Read Time 6 minutes

Historical heroines: Francesca Woodman & changing rooms

We can’t help but read darkness in Francesca Woodman’s eery photographs, however much we’re advised against it. Ahead of The National Portrait Gallery’s show, Portraits to Dream In, which puts her work in dialogue with that of Julia Margaret Cameron, we ponder why.

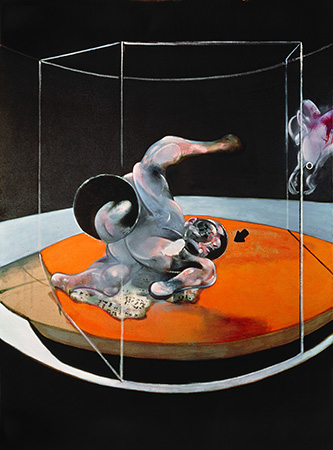

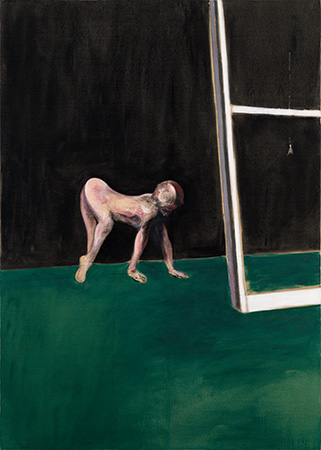

Francesca Woodman’s parents often refuted the common reading of their daughters’ photographs; they believe that they are viewed as sombre because we know that the artist would die young, aged only 22. The images are seen to be prophetic of her suicide. They speak instead of Francesca’s sense of humour, sense of fun, sense of irony. As an artist, she is often compared to her contemporaries, other female photographers, like Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin, but I think her work is more comparable to the paintings of Francis Bacon, where humour and trauma co-exist, and whose work also presents ambiguous spatial relationships.

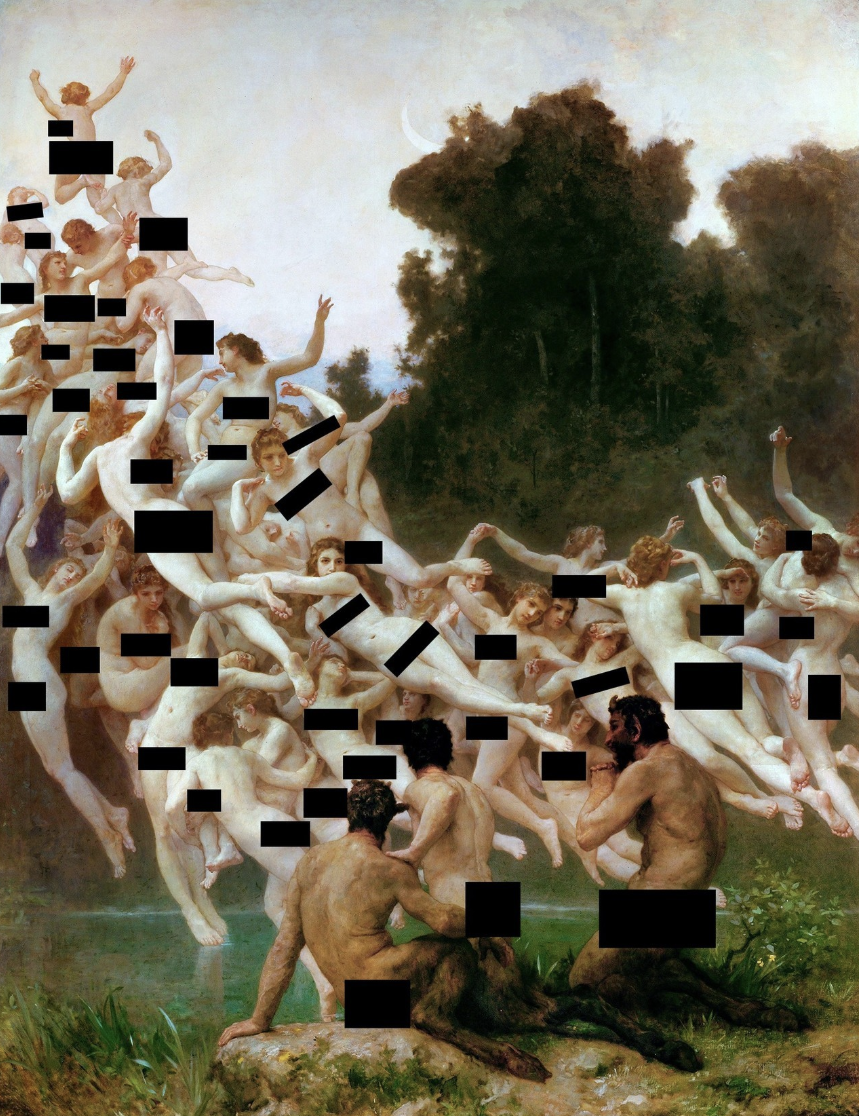

Both artists created distorted tableaux featuring a lone figure in a room – in Francis Bacon’s work this person might be a lover, a friend, a Pope, a figure which blurs the line between animal and human. For Francesca [1958-1981], this person was usually herself. The body is undefined, an imprint, an impression only. The figures are often caught in motion, a dynamic smudge either coming into the frame or just leaving it. Or something else? The relationship between the body and the room is hard to surmise, but absolutely integral to the tenor of the work.

Sometimes when I am waiting to fall asleep I experience a strange sensation; my eyes are closed but I sense the walls of the room expanding, the mattress disappear beneath me, and it’s like I’m floating, alone, in an endless expanse of atmosphere, with nothing in sight in any direction. I used to spend a lot of time on boats, so it’s not an unfamiliar feeling, but it’s somewhat unsettling to feel like the things which contain you are suddenly absent, and you are suspended in space. What’s more unsettling still, is that it’s a sensation I can summon voluntarily.

For me, this strange type of Ganzfeld Effect is discovered on the path between consciousness and unconsciousness, but Francesa’s photographs [and Bacon’s paintings] have the potency of an acid trip, or a Yellow Wall-Paper-esque state of psychosis, where one becomes untethered to physicality. In these examples the person and the room are equally sentient and alive, the walls are at once oppressive––closing in––and stretching outward. Francesca’s art is not sobering because of her own tragic end, but because it plays with the viewer’s grasp of reality. It reminds me of questioning my lucidity. Is it a room or is it a cell, or is it not really there at all? The long-exposures show a lost girl, but maybe the girl isn’t Francesca.

In reality Francesca was a laugh, a precociously talented and self-assured artist with a sophisticated eye who was lightyears ahead of her RISD classmates. They don’t remember her as a tortured soul, but as a person who knew who she was and what she wanted to make. She was raised on art, with artist parents who taught their children that nothing was more of a priority in life than making. She was not as isolated as her photography might have us suppose. A short but rich life: Colorado, college, Italy, New York, family, friends, art.

We tend to search for autobiography within art, particularly in the art of women: Charlotte Perkins-Gilman, who, coincidentally, was also a RISD alumna, suffered from bouts of ill mental health in her life which we might assume influenced the themes of her enduring 1892 novella The Yellow Wall-Paper. Francesca Woodman died by suicide, so her work is almost backdated with melancholia. Francis Bacon, however, is remembered as the glamorous frequenter of the French House, The Colony Room, and other Soho haunts; champagne, sole meunière and gaiety. His life was marked by tragedy too, but his artistic genius [FWIW, I do absolutely classify him as genius] is regularly seen as separate to this, or at least not as a direct byproduct of it. The art stands alone.

Photographs and remembrances of Francesca tell another side to her story, she who lived, not just died. No, for Francesca Woodman, it is important to consider how our own projections mark the photographs. Although, having said this, I do struggle to find the humour in her work; if there’s laughter there, then to me it’s hysterical. I find them stunning but a bit terrifying, haunting, because they trigger some very personal feelings about my relationships with rooms – the way I sometimes dream about the exact texture of the brickwork in my childhood home, the way my comfortability can be dictated by whether the door to the bedroom is open or closed, the way the walls melt away when I’m falling asleep and I find myself bobbing around on nothing at all. It’s not really about Francesca and her truncated potential at all. It is about me, and the emphasis I place on the space I find myself in.

END

All photography courtesy of The Woodman Family Foundation.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, National Portrait Gallery, runs from 21 March – 16 June 2024.

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?