Read Time 8 minutes

Historical Heroines: Diane Arbus’s Halloween crowd

During the time Diane Arbus was moving away from co-creating fashion editorials with her husband to adopting what would come to be her signature style of subversive portraiture, she said the following; ;If only Hitler were alive, I’d photograph him–he was the greatest loser of them all.’

It reminds me of when I watched the Netflix documentary Don’t F**k With Cats with a friend and when we’d finished we discussed Luka Magnotta’s conceptual, cinematic––almost high camp––approach to his vicious crimes. My friend said, ‘I wish he’d killed more people,’ then looked embarrassed.

I totally, totally understand the sentiment behind both these statements. I suspect actually that most people do, but there is a dishonest reluctance to admit to it. It’s like the adage of not being able to look away from a car crash, but removing the assumption that in this idiom, the car crash is an accident, rather than intentional, purposeful evil.

There is an undeniable reason to be fascinated by the aesthetics of immorality, the extreme opposite of how we are supposed to live our lives. I agree on an intellectual and principled level why we should take more time and care to honour the victims of Jack the Ripper as women with hopes and dreams and beating hearts, than we do the perpetrator, but at the same time I understand why the main thing people want to hear about was the way the women were disemboweled, the mystery of whodunnit. Sometimes the desire to put an image, a face, to a dastardly act of evil overpowers our impulse to empathise with the human victim.

Of course, Diane Arbus never did photograph Hitler. In fact her sitters weren’t generally close to evil at all.

Evil, no, but other, most certainly.

The words associated with her documentary work, ‘grotesque’ and ‘freakish’, come from a mid-twentieth century parlance that characterised the intolerance of that era. It’s easy to marvel at how far we’ve come as a society, now that the vocabulary used to describe the marginalised is a constantly hot topic, and what is appropriate in language is frequently debated, refined, and finessed. But the truth is that Arbus’s photographs still make us uncomfortable to a degree.

There’s always an inevitable moral maze of QUESTIONS that come with reflecting on Diane Arbus’s work. Are the photographs exploitative? Condescending? Voyeuristic? She would have argued that she was no more voyeuristic than any other photographer, and I would argue probably much less exploitative than many [paparazzi come to mind here]. What she did do though was capture a tension between the normal and the abnormal.

‘How ordinary is a charming pair of twins,’ she said of one of her most iconic and enduring photographs. I had three sets of twins in my class at one point in primary school, so yeah, pretty ordinary stuff, but then why is there something so unsettling about this picture? The composition, the pose, the black dresses with white collars are so simple, so very ordinary, but it’s fucking disarming nonetheless.

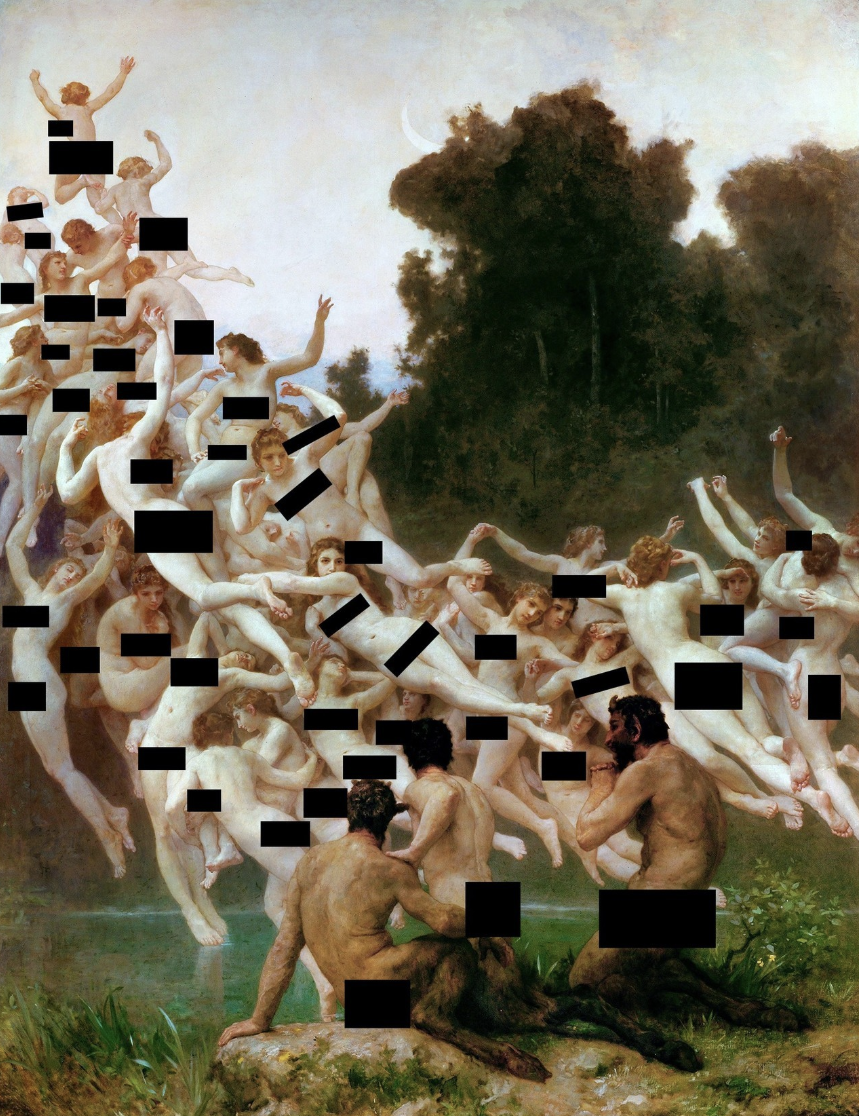

So too are Arbus’s other portraits, a catalogue of misfits who at that time lived on the fringes of society. I read that visitors to a MoMA exhibition featuring some of her photographs actually spat on her work mounted on the walls, so revolted and disturbed were they at seeing people who usually were so easily ignored by the bourgeoisie, showcased as art, in an art gallery. Self-styled freaks, bearded women and tattooed men, drag kings and queens, people with dwarfism, nudists, sex workers, disenfranchised teenagers hanging out by the piers, all in some way marginalised, but yet captured by Arbus’s lens. Susan Sontag noted Arbus’s affection for whom she dubbed ‘the Halloween crowd’.

Diane Arbus is part of a legacy of photographers and artists preoccupied with the disenfranchised; Lisette Model, Weegee, Robert Frost, and Brassaï at various points undertook similar work, and she was influenced by August Sander and Alfred Steiglitz, too. But I’ve been thinking about why Arbus is the poster girl for this type of photograph. In my view, it largely comes down to what the purpose of her work was, which, I think, was far more about exorcising her own demons about her place in the world, stimulating her own pleasure points by way of risk taking and entering into a perceived danger zone, than about making a larger statement about society and social class.

In many ways, I don’t think her work was ever really about the sitters, but about herself and the adrenaline she got from walking into the unknown and the uncomfortable. I guess in this sense the pictures are exploitative to a degree. However, this also contributes to what makes her work so wonderful – instead of remaining removed from the photograph and anonymous to the subject, as did some of her contemporaries exploring similar themes, she was THERE. She developed relationships, made herself a part of their world, even if for only a fleeting moment. She, and her unique way of seeing, are the magic ingredient.

It’s ironic that those aforementioned terms [grotesque, freakish etc], would be far better applied to the world that she was trying to liberate herself from. Diane Arbus’s New York is the polar opposite to that of, say, a Blair Waldorf character – but on a superficial level Arbus had far more in common with that well-bred, capitalist, money driven society than the underworld she preferred to depict. She grew up in The San Remo apartment building overlooking Central Park – other residents over time include Rita Hayworth, Bono, Tiger Woods and Diane Keaton, the residents board did however reject Madonna [fools] – and her family ran the Fifth Avenue furrier and department store Russeks. Her upbringing was pampered and gilded, and project managed by nannies, maids and chauffeurs. Quelle grotesque.

The spoiled rich girl rebelled––it was ever thus––and married Allan Arbus at age 18 having dated him for four years, and together they embarked on a fairly hand-to-mouth existence in image creation. It’s a tale as old as time, but I do find Diane’s particular rebellious MO amusing nonetheless; exclaiming proudly to an all-male studio team in the 1950s, ‘I’ve got my period!’ is fab.

Diane Arbus speaks to a hunger to observe the other that I think sits in all of us. In a time that is ostensibly more inclusive and tolerant yet simultaneously becoming increasingly gentrified, her work still stands as powerful today as it did in the context of the 1950s-1970s.

It’s hard to get under the skin of Arbus as a person because of her ethereal, introspective, lonely, awkward, and often paradoxical nature. But it’s this nature that permeates her photographs and her legacy, and holds my gaze, even when the photograph in question is of something as challenging as a decomposing corpse, or a slaughtered pig, or something as mundane yet extraordinary as children sat on a stoop wearing monster masks. It’s their humanity, I think, that makes these pictures so great.

END.

All artworks by Diane Arbus.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?