Read Time 5 minutes

50 years of Ways of Seeing

Half a century on from when the hit TV series first premiered, Ways of Seeing remains a stalwart in arts education. What’s the reason for its longevity?

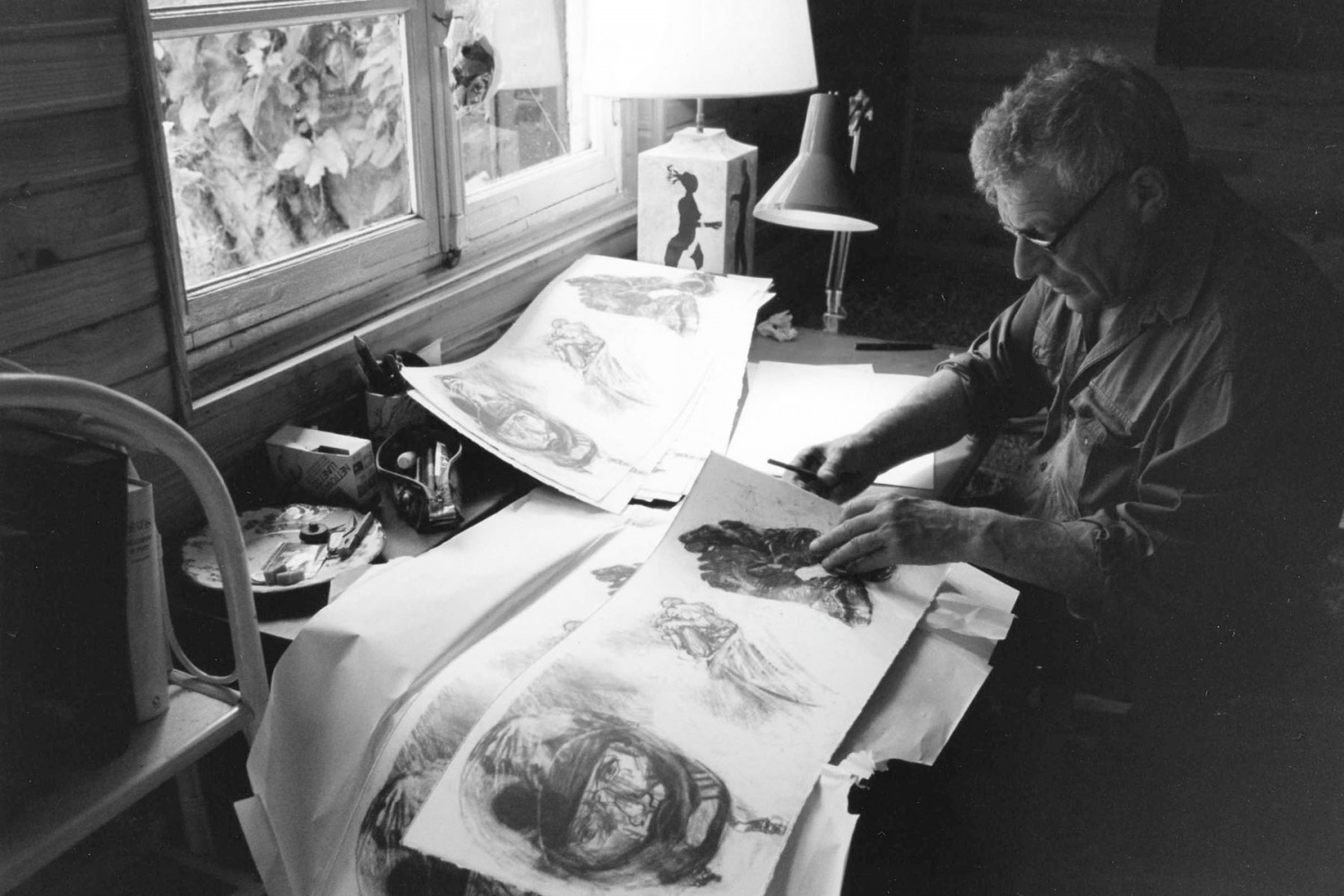

Fifty years ago a man – handsome in that distinctly louche 1970s way, with floppy hair, jazzy shirt, furrowed brow and Leonard Cohen mouth – stood in front of a blue screen and, gazing pointedly into the camera, taught the British public the myriad ways their eyes might be used, and how the things they saw might be interpreted. The man was John Berger.

Berger, who died in 2017, was the ideal master of ceremonies. An art critic and cultural theorist that you could really get behind; feminist icon and quietly socialist king, never weaponising his own intelligence, never patronising, always happy to defer to the opinions and expertise of others, especially the children whose purity of vision and clarity of interpretation made them the perfect counterpoint to an art industry steeped in jargon and mystification.

Mystification. This was the crux of the matter that Ways of Seeing sought to unravel. In four half hour episodes and an accompanying book of essays––some written, some pictorial––Berger and his collaborators [Mike Dibb, Sven Blomberg, Chris Fox and Richard Hollis] advocated for an understanding of Western artistic tradition that put the general viewer at its heart; accessibility was the key, demystification was their mission.

To examine Ways of Seeing in 2022 is to be struck by how prescient its ideas remain. Berger touched upon themes such as colonialism, the objectification of women and the male gaze, class divides and power struggles, ownership and commodification, capitalism and patriarchy. If the language is at times skewed toward the heteronormative, it’s because, well, so was the art.

Berger is clear from the off about the limitations and exceptions to his argument, and does not attempt any kind of universality in the overall message. Non-European art is brought into the conversation to compare and contrast, but ultimately his agenda is to inform the British public about the kind of oil paintings they are the most likely to encounter, whether at say, the National Gallery, or in reproduced versions at the gift shop – in other words art produced almost exclusively for a white European elite.

The longevity of its modes of critical evaluation, and the conclusions it reaches, is what makes Ways of Seeing remain such a fundamental textual study in arts education today. Its concern is the WHY as well as the HOW. Traditions in oil painting may be the backbone of the series, but Berger also explores new mediums too, namely photography as a publicity tool. Artists and advertisers alike often attempt––with varying degrees of success––to tear up the rulebook and disrupt the status quo of the way things are done, but ultimately the devices are often the same ones explored by Ways of Seeing. Art and capitalism remain inextricably linked. Advertising still sells by way of envy or threat [or both]. Ways of Seeing teaches us what the rules are, and crucially, gives us something to rebel against, a boon to any student of visual culture.

Ways of Seeing teaches us what the rules are, and crucially, gives us something to rebel against, a boon to any student of visual culture.

I asked my parents for a bit of background on what a standard arts education was like in the primary and secondary school systems during the early 1970s, and the answer was overwhelmingly practical. More like how to do, than how to understand. Whilst they may have been able to experiment with watercolours, or even explore anatomy by way of life drawing, the theoretical frameworks and semiotics of art were off limits, and, according to my parents at least, to be interested in art in a high minded sort of way would have been considered deeply poncey. Inevitably class and education status come into play here, but according to Ofcom by the 1970s approximately 93% of households either had a television set, or had access to one, meaning that broadcasting a show like this meant beaming its message into the mainstream. What’s more, the man delivering said message was not a stuffy, suited, museum type, but charismatic, cool and––okay I’m just gunna say it––goddam fit n sexy.

Above all Ways of Seeing proffered a call to scepticism that transcends our dialogue with art alone. Its host encouraged the audience to analyse rather than blindly revere. To question everything, not just the way we interact with images but the way they interact with each other, with accompanying text, with the world. To not take things at face value. While the lessons taught by Ways of Seeing have an application beyond imagery, in a world of filters, NFTs and deep-fakes, an ability to habitually scrutinise imagery and visual culture does seem like a pretty good place to start, and thus Berger’s lessons endure.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?