Read Time 6 minutes

Photography & painting: A history

Every few decades a new medium or style breaks into the mainstream and triggers debate amongst creative communities about what counts as art. We’re in one of those cycles now, with AI generated imagery, but pick just about any new thing in the last two centuries and you’ll find the same argument with the same comparisons being made.

Once upon a time it was photography up for debate.

Even during the time when the medium was fighting to be recognised as credible art it was already having a disruptive effect on painting. In fact, it could be said that the invention of photography was the impetus for modern art as we understand it, due in part to painters having to move away from realistic depictions [which obviously photography could do better, and quicker].

Here’s what happened.

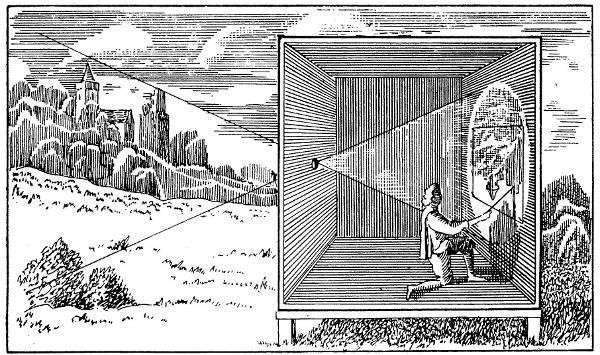

Crazy as it is to imagine, forms of photography have existed as early as the fifth century BC, thanks to Aristotle and his camera obscura. This early technology––if you could call it that––involved the passing of light through a pinhole to get a reflection [in reverse], which could then be traced or copied by painters. This technique was particularly used by landscape painters, and was a fairly common practice right through to the renaissance.

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that things really started to kick off. Initial chemical experiments by Joseph Niepce followed by a fruitful partnership with artist Louis Daguerre led to the first images that we would recognise as photographs in the late 1820s, and by 1833 the daguerreotype had been invented. [Niepce had died suddenly of a stroke, leaving Daguerre to tinker and name the finished product after himself. It’s only recently that Niepce has started to get his flowers as the true inventor.]

It’s interesting to note that although Niepce was an inventor in a fairly general sense, Daguerre was an artist; already well established as a landscape painter and theatrical designer by the time he got involved in the camera game – which means that photography was midwifed into the world by an artist, not just a tech-bro. Even early experiments would have been suffused with artistic considerations like composition and tone, and it was incredibly soon after its discovery that photographs began to feature the stamp of the individual artist, rather than being used merely as a documentary device. Oftentimes this pictorial style was mimicking what the more mature medium of paint could do, but there were those who took it a step further – female artist Julia Margaret Cameron was one of the first to display a unique photographic style with her signature soft-focus and allegorical subject matter.

In its early years photography was not generally perceived as a direct threat to artists, in part because the long exposure time made it impossible to capture things in motion – street scenes with moving carriages or people were reduced to blurs of grey, however when it came to portraiture even the long exposure time was comparatively short. Sitting for a photographic portrait took between 20 and 40 minutes, and was significantly cheaper than sitting for an oil painting, and despite the fact that most painters were of the view that only painting could catch the true essence of a person, by the 1840s there were already 35 photo studios on London’s Regent Street alone.

It was up to painters to use this new technology to their advantage.

The most immediate and obvious advantage for painters was that their work could be reproduced and disseminated in a far more faithful manner to the engravings which had come before [where the artisans made changes according to contemporary tastes, some of which were quite laughably different from the originals they were copying]. Gustave Courbet––whose realist style was profoundly linked to photography––was one of the first artists to commission photo reproductions of his own paintings and he became an early collector of works by photographers like Gustave Le Gray.

Artists were able to paint their human subjects in more complex poses that they couldn’t possibly be expected to hold for long periods of time – simply by taking a photograph as a preparatory study. This led to more adventurous compositions and dynamic paintings than had been seen before; it’s hard to imagine that someone like Degas would have been able to achieve the physical energy of his paintings without photography as a resource.

By the time the 1870s rolled around painting and photography was more intertwined than ever before. The first Impressionist exhibition took place in the studio of celebrated photographer Nadar, who was known for his pioneering use of artificial light. The fact that the studio was fitted with electric lighting meant that the exhibition could stay open through the evenings and attract wealthy visitors on their way to and from the nearby opera house. At the time of this first exhibition the Impressionists were a disparate group, not united by a distinctive style but by a shared independence from the official Academie des Beaux-Arts salon; however Impressionism as we know it today is indebted to the medium of photography, not least for pushing painters like Monet and Renoir to consider new priorities in their work.

There was a healthy exchange between the two mediums which the ‘is photography art?’ discourse belied. Photography gave painters licence to experiment with focus and cropping in their work, and also encouraged them to take a far less literal, realistic approach to capturing the world [although conversely it also allowed painters to capture scenes which they hadn’t actually witnessed with some accuracy rather than relying on pure imagination]. Movements in painting like Impressionism, Cubism, Symbolism, Abstraction and more all owe something to photography, and gradually photography has become a key reference point for artists from Pablo Picasso to Cecily Brown to Francis Bacon [who described the medium as ‘more interesting than either abstract or figurative painting’, and who refused to paint anybody from life].

In turn, this radical progress in the world of painting was also the stimulus for photography itself to quickly become more and more experimental; from the early painterly style to later techniques like solarisation or cameraless rayographs [hello, Man Ray]. Into the twentieth century photography was a key player in avant-garde art movements on its own merits, not just in terms of its proximity to painting, although many artists chose to work in both mediums.

As for the debate about how photography should be categorised, that was answered [at least in an official capacity] way back in 1862, when the question was raised in French court in order to establish photography’s position within copyright law. It was granted the same protections as paintings that year, because if, as it was argued, art = truth + beauty, then photography had already earned its very rightful place.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?