Read Time 8 minutes

Historical Heroines: Claude Cahun & Marcel Moore, two halves of one whole

Photographers, illustrators, essayists, poets, graphic designers, mixed-media artists, Communists, resistors, activists, performers – no small number of monikers for two women in the first half of the twentieth century to achieve.

When we first began discussing the possibilities of subject matter for this edition in the series Historical Heroines, we only ever discussed the name Claude Cahun as a singular entity. In the intervening month or so between pitching Cahun and actually putting pen to paper, I still thought this piece would be about Cahun alone, but it now strikes me as somewhat reductive to write about them as if they were detached in any way, as anything other than inseparable and inextricably connected to their partner Marcel Moore.

And so, I present to you, Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Two halves of a whole identity.

But first, a note on pronouns. I defer to an excellent 2020 zine on the two artists by Livvy Drusilla and Anna George, titled Another Mask, on this matter. In a considered and compellingly reasoned essay on the subject of representing genderqueer identity in a historical context [and in the context of people whose native tongue was the heavily gendered French language], Drusilla and George choose to refer to Cahun using they/them, and Moore using she/her. Their argument for this is sharp and, importantly, inconclusive, but their reasoning makes sense to me and so I shall follow suit.

Due to several crossovers in period, geography, sexuality, and artistic ambition, Cahun and Moore can be associated with various subsections of the avant-garde scene in 1920s and 30s Europe.

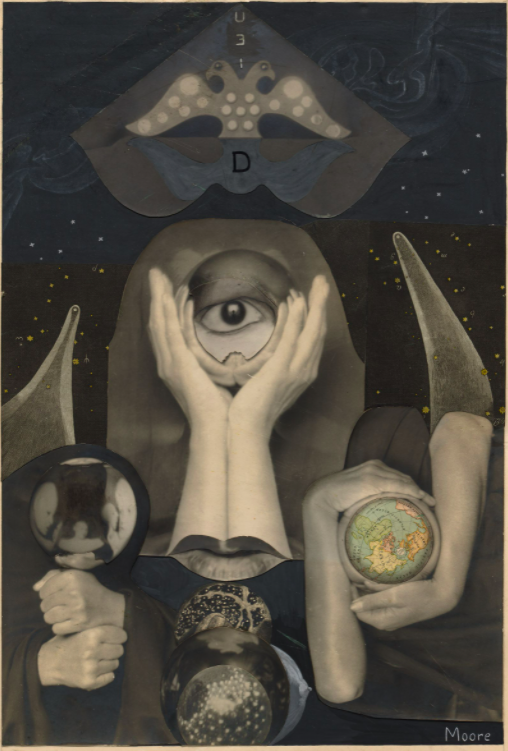

Their same sex relationship and Cahun’s adventurous and experimental writings point to a kinship with the modernist, lesbian literary circle which included Djuna Barnes, Natalie Barney and Shakespeare & Company’s Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier [the latter of whom crucially refused to support Cahun’s 1930 text Aveux non avenus, or Disavowels].

There is a natural affinity with the Surrealists, despite disputed misogynist Andre Breton’s best efforts to exclude those who weren’t men from the movement. He was, it is said, an admirer of Cahun’s talent, but wary of them as a person – they did however maintain a lasting friendship with his wife, Jacqueline.

Their relationship both in art as in life was as crucial as oxygen

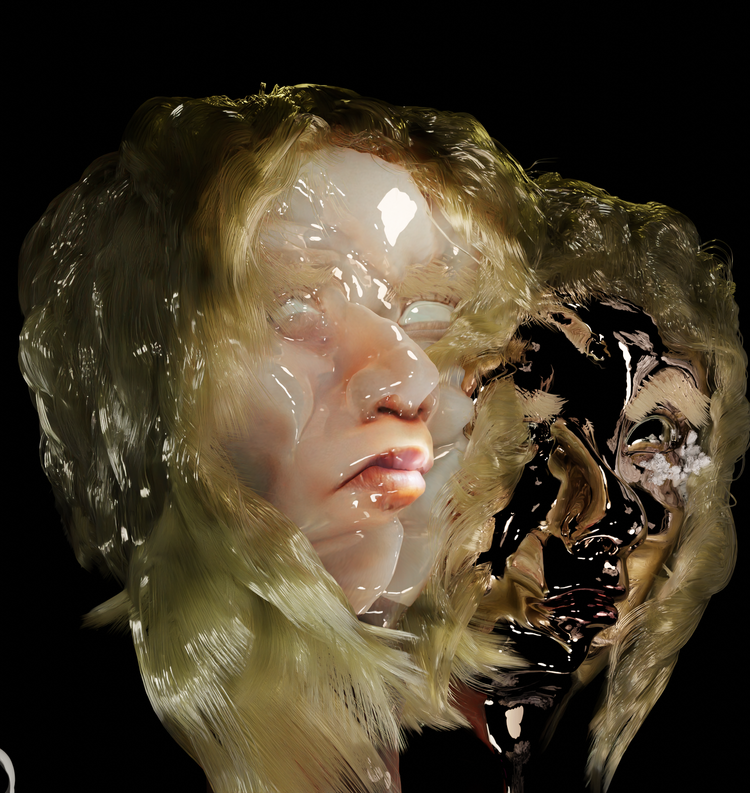

Then, there was the world of theatre, whose influence cannot be understated when examining their oeuvre of photography and photomontages. The theatrical goings-on in interwar Paris provided rich fodder for practising artists to draw from, and Cahun and Moore’s frequent use of masks and other shapeshifting costume, as well as compositions that echo the complexity and illusionary qualities of stage sets indicate a close accord with this world.

Moore’s illustrations share strong ties to fashion plates from the time, but hers is not a name that ever seemingly crops up when looking at the history of fashion.

None of these groupings feel like an entirely easy fit for the two artists. They are at their most comfortable AND exciting when they are absorbed only with themselves and one another. This is kind of what I love about them, in the context of their day they created independently from other movements and made work which would lay the foundations for the future of art exploring queer identities. It is the romantically minded introvert’s fantasy.

They walked their cats on leashes together, sunbathed naked together, resisted Nazi occupation together, were arrested together and sentenced to death together

Even in photographs that Cahun clearly couldn’t have physically taken without the help of another pair of hands, they are often attributed as the singular photographer with little recognition of the collaborative nature of their relationship with Moore. Many misattributions are positively unforgivable. Some of the collages which illustrate Disavowels are actually signed by Moore and yet her name does not even appear on the blurb of the English translation. Tirza True Latimer’s excellent lecture on this subject is available on YouTube, and it’s a good watch.

Latimer believes––as do I––this repeated oversight is largely a product of an art world [and society tbh] that prefers to recognise singular genius and sees dual-effort as somehow, inexplicably, less effort, but it’s notable that the same treatment does not always get metred out to heterosexual couples who practise together. Contemporary curators and writers are keen to redress the balance in recognition and give long overdue credit to women overshadowed by their male partners throughout history, yet in a lesbian relationship this imbalance in credit is not so readily fixed.

Yet for Cahun and Moore, their relationship to one another both in art as in life was as crucial as oxygen, as natural as breathing. I don’t believe there would be a Cahun without a Moore. Cahun likened meeting Moore to lightning. They were teenagers when they met and their reciprocal passion was instantaneous. Eight years later, in 1917, Cahun’s father married Moore’s mother and they legally became stepsisters [?, but it allowed the two women to live together in a way that was far more socially acceptable than just being straightforward about the true nature of their relationship].

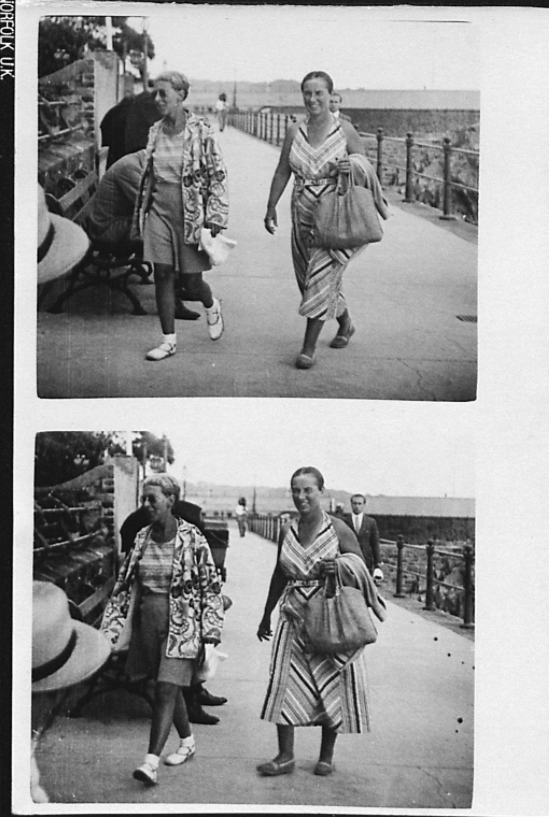

From 1908 to Cahun’s death in 1954 they lived together––first in Nantes, then Paris, then Jersey––created and published together, walked their cats on leashes together, sunbathed naked together, resisted Nazi occupation together, were arrested together and sentenced to death together.

One of my favourite stories about Cahun and Moore comes from when they were charged for their monumentally largescale acts of resistance during the Nazi occupation of Jersey – they made so many artefacts of anti-German propaganda, as small and delicate as a handwritten message on the inside of a cigarette packet, as time consuming and inventive as photo montaging an entire magazine of images, that they were assumed to be part of a huge network of coordinated resistors. That it could all be the work of two women in their fifties was inconceivable. For the crimes of listening to the BBC, owning a camera, and distributing anti-Nazi propaganda they were sentenced to a prison term, and execution. Cahun stood up in court and asked wryly, which of the sentences they would be serving first.

Theirs were lives defined by quiet rebellion through artistic practice and tender defiance.

I love how enigmatic they remain, even as their oeuvre becomes more widely celebrated with the passing of time. Moore’s legacy suffers from underexposure and for being the less photographed of the two, but even Cahun whose distinctive androgynous face is the subject of so much of their work is something of an unknown. There is this fabulous disconnect between the Cahun we see in the 1920s––shaved head, sharp features and small, defiant mouth––to the Cahun of the years surrounding the war. Here she is far more typical, even ordinary, with coiffed hair neat under a head scarf, like she wouldn’t be out of place at Balmoral. I really love these late portraits, which are of a woman in the final phase of her metamorphosis, revelling in her own mystique.

The 1920s and 30s were a time of real social change for Europe, when unconventional lifestyles and subversions of the norm were celebrated and capitalised upon [until, famously they weren’t], and yet Cahun and Moore’s rejection––or perhaps, isolation––from their contemporaries illustrates a real tension in just how unconventional one was allowed to be.

And even for me now, as someone who suffers from real Golden Age Thinking about the Paris avant-garde, I find myself so drawn to the quieter Jersey years in the lives of these remarkable women. For all the glamour and sex appeal of the former, there is something utterly romantic about the latter. They lived the dream of a productive and creative urban adolescence followed by an escape to a tranquil seaside idyll [although my similar fantasy does not include an occupying fascist force lol]. It wasn’t a life without hardship or pain, but this, along with intensive exploration and analysis of the self, was turned into a productive output, one which at long last is being enjoyed and examined the way it deserves.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?