Read Time 7 minutes

O Future, where art thou?

When I speak with O Future’s Katherine Mills Rymer I am in late night London and she is in mid-afternoon LA, although you wouldn’t know it was LA at all. The room in which she sits is windowless, almost completely dark save from the light of the computer screen. It’s Katherine’s preferred state. ‘I didn’t want to be the person that was shy and liked to sit in dark rooms like this with no windows. That’s how deep it is. I don’t like light. I sit all day, all the time in a dark room.’ But, fight it as she might –– and coming from South Africa and living in California she really does have to fight it –– sitting in dark rooms has proved fruitful. With her Danish husband Jens Bjornkjaer, Katherine formed a collective whose output includes, but is not limited to, digital animation, sculpture, film scores, illustration, and in 2019 an EP titled Voyeur. Accepting who she is and embracing the darkness has allowed all this to happen.

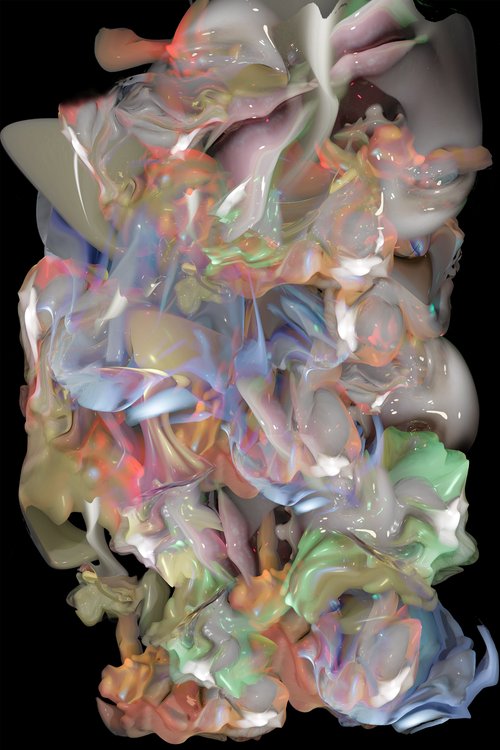

I came to O Future through their 3D art: technicolour, fatty, elastic, wet. 21st century Ubu characters rendered by someone with a Francis Bacon obsession and a computer. They’re fucking weird and exciting. The first thing that came to mind upon seeing these 3D pieces was the kinetic, plastic hyperpop sound of the late producer Sophie. Later, finding out that O Future also made sounds of their own felt entirely logical. ‘We like to make a total work of art. A total world,’ Katherine says. This world is undeniably cinematic, but not like any kind of cinema I’ve seen. I want to know what kind of mind makes work like this. Or rather, what kind of child grows up to be an adult that makes work like this. It’s a question which makes Katherine laugh, because, she says, when she looks at what she’s made she does see so much of her younger self in it. As a kid she spent ten years in speech therapy, was terribly shy, had undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome, and her absolute favourite activity was just to lie down and think. She read Dostoevsky and Nabokov aged 12, and hired six movies per weekend to watch on her own, followed by a further four to watch with her dad. High brow as it all sounds, there was always a tension there. ‘I grew up in a place that had no good taste. [South Africa] has all this trauma of apartheid, but also aesthetically apartheid was UGLY… Now I don’t like things that are too good taste. Stuff that’s too nice or cool. I like things with a bit of crunch. A bit of narrative.’ Everything must, she says, have a feeling.

Her ultimate idols are [in her words] ‘old school men’, and her objective is to achieve the warm, luminescent qualities of oil painting. She describes herself, and I love this, as ‘a truffle pig’. The truffle is, I think, the form of the thing. A song, a drawing, Katherine is agnostic when it comes to medium of expression. But the truffle could also be the countless influences which go into the making of the thing. She sprinkles her conversation with references, sometimes out of the blue –– we’ll be talking about one thing and then Katherine will say ‘Brecht’, and then move on quickly to another thought. John Waters, Hilma af Kint, David Mitchell, Turner, Edward Povey, Andrew Wyeth, Russian icon painting, 13th century Chinese ink painting, ballet, bebop, Soviet-era aesthetics. It’s all fair game. ‘Jens and I are futurists, but we are also, deeply, deeply classicists,’ she says. ‘We are always trying to make something new. We get very bored.’ Even their name is born of this push and pull. ‘I had this idea; imagine you were a peasant in the eleventh century, in a field, and you looked up into the sky and you stood up and lamented out loud “O Future!”. It’s a lament. A screech.’

I wonder aloud what a mealtime between the husband and wife must sound like, just an average night. ‘It’s not cool, crystal table, high brow all the time,’ Katherine says. ‘I like eating the same thing each day at the same time, and Jens is fine that he gets the same slop every night.’ They watch vast amounts of British panel shows; Mock the Week, Would I Lie to You, 8 Out of 10 Cats, Frankie Boyle’s New World Order, all Channel 4’s Big Fat Quizzes. It’s more of a linguistic fascination than a taste for political satire. ‘The Danes are great, they’ve got everything under the sun. They’re tall, they’re blonde, they tan –– I don’t know how, no one has explained this –– they have healthcare, they’re progressive, they’re feminist. But they don’t have lots of words. It is a cup. It is the sky. They have one word for one thing. So Jens is very impressed by the Anglo way… I love to watch him watch it, stop it and ask me to unpack the language for him.’ I’ll admit that I was surprised to be told I had a couple of Stephen Fry mega-fans on my hands, it seems so at odds with their aesthetic sensibilities, but I suppose there is a strange kinship in that autodidactic, multi-media, interdisciplinary, curious collectors of knowledge thing they’ve got going on.

It’s evident that Katherine’s recent Asperger’s diagnosis has helped clarify a lot of things for her. She is high-functioning, an engaged and captivating conversationalist, makes great eye contact even over Zoom. All this plus her distinct lack of mathematical aptitude made her believe that a diagnosis was unlikely. But there it was, and it explained a lot. ‘I am obsessed with the face. I see faces in shapes first, the distance [between the eyes] first, then shape planes. Not in a Minority Report way, but I see shapes. I’m continually trying to make a face.’ The diagnosis helped to contextualise this preoccupation, and helped explain why everything she does has a textual component, why even if she doesn’t know what something she has made is, she could retroactively write a whole essay about it. It has explained the disconnect between the way she sees the work and the way other people have seen it [even complimentary fans; O Future’s work has been described as ‘menacing’, a characterisation which Katherine does not identify with, although she does concede that there is a darkness to it]. Why she is so able to acquire new and challenging technical skills, allowing her artistic practice that exciting multidisciplinary approach. Why, having spent her whole life in training to become an actor, in order to be somebody else rather than the person she really is, the act of making became an inevitability, and choosing to sit inside that dark room made more sense than being outside with the palm trees and the beaches and the mountains of Los Angeles, bathed in sunlight.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?