Read Time 10 minutes

Disappearing ink

Tattooist Sean Prendergast delves into the mutually beneficial relationship between tattoos and photography: explaining how advanced photographic techniques can enhance the appearance of ink, and, in return, how tattoos can imbue an image with new layers of meaning.

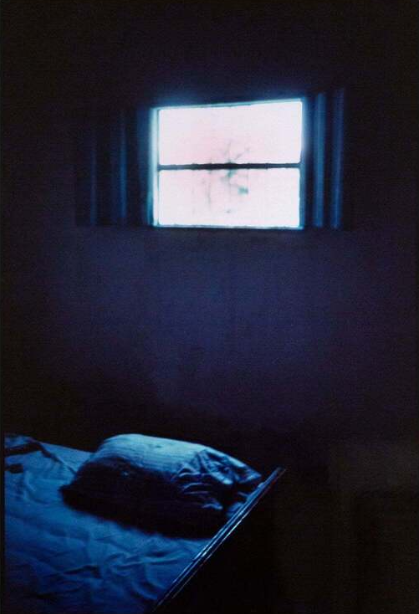

A few years back, I had an authentic Victorian-style photograph taken of my partner and I. We thought it would be a nice souvenir and something a bit different. Gregg McNeill, the owner of Darkbox Images, who took the photograph, encouraged us to watch the image develop whilst talking us through the process of wet collodion film. Whilst all that was fascinating, what really struck me was my tattoos … or, rather, lack thereof. Almost all of my tattoos had disappeared, yes, all 30+ of them, and those which hadn’t were severely faded, or appeared as nebulous shapes with no real determining features. My mum was thrilled.

There are some tattoo artists who see photographing their pieces as just a documentation of their work––a visual sales pitch––but to really push the art forward and achieve the best possible results, you need to see that camera as another piece of the artistic process.

There are many debates today within the tattoo community on whether or not photos should be edited. Should an artist show their work in the rawest forms, or is the lens so unreliable anyway that an artist is entitled to do some PhotoShop magic? It’s ironic that the community is so invested in whether or not we should PhotoShop our work, when we’ve done manipulation in some form or other since the invention of the camera.

It was the revelation of the disappearing tattoos in Gregg’s darkroom that started this research. Gregg took his first wet plate class in 2014 and started practising tintype photography in a professional capacity three years later. It’s a technique which was invented by the Victorians, circa 1851, but by the 1930s had been largely phased out with the introduction of panchromatic film. The processing of this type of photo is very susceptible to the blue/green end of the ultraviolet spectrum, which, for Victorian tattoo-wearers, meant their body art appeared much lighter in print. Due to the inks used and the erasure of the natural blue in skin tone, the skin in these photographs appeared darker, closing the contrast between the layers and blurring the readability.

This creates a problem when photographing tattoos, especially on people with an already darker skin tone. Maori tattooing, almost more than any other type, is story based. Each design, every tooth and concentric circle, each band directly translates to an event in that person’s life – their achievements and their social status shown beneath their skin. Wet collodion subdued all of that too, whether intentional or not the documentation tool of the photo served to erase history rather than preserve it. Without early manipulative post-production these records would be lost.

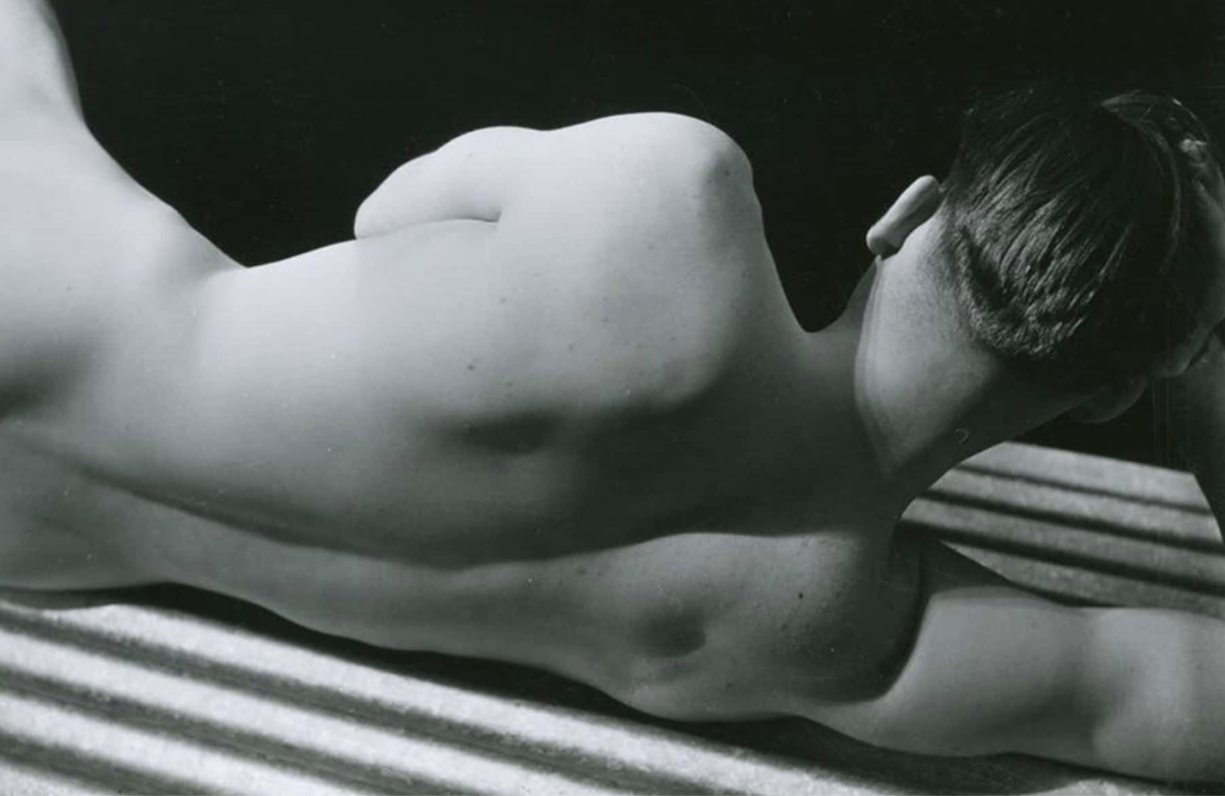

And in the Western tattoo world? Ben Cordray, a tattoo artist who was prolific in the 1920s and whose work was foundational to modern versions of the practise, produced a series of tattooed nudes, where at least one photo was used several times as a kind of template, each time displaying different tattoos. We know that these photos were edited – even then. The artist physically drew the tattoo onto the processed wet plate in order to showcase his work, a common photo manipulation technique of the pre-digital era. If we look at more of Cordray’s work we can see the faint scratches in the designs, something present in the photo but not present in any of the preserved tattoos. In some instances the skin behind the tattoos looks ethereal, so bright that any form of skin and natural shadowing has been completely erased. Other photos from the era contain flat tattoos on rounded surfaces.

Even a contemporary tattoo; take a photo of it and apply a graphite or monochromatic filter and the piece will look darker and more consistent, as the slight blue undertone is filtered out. We can apply this logic to the tattoo photography of Cordray’s era and see that the representations don’t match, the colour palettes don’t sit the same, especially so when you consider inks from over 100 years ago had a lot more of that blue present. This is why your da’s tattoo healed a blueish grey.

Modern tattooists are fearful of photo editing, worried that it is tantamount to false advertising. You see a vivid tattoo on the artists’ Instagram and you expect similar results without realising that a great tattoo photo is similar in its artifice to great food photography; removing a red undertone or muting the background is really no different than using PVA glue to synthesise that perfect cheese pizza melt, and nothing makes a coffee look as appetising as washing up liquid [but you wouldn’t really want to drink it]. It’s not the everyday experience, it’s the aesthetic peak, and isn’t that what we want to achieve in an advert? Often a style like blackwork will be heavily edited, due to the ease of simply throwing on an Instagram filter to make it appear more consistent across the colouring.

As you can imagine, there is a lot of localised trauma on the body during the tattooing process and, as with any trauma, the body reacts. This can be through swelling and distortion, but it always involves redness, and, anyone with even the most casual understanding of colour theory will comprehend the way that undertone will alter the shade of every ink placed above that. Likewise, a bright coloured tattoo [check out an artist like Sean Newman to see just how incredible this can look] is going to look fantastic on pale skin but might not be as dazzling on someone with a more pigmented skin tone, but contrast that––see what I did there?!––with an artist like Miryam Lupini, who creates these wonderful tattoos on darker skin through the use of pastel inks, and you’ll see how integral colour theory is to the process. Once you understand the tone range of the skin and the canvas you’re working with you can ensure your ink gives a strong contrast, making that tattoo last longer and stand out better.

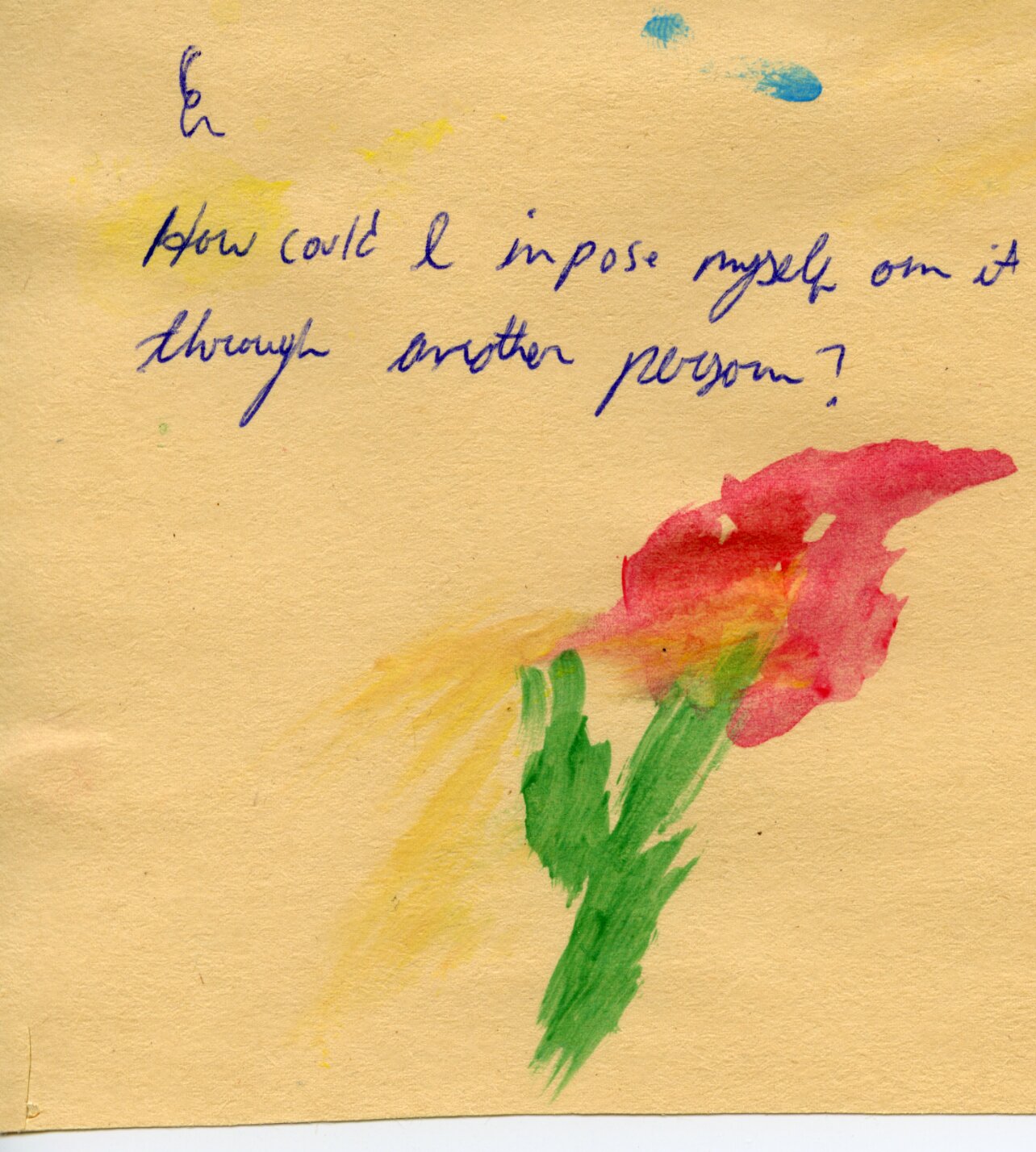

Tattoo lovers need to make friends with the camera and understand its possibilities in order to get the best results in showcasing their own art form. But what about the photographers who take pictures featuring tattoos? Beyond the technical, the tattoo’s cultural significance and emotional impact can contribute to the narrative of the photograph itself.

A great example of this would be the work of Diane Arbus, in particular her work with American, mid-century carnival workers.

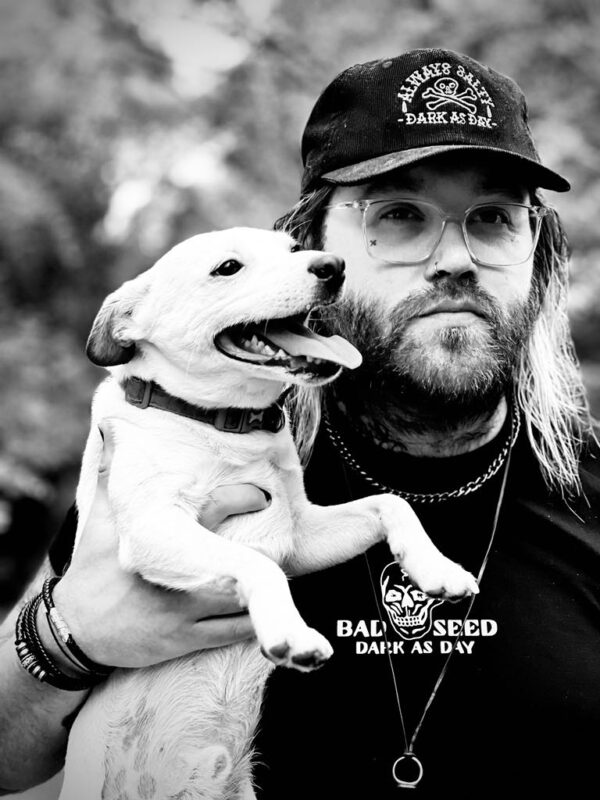

I look at these photos and I feel sad. The subject isn’t sad but the photos capture a full story. Tattooed man at a carnival [c.1970] has a look of pride and wonder, I honestly feel like this is the first time he’s not felt objectified or ostracised over his tattoos, and the exotic, for once, feels normal. The grain of the photo captures every last hair and wrinkle whilst muting his tattoos and I feel seen. I can project myself onto that subject and remember that underneath this colourful canvas of skin I’m just a guy. A guy with fears, wants and desires. Tattoos have long provoked an unwelcome kind of judgement, created in their wearer an edgy, even dangerous anti-social stereotype, but being understood through the lens of a fine art photographer has helped bring them to life, to be recognised as beautiful.

Whilst Arbus’s work is bittersweet, you could say the opposite of Jake Verzova, his work in Manila and his 2014 publication The last tattooed women of Kalinga. The tattooed subjects silently tell the story of colonial resistance. The women are covered in symbols of pride and accomplishment, an ancient tradition of the tribe that has stood the test of time and weathered the creeping storm of Westernisation. In this series, the Kalinga women read as resigned to the progression of the world and their confinements to its history. Looking at his work you feel like the world has moved on and these women are living ghosts.

Whether you ascribe to the theory that tattoos have a secret language or not, the facts that they physically exist on the human body, and that they are, largely, permanent additions, renders them uniquely evocative. At varying points in the last 300 years, tattoos have been synonymous with savagery, Orientalism and the ‘exotic’ East, the working class, the prison industrial complex, sideshow spectacles and even nobility. Today we see tattoos in contemporary marketing and it evokes a certain message around subcultures: this person is cool, this person DGAF.

There is something unique in the art of photography that allows it to marry up perfectly with the art of tattooing. Both art forms require a knowledge of the body, many a great tattoo has been ruined by not understanding this. The placement of the tattoo is too far in some direction, distorted or hidden by the natural pose of the body, the curve and bend of musculature or the flexing of veins. Both are so important in telling a story and to truly capture movement in such a static form – like catching lightning in a bottle. More than just being a documentary tool, the two mediums can marry to enhance and improve the other, and come together to create powerful stories.

END

subscribe for the latest artist interviews,

historical heronies, or images that made me.

what are you in the mood for?