Read Time 8 minutes

Historical Heroines: Lee Miller, the hot girl of surrealism

The present owners of 21 Downshire Hill may have cause to wonder who the mysterious stranger, so often seen lingering outside their house, could possibly be. The house itself is typical of the area, although not the biggest or grandest on the hill it is handsome, made from smudgy, oatmeal-coloured brick, with large windows and elegant wrought iron balconies. It is well positioned between Hampstead Heath and Hampstead proper, with its delis and cafes and very, very rich people. The fact that this terrace house was once occupied by leaders in the fields of art and photography is also fairly typical. Hampstead has long been home to creatives and intellectuals, bohemians, spies, artists, poets, radicals, musicians and, my personal fav: champagne socialists.

Anyway, needless to say, the mysterious stranger is me. And here’s why.

21 Downshire Hill is one of three addresses the American-born Lee Miller lived in during her extensive time in the UK. One, in Kensington, is, for whatever reason, seldom mentioned in books on Lee’s life [I found it in the intelligence report kept by MI5 and the Foreign Office on Lee’s suspected communist sympathies, which I occasionally browse in the early hours, as one does]. The other is Farley’s Farm in East Sussex, which is maintained by Lee’s son and granddaughter and kept as an open house, gallery, and sculpture garden – a shrine of sorts to this incredible woman. Farley’s Farm is Lourdes in the ultimate Lee Miller pilgrimage, but Downshire Hill has the Blue Plaque, and for a London girl with no car it’s the best I can manage.

I feel like ever since I first discovered Lee my life has become about her. I collect pieces of her like a squirrel collects acorns. I genuinely think about her every day.

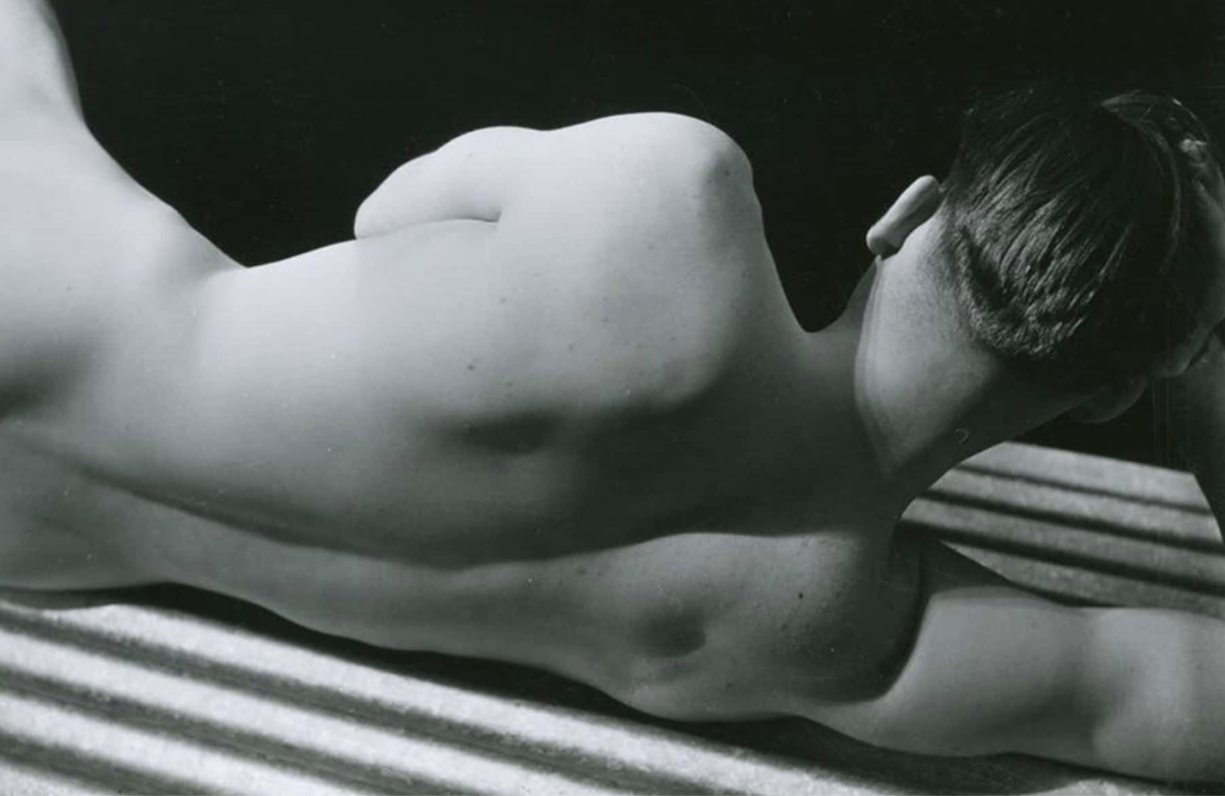

[© Lee Miller Archives England 2015. All Rights Reserved. www.leemiller.co.uk]

I feel like ever since I first discovered Lee my life has become about her. I collect pieces of her like a squirrel collects acorns. I genuinely think about her every day.

There are the books which make up the physical manifestation of my obsession; I own seven with her name in the title and far more where she appears somewhere within the pages. There are places I know she’s been; Lambe Creek in Cornwall, Rue Campagne-Première in Paris, The Freemason’s Arms in Hampstead. I go to these places––when possible––just to feel near her.

If you set your mind to becoming a Lee Miller quasi-scholar then be prepared, for there is a lot of ground to cover. Not only was she the Hot Girl of surrealism, in her seventy years [1907-1977] she established herself as one of history’s truly interesting women. As a photographer, a photojournalist, a model, a muse, sometimes a writer, once an actor, a cook, a hostess – you could pick any one of these areas of her life and be met with an abundance of brilliant anecdotes ranging from the glamorous to the haunting.

Lee’s story is one of serendipity. Myself a rigid, repressed, planning, budgeting, batch-cooking square utterly devoid of spontaneity, I aspire to a life so much dictated by chance. Her modelling career began when she was pulled out from the path of an oncoming car by a man called ……… Condé Nast. A ridiculous moment of good fortune. Said career ended, prematurely, when her portrait was used for a Kotex advert and suddenly she became sanitary towel gal, and nobody wanted sanitary towel gal to advertise their haute couture. While she was working with Man Ray she discovered the technique with which HE would become synonymous, when a mouse ran over her foot in the darkroom and she freaked out and turned the lights on for a moment, creating a kind of halo effect on the photographic paper known as solarisation.

Surrealism was a thread that ran throughout her life in both artistic and personal terms. Even where one might expect a more matter of fact approach – her documentary work capturing the immediate aftermath of WW2 for example – the work is imbued with a kind of wry irony, a dark sense of humour. The same was true of her cooking; who else but Lee would create edible human breasts out of cauliflowers doused in pink mayonnaise, or christen a dish Melted Tomato Thing?

It is hard to convey the depth and, even harder, the impetus for my specific ardour. Regular readers of this series will know I make no secret of my passion for the Surrealists, not least because I think the work is absolutely fucking exquisite, but because the lives and personalities of the key players were so deeply bonkers and punk. But Lee is my numero uno. It would be superficial just to say that Lee is everything I wish I was; radical, accomplished, thoroughly modern, and avant-garde in every respect. It’s true, but it’s deeper than that. There were events in her life that nobody would want for themselves – she was raped at age seven and suffered bouts of gonorrhea. Her body was picked apart and pieced back together by the men in her life through their art [Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Roland Penrose, her father]. She saw first-hand the horrors of The Holocaust.

At the same time, and in the grand tradition of creatives throughout history, these events came to shape her life on every level, and light was born of darkness. The psychiatrist she saw following her rape recounted Freudian theories to his young patient on the distinctions between sex and love, body and soul, and in turn informed Lee’s liberated approach to sexual relationships in her adult life, relationships which led to a lifetime of adventurous travel and encounters with interesting people.

Just as she lent her body to the art of others, she herself created work which questioned and subverted this objectification. One of her most radical photographs, a place setting featuring crisp table mat, silver cutlery, and a plated breast that had been severed from the body in the course of a mastectomy, is a very literal subversion of how these men were using her; pieces of woman to be shared and consumed, appendages separated from the whole human: an eye here, a mouth there. Later, her penchant for cooking was mobilised in response to the artistic paralysis and PTSD she experienced after the war. It must have been traumatic to continue to work professionally in the medium through which she had witnessed such horrors – her camera lens captured humanity at its most degraded – and she abandoned photography in favour of other nourishment: food.

I was extremely anxious about writing this piece because there was going to be so much I’d have to leave out, so much that would have to go unsaid, and no way I could do her proper justice, but I think perhaps this is just volume one of my love letter to Lee, and that over the years new versions will be pondered and transcribed as my relationship with this woman who died 16 years before I was even born continues to marinade and develop and grow. Anyway – it seems impossible to me that a person like Lee could ever die. It’s such an unnatural state for one so curious and absolutely, relentlessly alive. Maybe my love for her isn’t complicated after all, maybe it’s simply that she was extraordinary, and extraordinary people have a way of getting under your skin, and are kept alive that way.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?