Read Time 7 minutes

The importance of female-run art spaces

To mark our first Darklight& collaboration, with Samantha Picard’s The Art Hang, we reflect on the ways female-led spaces are contributing toward a more accessible and inclusive art industry.

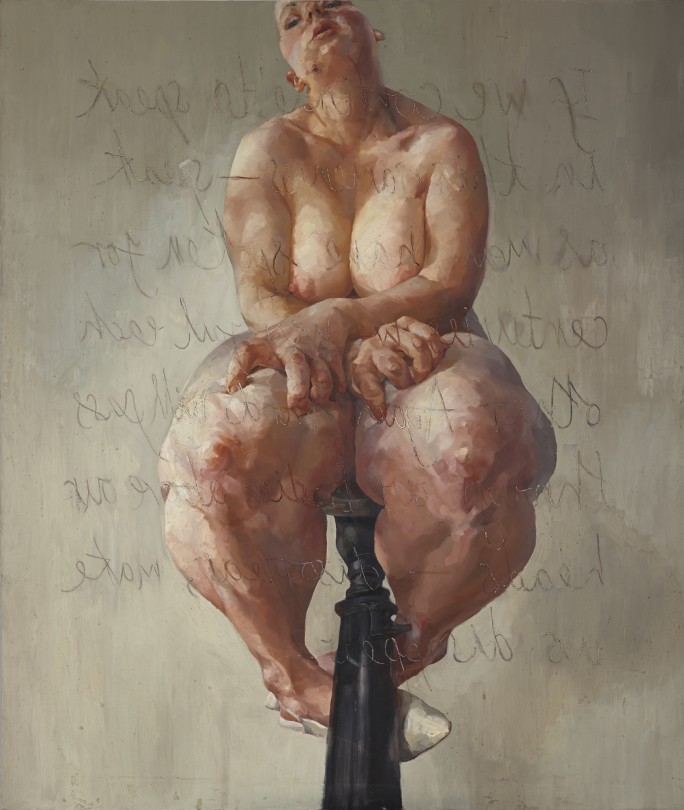

The most highly valued works by female artists, alive and dead, are by Jenny Saville and Georgia O’Keefe respectively. When Jenny Saville’s Propped [1992] sold at auction in 2018 it made history, and yet its $12.4m price tag is almost an eighth of what a Jeff Koons piece sold for only a year later. Considering Saville is lauded as having changed the game for nudes in art, whilst Koons’s creations have been derided and despised by the art world at large, clearly there is something a little off in those figures.

According to Repaint History, the market for work by women has doubled over the past decade, but is still less than the total sales for Picasso alone, and women only represent 2% of the market [but 51% of the population]. Plus, work by female artists is sold at 40% less than that of men. It’s not 40% less good, so what’s that all about?

Work by female artists is sold at 40% less than that of men.

It’s not 40% less good, so what’s that all about?

It was the twentieth century that saw female artists start to get their flowers, albeit in a frustratingly slow and typically unbalanced fashion, FUNNILY ENOUGH coinciding with the time women begun to obtain positions within artistic institutions, or, more often, established and self-funded their own galleries.

The female gallerists, collectors, and patrons of those years may not always have been consciously advocating for female artists––to call them feminists in most cases would be a stretch––but Peggy Guggenheim did host two exhibitions exclusively showcasing work by women, and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was pragmatic in her insistence that women be included in mixed shows. In 1971, Linda Nochlin asked ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ in her seminal ArtReview essay. Today, Nochlin’s provocation is still inspiring modern women to bang the drum for female artists. Founder of The Art Hang, Samantha Picard notes that ‘Fifty years later we still have a way to go. My favourite quote by Nochlin is “In 1969, three major events occurred in my life: I had a baby, I became a feminist, and I organized the first class in Women and Art at Vassar College.”‘

It seems logical that spaces run by women are more likely to be inclusive of work by women and other marginalised genders, which is important for a number of reasons, not least representation. The more diverse the voices are, the more diverse the perspectives will be, and given the impact art has on culture at large this is sure to filter outwards. There must be equity in the means of production, there must be agency, and ownership, and please, there must be parity.

How do these spaces serve the artists? Natalie Christensen, one of three featured photographers showcased in the Darklight& The Art Hang collaboration has this to say: ‘[This has] exposed my work to a broader audience. That is empowering to me! Women’s experiences in the world are very different from men’s, and so what we create will be different. We are connected through a spiritual kinship before even knowing each other and what our individual challenges have been. I think when you start on that foundation, it promotes connectivity.’

Empowerment, connectivity, community, and intersectionality are the primary functions of digital art spaces, and they have the unique advantage of being accessible to almost anyone, almost anywhere. [You’ll note that accessibility and inclusivity are at the heart of both Darklight and The Art Hang, both female-led, both digital]. Optimistically, the success of these online spaces could signify a move away from a creative industry that is only within reach of a very privileged few with an elite address book of contacts. Lamisa Khan, co-founder of Muslim Sisterhood concurs. The collective [that started as an Instagram account] now work on multidisciplinary creative projects both independently and in partnership with global brands. ‘Having digital spaces means that art/creativity can transcend geographical borders and locality, instead allowing for meaningful connection with individuals on a transnational level. It makes a traditionally elitist and nepotistic industry inclusive.’

As in every area of society it’s the Black and brown women, trans women, refugee women, disabled women, and working class women for whom the struggle is most deeply felt, and it’s no big shock that the majority of women who are making the most highly valued work, or directing Western galleries with the biggest budgets are white middle class. This imbalance only reinforces the importance of grassroots organisations; if you can’t get a seat at the table of a legacy institution, or if assimilation is not your bag, then building it yourself from the ground up is a well established strategy – BUILD IT AND THEY WILL COME. Now that can be achieved in thirty seconds just by creating an Instagram. And if the NFT bubble is anything to go by, digital space is valuable real estate, at least for now.

None of this is to say that it doesn’t absolutely suck that mainstream art spaces aren’t more intersectional spaces. It SUCKS that women who are not white, cis, ablebodied and middle class are so often denied the opportunity of walking into a space that already exists, but have to work doubly hard; actually building it first and making it thrive second. And because of the way the world is, it won’t be until a majority of men and white women are working toward the same end goal that anything will have materially changed.

But, in the meantime, will these new-generation spaces present any sort of credible threat to the legacy institutions who dominate, and their often archaic ways of operating? ‘There is strength in numbers,’ says Picard. ‘I think trends in the art world tend to trickle up – if art consumers and younger creatives continue this current [and much needed] outcry about lack of diversity, more established institutions and blue chip galleries will take note and make significant changes in their rosters and programs. Through Instagrams like @cancelartgalleries, which expose stories of discrimination, exploitation, and abuse in the commercial art world, it’s really holding institutions accountable for how they act within, which is just as important as how they present themselves externally.’

Ultimately, until we are able to operate in an artistic [and wider] world that has been totally restructured and rebuilt, the least we can do is try and swing the pendulum in the opposite direction: will with all our might and power to allow female spaces to both survive and to thrive. As Khan says, these spaces in creative industries have a knock on effect in the wider world, by helping ‘Women come together and reject traditional white male dominated art spaces and reimagine the landscape as more equitable and female centred.’ And eventually the reimagining could become reality, non?

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?