked onto the stage of The Wheatsheaf in Oxford, hunched over with arms and legs outstretched like a spider. She was some kind of goblin, performing with The Oxford Imps. I was lucky enough to play several goblin-like characters with her over the next couple of years, kindred spirits in our fundamental oddness. Dawn’s ability to see the heart and the humour in the absurd and the ugly serves her well not only on stage, but as a collector of found photography.

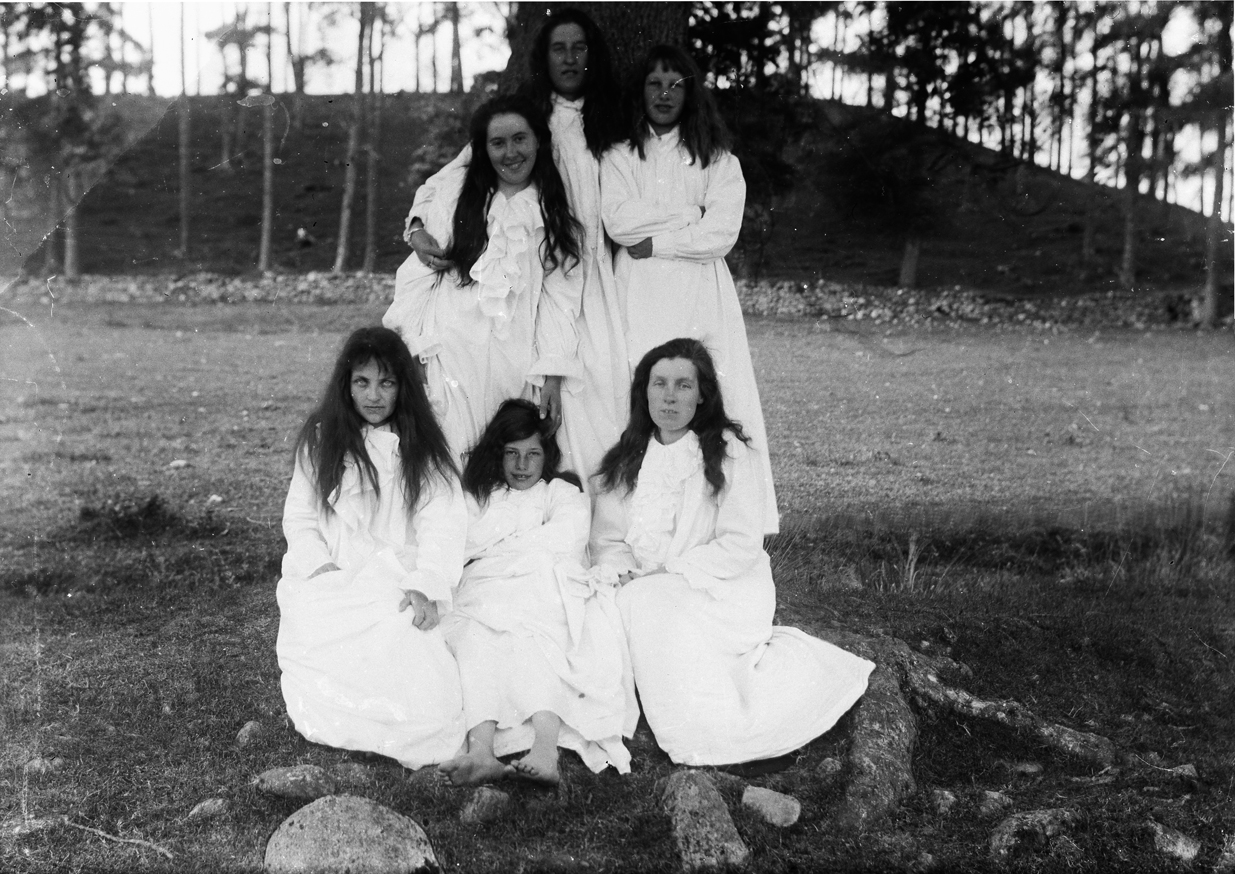

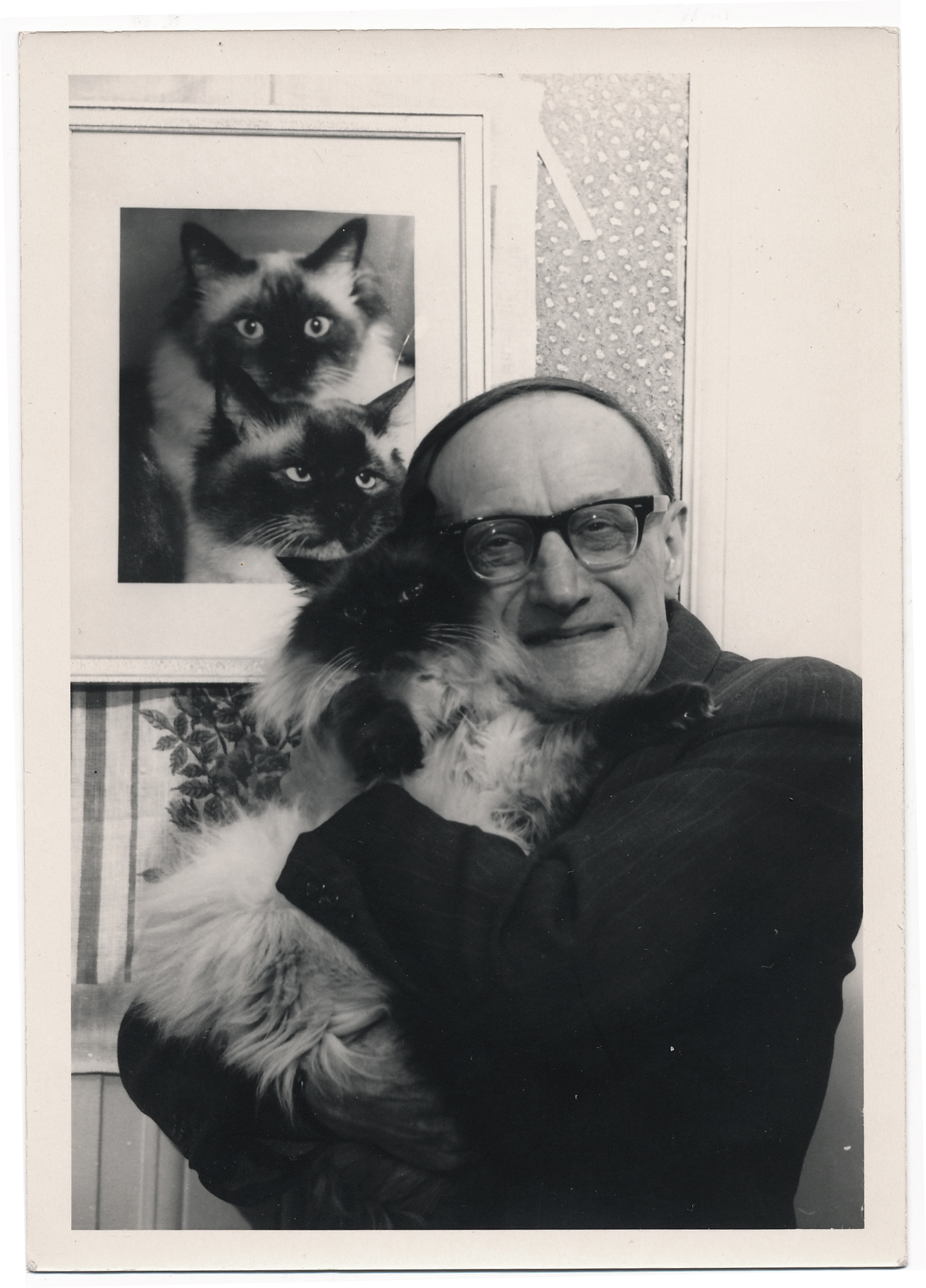

Several years later I left Oxford and sublet Dawn’s room in London, and had the unique opportunity to live amongst a small selection of her collection: over 10,000 found photographs and photography paraphernalia. I remember there being several Victorian figures tacked to the walls who watched benevolently down on the bed, and a shelf filled with photographic reference books and Bread’s 1977 album ‘The Sound of Bread’ which made Dawn laugh. It was fabulous. Dawn has been collecting found photographs––including negatives, colour processes, and slides––for 30 years, starting when she was a pre-teen. She has shared highlights from her collection on her Instagram page @foundphotouk since 2015, including a handful of scanned slides of my family in the 1970s that I gave to Dawn when my grandmother cleared out her attic. The account has amassed an engaged following and features brilliant images: a dog with uncannily human eyes, Edwardians rehearsing for a play, and world war one soldiers posing with a skeleton in a macabre family photo.

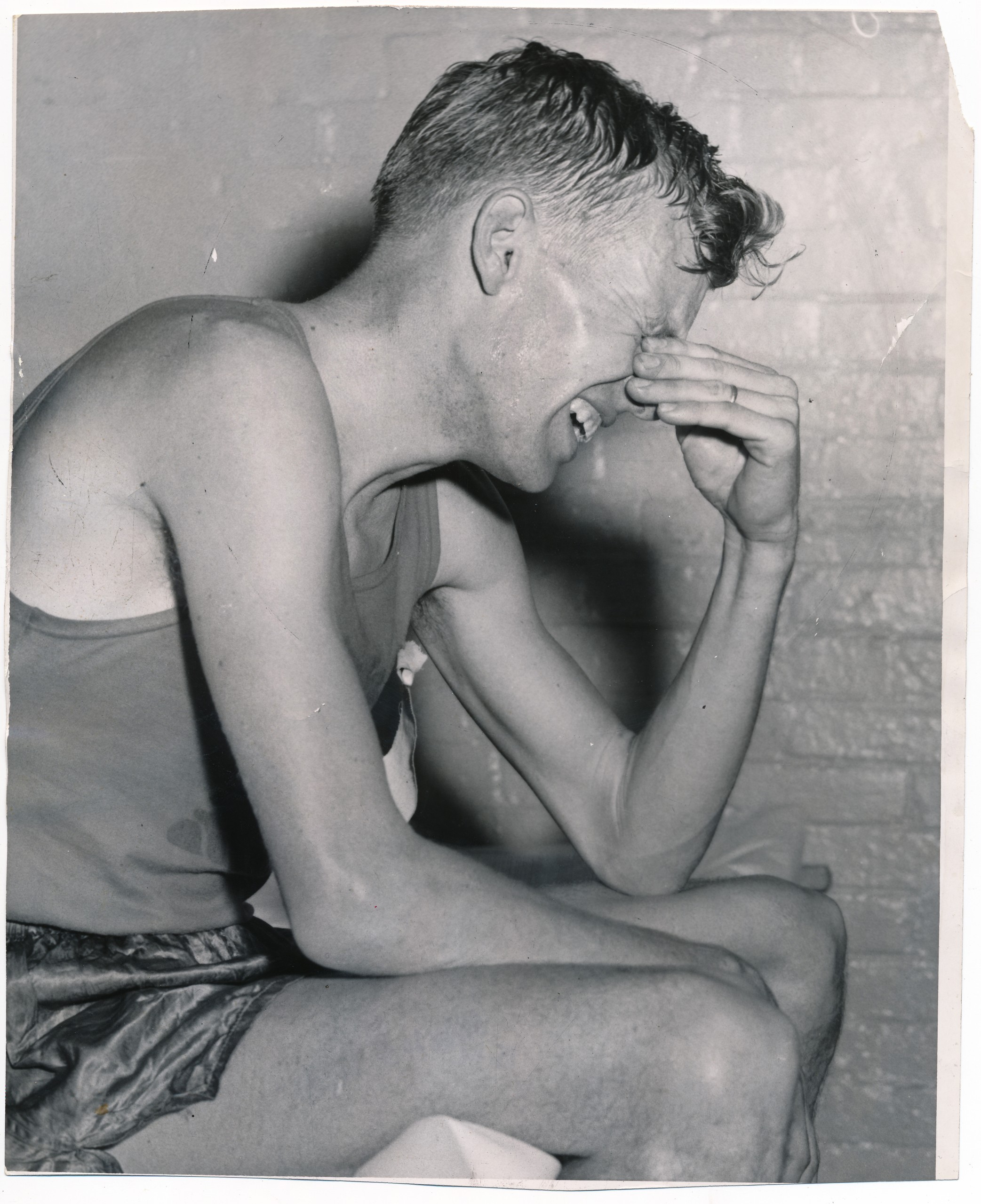

Speaking to Dawn, the raison d’être of her collection is to capture the emotions that are warped or erased by the presence of a camera. The stern-faced images of Victorians make us believe they were inherently stern people, rather than three-dimensional, funny, emotional folks who were forced into an embarrassed formality by having their photo taken. [The expense and social pressure of having one’s photo taken, prolific tooth rot, and, early on, the slow-shutter speed which meant that poses had to be held for up to several minutes, meant that being in front of the camera was not a casual affair.] We’ve all been there – happily engaged in conversation at some birthday party or event, and suddenly we see a camera pointed our way and we adjust our posture and smile with our mouths closed. ‘It’s like a forcefield’ said Dawn.

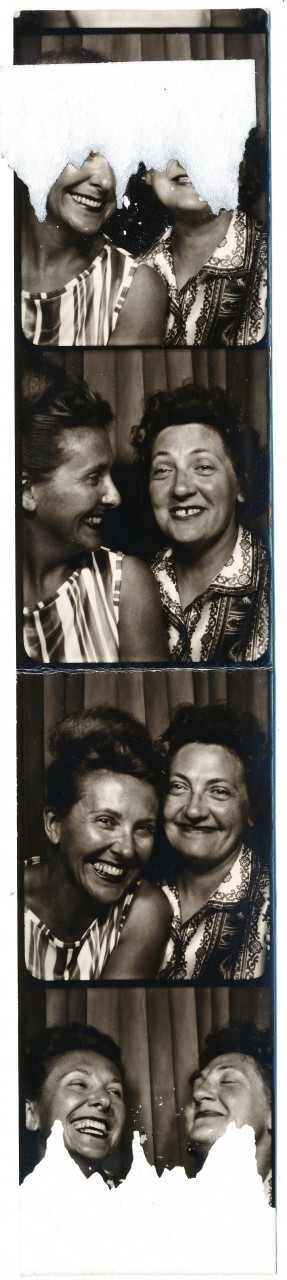

Dawn’s collection is data in her research into ‘how people capture images without being overly influenced by the camera’, fascinated by the instances where emotions are captured in a raw way, unchanged by the presence of the camera. It is made up of amateur photography, accidentally taken images, images taken in secret, and photos taken by family members and friends. The informality of how these photos were taken meant that vulnerable and raw moments could be captured authentically. She explained that found photographs are the best place to find these captured emotions, because they are often the ‘drafts’ thrown away in the place of a formal final image, or come from family albums where the mood is more relaxed and the subjects are at ease with the person holding the camera. Dawn respects images that have been visually neglected – ‘old photos are covered with a terrible blanket of nostalgia, or cuteness, or fodder for craft projects’ and her role is to bring attention back to their value as artefacts of human lives. Her collection not only empowers these photograph’s sitters, but celebrates the importance of photography in everyday society and champions those behind the camera.

Dawn recounted to me the very first album she collected, aged around 13 at a flea market in her home city of Oxford, which she found on a bric-and-brac table in the rain. ‘I opened it up and it was this woman’s life’. Dawn’s sense of injustice at the album’s neglect was acute, and she was immediately filled with a new passion to find and preserve these forgotten photographic treasures.

Since then, she has keenly attended car boot fairs, auctions, and rummage sales to find images that capture the real human experience. She told me about a series of glass negatives taken in Scotland at the turn of the 20th century which she found, showing a family of budding photographers taking images of each other and in their dark room. One of the daughters is captured in many images dressed in men’s clothes. Dawn sounded emotional recounting quite how much love there was in these photographs. She also praised war photography because ‘there was nowhere for egos – they were just real.’ Her collection––stored in her St Leonards studio and digitally scanned––spans from early Victorian Daguerrotypes to modern shots taken on disposables, but what they all have in common is that emotional realness.

Dawn has travelled across the globe attending collector’s fairs, but it is clear that she considers herself something of an outsider collector, and that her collection of ‘small snapshots and negatives’ is often dismissed by the more typical collectors who do it for prestige and value, rather than some emotional mission. She told me that ‘some of the slightly old-school folk don’t get it’ and at one convention she was asked if she had come to the wrong place. These collectors purchase photographs by big-names, and are confused by Dawn’s collection of magic lantern slides, anonymous snaps, and discarded filters.

Her collection was, already, not what the established photographic community expected, so Dawn took it one step further and began sharing her images on social media. She explained that some in the community were very encouraging of the collection, if initially surprised. While she has formed great friendships in that world, she was been met by discouragement by some ‘old men’ who believed that ‘if you have a thing that you want to grow in value you shouldn’t share it … but I’ve never believed in sitting on my collection like a dragon on gold, I’ve always wanted to share it with as many people as possible’. She has many wonderful stories of the audiences she’s reached, who respond to the social historical element of the collection. One incredible story of reconnecting people with their history came when Dawn shared an image of a town in the Congo in the 1930s, and she managed to find the street in which the image was taken via Google Maps. Someone from the town messaged Dawn, thanking her for finding and sharing the image, as their community did not have any images of their town before the Crisis conflict in 1960. She describes her Instagram as a ‘proper forum’, with viewers from across the globe.

‘What I hope is that people will realise the art in what I’m doing, because there’s a lot of people who collect found photography who manipulate the image to create ‘art’ – but I want to present the image, that I found among millions of other images, present this to people and say “hey, look at this!”‘ Curating her collection, sometimes blowing the images up large-scale, is a key part to the artistry of Dawn’s practice, and several of her found photographs of people looking bored were enlarged and included in her Boring Exhibition in Bermondsey Project Space in 2019. Dawn’s role seems to be a translator for these images, advocating for their visual value – like an artistic alchemist.

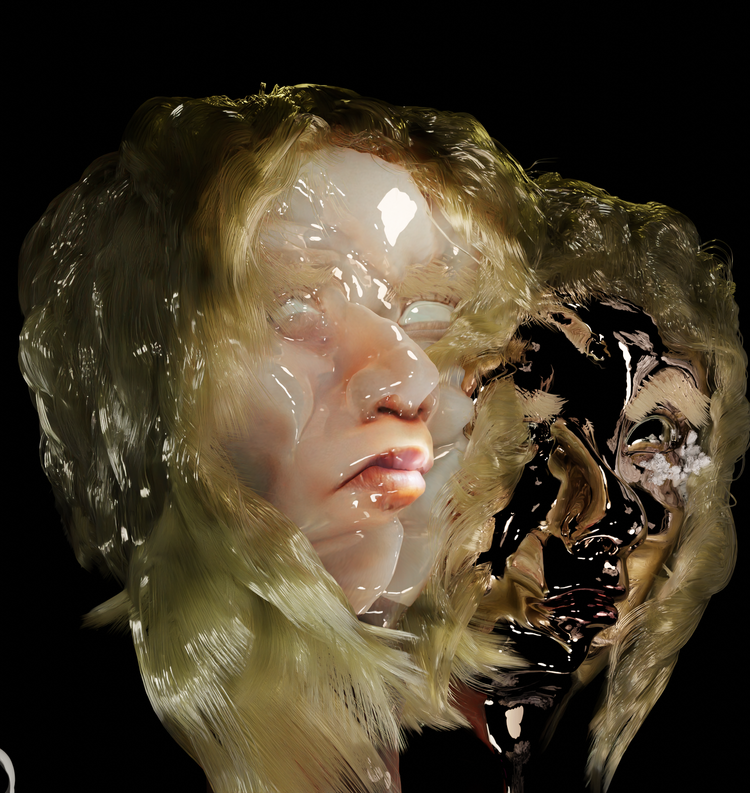

Dawn is a photographer in her own right, taking her own images and working as an art director for Light Space Color with partner Peter Hudson. She tells me about her two latest projects, the first titled Unfamiliar, which she took during lockdown, experimenting with intense colour filters, and the second a single roll of film she has taken over the last year, capturing her newly born daughter. ‘They feel very authentic to my experience over the last year… they’re full of––to me––the essence of that year, meaning they’re not always perfectly crisp’, a quality which Dawn celebrated. She explained that even the work of a great master like Diane Arbus isn’t necessarily in full-focus when you blow it up, as you can see in exhibitions of their work. ‘That’s the journey I will continue to be on… I keep searching for how to capture raw emotions.’ In her own practice as with her collection, Dawn’s mission is like that of a magpie; to look at life from unusual angles, and to find hidden, discarded, or misunderstood treasures and to bring them to her audience.

END

All photographs courtesy of Dawn’s collection. See more here.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?